Children born in East Oakland, California have a life expectancy 12 years lower than those born in Piedmont, California. Oakland Unified School District reports about 1,600 homeless students, whereas Piedmont High reports zero. Residents of Oakland have a median household income of $51,000. In Piedmont, it is over $130,000. Yet less than two miles separate these cities. How can two areas so close together have such stark disparities? On the surface, Alameda County, home to both Oakland and Piedmont, seems like one of the most prosperous counties in the country. But when you dig deeper, something more sinister emerges. African American and Latino people make up about 28 and 25 percent of Oakland’s population, respectively, while 34 percent of the population is white. On the other hand, white people in Piedmont consist of over 74 percent of the population, whereas less than six percent of Piedmont’s residents are Black or Latino. Similar disparities exist all across the Bay Area, not just in Alameda County. A history of discriminatory policies and attitudes has resulted in severe segregation in the Bay Area, trapping African Americans and other racial minorities in cycles of poverty that are almost impossible to escape from.

The Bay Area is full of long-haired hippies smoking their newly-legalized weed, so many assume segregation could not a problem in such a liberal place. Well, not quite. The San Francisco Bay Area, along with the rest of the country, has a long history of discriminatory housing policies. Richard Rothstein notes in his book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, the Bay Area experienced a huge influx of shipyard and industrial war workers, many of whom were African American, during World War II. This massive wave of migration increased the black population of Richmond from 270 to 14,000 people. However, Rothstein also stresses that housing development in the area failed to keep pace with population growth.

The federal government attempted to provide assistance with public housing, but really just worsened the situation. Clear disparities in the quantity and quality of housing existed along racial lines. African Americans received poorly constructed buildings near the water and railroad tracks, while white workers resided in structurally sound houses in white neighborhoods. To make matters worse, the government actually encouraged private groups to segregate the Bay Area. Local governments urged bankers to offer loans to the middle- and upper-class, but not to those buying in poor, non-white neighborhoods. Additionally, the Federal Housing Administration would not insure loans for construction costs if the developments were intended for African Americans or for whites moving into African American neighborhoods, according to Rothstein.

Government policy protected white residents by preventing African Americans and other minorities from “infiltrating” their precious neighborhoods. And neither public nor private groups even attempted to hide their blatant racism. In fact, they inflamed fears of a “Negro invasion,” furthering their goals of segregation. Government policies and private attitudes concentrated African Americans in certain cities and neighborhoods across the Bay Area. These divisions persist today and continue to disadvantage the Black population in more ways than mere access to housing.

Segregation and entrenched racism still plague the Bay Area. This forges a cycle of poverty for the people of color living in and migrating to the region. The people forced into these cities and neighborhoods face higher unemployment and greater economic distress. Additionally, their children receive worse educations. These factors combined perpetuate a vicious cycle and contribute to segregation itself.

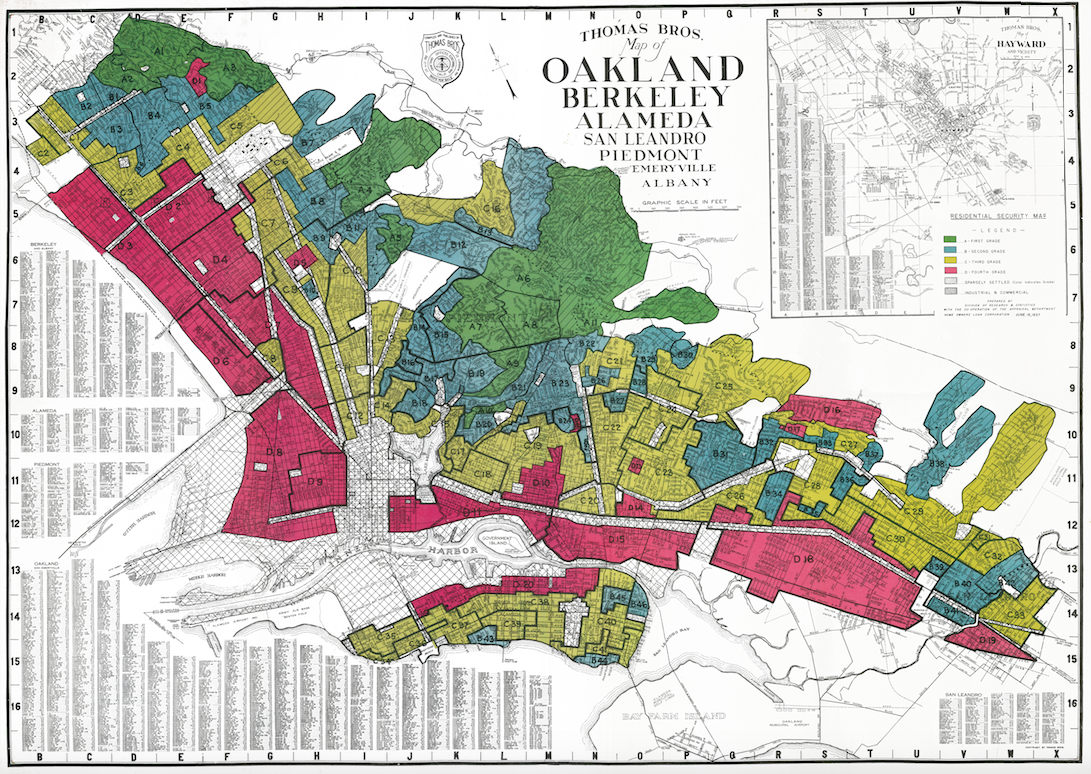

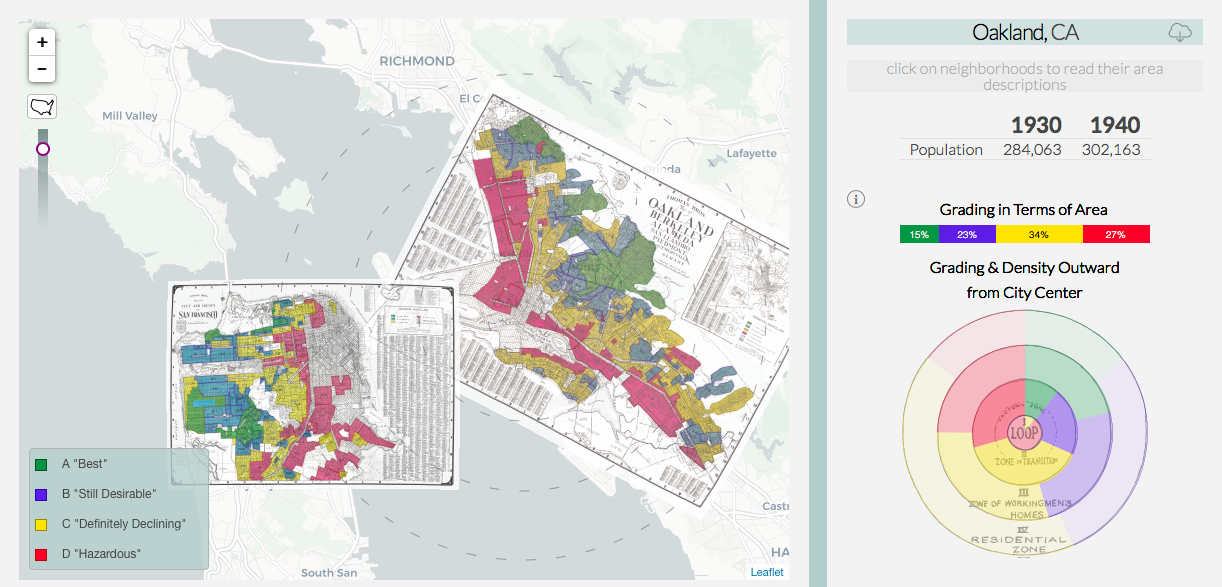

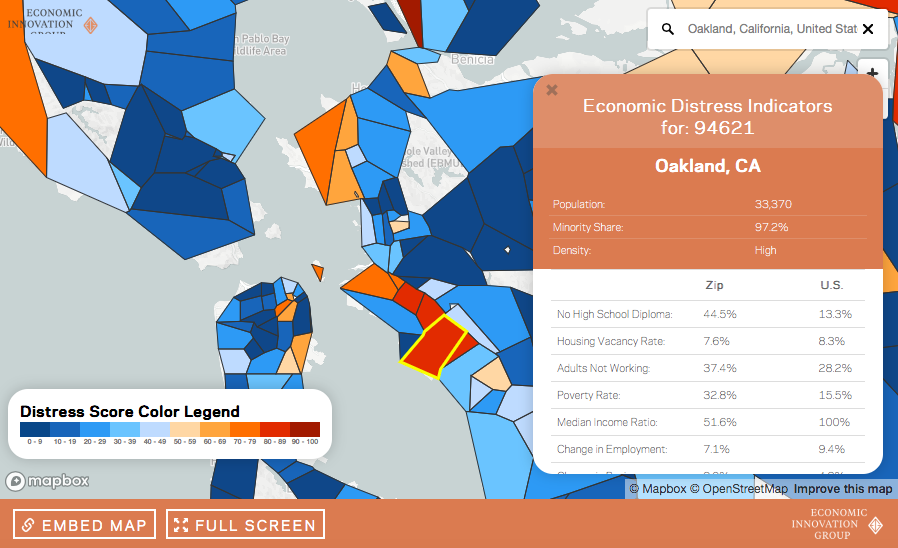

The above map of Oakland and Berkeley reveals distinct areas of distress and segregation. Strikingly, the zip codes facing the most economic anguish align closely with those that were deemed “hazardous” or “definitely declining” through redlining processes in the 1930s and 40s (if it was not clear, “hazardous” and “definitely declining” meant high or increasing numbers of minority residents). San Francisco rests comfortably among the top 10 most prosperous cities in the United States. On the other hand, Oakland and a handful of other Bay Area cities struggle to keep their heads above water as a result of historical and continued patterns of segregation. These divisions have permeated beyond housing guidelines to areas such as education.

Wealthier, whiter people have entrenched segregation and the cycle of poverty by encouraging policies that ensure their children go to schools with greater resources and larger percentages of white students. In the United States, residents pay housing taxes to help fund K-12 education in their school district. In turn, school districts with a higher percentage of low-income families receive fewer resources to provide an education for their children than those in wealthier school districts. The low-income districts just so happen to be those with larger African American and Latino populations, as people of color are disproportionately poor.

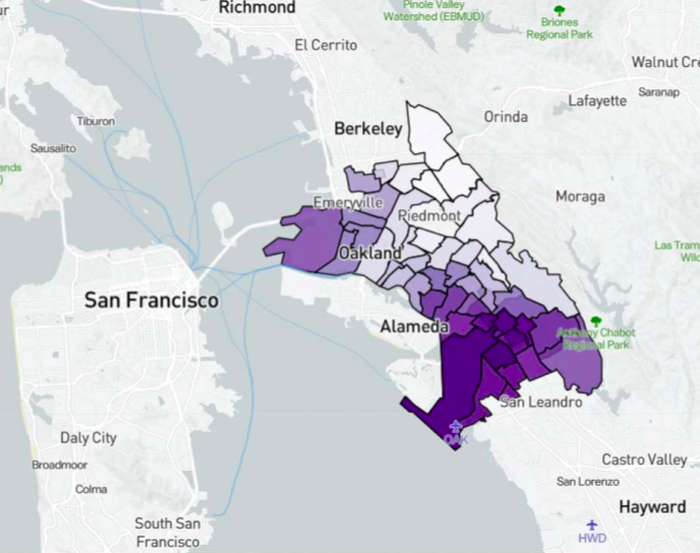

This map draws attention to the stark segregation that exists among school districts (the darker the purple, the higher the percentage of Black or Hispanic students). Again, these divisions do not stray much from those of housing discrimination in the mid-20th century or from the areas suffering greater economic distress today. And this is not an accident. Those with political clout, or the whiter, wealthier residents of the Bay Area, have pushed policies that benefit themselves and their children, but hurt low-income and minority communities. The school districts with larger African American and Latino populations obtain fewer resources to educate their students. Thus, people of color graduate at lower rates than their white counterparts. Further demonstrating the divisions, merely 64.9 percent of students in Oakland, which has a higher percentage of students of color, graduated in 2017. So, not only are these disparities constructed by discriminatory policies, but they contribute to the perpetuation of segregation in the Bay Area, as well.

Funneling people of color into this cycle of poverty also reduces their chances of receiving a college degree. Wealthier people receive much greater access to higher education. For example, 17.5 percent of Stanford’s student population comes from the top 1 percent of income earners, whereas only 18.6 percent comes from the bottom 60. (UC Berkeley, on the other hand, has less than 4 percent from the top 1 percent and more than 29 percent from the bottom 60.) And while many colleges have rendered their universities affordable, especially elite private schools as they can offer generous financial aid, they fail to meaningfully increase access to low-income students. Even if higher education suddenly becomes affordable, lower-income, and thus minority, students do not receive offers as frequently as richer students. And a fancy financial aid package is not worth much if not one can take advantage of it. Additionally, even when lower-income students are just as high-achieving as richer students, they are less likely to apply to selective colleges. As a result, less than half of the bottom fifth of American families attend any university at all, thereby perpetuating segregation and continuing the cycle of poverty. A college degree can create a world opportunities for upward mobility. However, African American and Latino students do not receive equal access to universities, thereby diminishing their chances of breaking free of the cycle. As a result, most students who grow up poor remain poor, and those who grew up wealthy remain wealthy. Thus, segregation in the United States, and the Bay Area trickles from housing discrimination, into K-12 education, and all the way up to higher education.

Those with a college degree often migrate to denser cities, like those in the Bay Area, once they graduate, thereby contributing to segregation. Less than one percent of people with less than a high school diploma, and just over 1 percent of those with solely a high school diploma, leave their communities. On the other hand, individuals who receive a higher education migrate twice as often as those who do not. Thus, wealthier, whiter individuals migrate at a much higher rate. The Bay Area attracts this top talent, as it offers an array of high-paying jobs and an exciting culture. In turn, the region had a positive net migration rate of young college graduates between 2000 and 2015. In fact, over 40 percent of the population in most Bay Area counties now have Bachelor’s degrees. Yet when these young, educated people move to the Bay Area, they often do not choose to live in the areas with the highest poverty rates or the worst crime. And when they do, those neighborhoods quickly become gentrified, thereby forcing the low-income residents into even more distressed areas.

The Bay Area, along with the rest of the nation, struggles with severe segregation. African Americans, and other minorities, clearly suffer disproportionately, but the rest of the Bay Area suffers as well. The distance created sparks increased racial polarization, as well as political and social conflict. As Rothstein notes, this polarization enables corruption. Politicians can inflame whites’ sense of racial entitlement and gain support for policies that perpetuate segregation. As we have seen more recently, political leaders or candidates can mobilize white voters who have been “disenfranchised” by attempts to level the playing field; and the results of this certainly hurt everyone in the Bay Area. (Take the war between Jerry Brown and Donald Trump, for example.) Additionally, racial segregation harms both the distribution of national wealth as well as the generation of that wealth, according to Rothstein. Social psychologists found that whites gain a false sense of their own superiority due to racial separation. As a result, they perform worse and do not feel the need to challenge themselves. More diversity on teams, Rothstein points out, can actually heighten creativity and reduce the number of errors. Thus, decreasing segregation increases productivity and innovation, which benefits everyone. So Google, it might be worthwhile to increase the number of African Americans in your workforce to more than two percent. Eliminating segregation, which policy has deeply entrenched in society, will take more than just a change in attitude. Numerous organizations and people are working towards ending housing discrimination every day, and achieving this goal would have widespread, positive impacts for everyone in the Bay Area.

Featured Image Source: 7X7

Be First to Comment