Michael Hamill rose and fell over six years, then three days. This rise and fall, and the ethics thereof, provides a challenging case for exploring the limits of public and private life, and the dissolving barrier there-between. It also raises important questions that ought to be, and I would argue in fact need to be, interrogated regarding mob justice in the digital age.

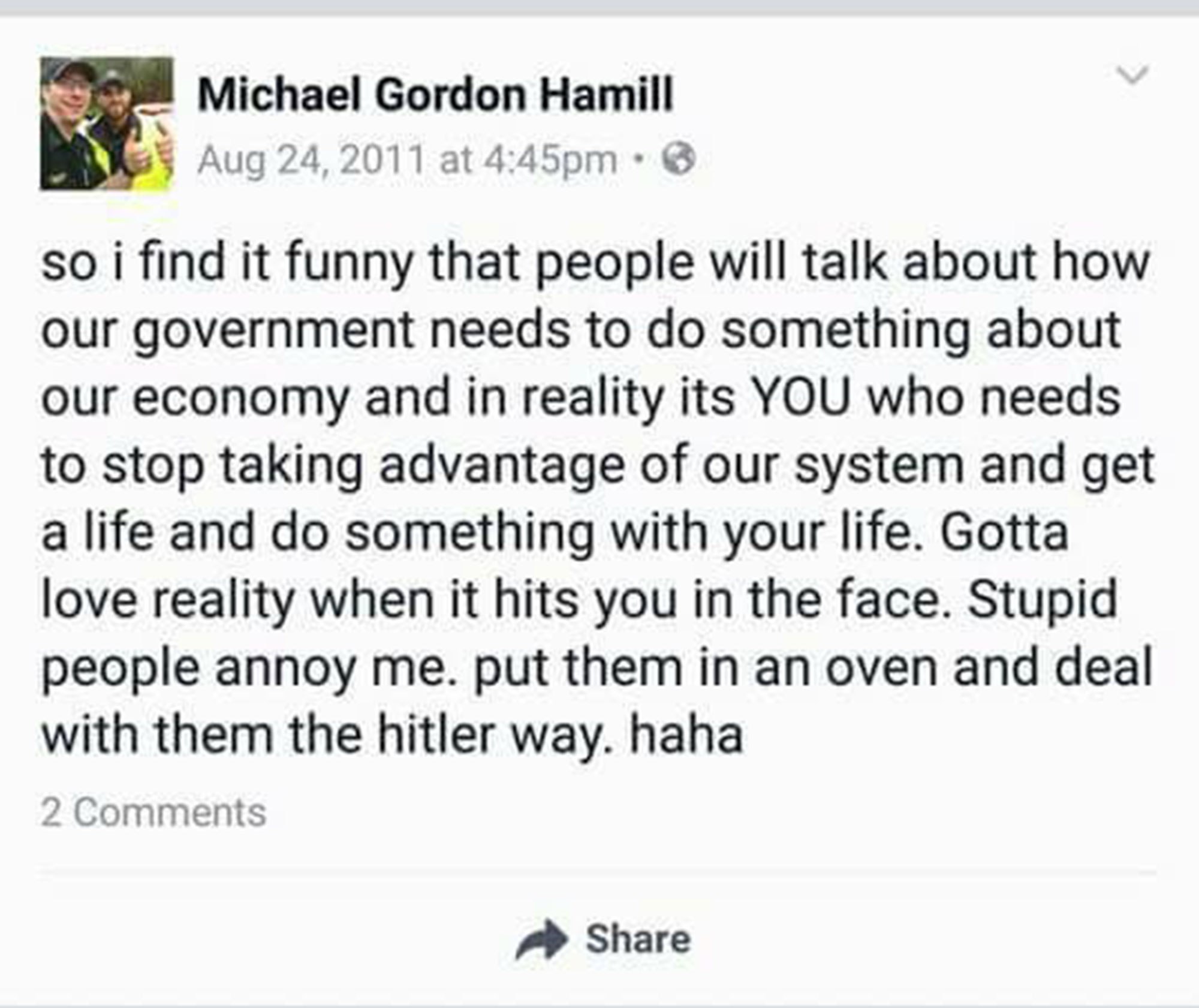

Hamill’s story begins with an attractive selfie posted on Sept. 10, which depicted Hamill aiding in Irma recovery operations, shown above. It’s a flattering picture that rendered Hamill perfect for rabid attention. Unfortunately for him, however, this attention brought scrutiny when it resulted in two anti-Semitic Facebook posts referencing the Holocaust from four and six years ago emerging. The exposure of these posts, and ensuing complaints regarding said posts, subsequently resulted in Hamill’ suspension pending investigation into the matter.

Was it right for Michael Hamill to be exposed for Anti-Semitism? Was it right that this exposure then resulted in his firing from the City of Gainesville’s police force?

The answer to the first question seems, at first glance, to be an obvious and resounding “yes.” There is an obvious moral case for removing Hamill from the force: anti-Semitic racism, and racism wholesale, are impermissible, and it should be made abundantly clear wherever this behavior pops up that neither are to be tolerated. Still, there are details that complicate a moral justification: these posts are older than Hamill’s tenure in the police force and are distanced from Hamill now by as much as a fifth of his life. What’s more, they were presumably made with the expectation of semi-privacy: they were made on a personal Facebook page.

Considering the case through a more abstracted lens, I feel, makes the case less clear-cut; an individual is sexualized while working, that sexualization results in mass-popularity as a meme, and one particularly curious observer pries into said individual’s digital footprint to find reprehensible behavior from over half a decade ago. That reprehensible behavior, without further context, is brought to light and results in the mass-shaming of the individual in question by a seething mob of far-removed spectators and soapboxers, and the dismission of this individual. We as the participant-audience then get to feel good for having taught the individual a lesson and for having issued their sentence for the crime, as judge, jury, and executioner.

This abstraction does not excuse Hamill, but it allows for interrogation of the ethics of the shaming itself. Suppose, in the past six years, Hamill was made to see the error of his reprehensible belief. Suppose in the six years that have passed between that post and now, he was made to improve himself (as one would hope he certainly would). Suppose that he gets a new job and turns his life around, and the anger and confusion and general vitriol that no doubt inspired that post was removed from Hamill’s corporeal being. This hypothetical improvement is all lost in the public shaming. What is out cannot be removed. The public cannot unknow Hamill as an anti-Semite. His face is irreparably associated with the evil on those posts, and any room for improvement of the self is extinguished.

This is not to excuse Hamill, though; he could well be a racist and a bad person. We simply cannot know, however, because the second he is outed it doesn’t matter what the truth is: the truth was presumed and acted upon, and the punishment was doled out.

This sort of mob justice — sentencing and punishment by seething internet-armies — is not unique. One might remember Justine Sacco’s life imploding after a poor-taste, horribly offensive joke made her a target to retweet-retribution. In both cases there ought to have been a semi-expectation of privacy, though the two are not equivalent cases: in one, a woman’s life was torn apart because she had no adequate platform by which to explain what, by her account, was a mistake initially intended to be viewed by a handful of people. In another, no explanation has been offered nor is possible for the unveiling of an antiquated offense. In both cases, however, prosecution was carried out without the possibility of defense on the presumption of some evil.

Abstraction complicates the moral case: do these two cherry-picked posts reflect Hamill today and warrant the public debasement he’s now receiving? One could convincingly argue either way, leaving no certain answer to the question of whether or not Michael Hamlin’s shaming, and his ensuing suspension, was an ethical course of action. There is, however, another reading that ought to be considered regarding the suspension consequent to this shaming, distinct of the ethics of the shaming itself, which can inform one’s opinion. For this, one must interpret the interaction between a cop and his or her policed body of people as a collaborative production; an economic interaction. For this reading especially, I turn to the work of Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter in his work The Strength of Weak Ties.

In theory, both the police and their policed bodies can be read as firms that cooperate with one another in creating a product: harmonious society. Under this reading, police officers should serve in a metaphorically productive capacity, “shaping” society. The communities they serve provide the raw-material “society” to be shaped. Efficient interactions between these firms necessitates a great deal of trust (Granovetter, 1992, 58-61). Police cannot effectively “shape” society if that society does not trust the police to fairly and effectively do so. What’s more, this trust is necessary “not only at the top levels… but at all levels where transactions must take place” (Granovetter, 1992, 66): this is a semi-articulation of Granovetter’s overarching argument of “embeddedness”: rational action does not exist in some plane separate of preexisting social ties, and individuals do not merely “forget” social interaction when it comes to marketized interaction. In light of embeddedness, all constituent police officers within the institution of “The Police” therefore have a burden to uphold a façade of trustworthiness: the embedded social ties between the police and their policed-body allow for more efficacious policing so long as it remains positive.

Hamill’s public shaming introduces friction. How can a policed body trust police who are demonstrably racist? A Jewish individual cannot meaningfully trust an anti-Semite. Had these posts remained hidden, perhaps this friction would’ve never come about, but their public exposure forces the City of Gainesville’s hand. In order to efficiently police, the friction must be removed.

This is a flawless example of negative-embeddedness: the social interaction of the racist with those who find racism unpalatable prevents even “rational” interaction. In a Granovetterian reading, Hamill needed to be suspended, irrefutably. To keep him on without acknowledging the unfortunate externality of his racist posting-past would be to keep friction that burdens the production of harmonious society. Thus, regardless of the ethics of publicizing Hamill’s past, once his private life was made public, Hamill’s fate was sealed.

So one can return to the question; was this ethical? I earnestly believe – and this is in no way to defend an anti-Semite — that the ethics of the public shaming are questionable at best, and evocative of mob-justice vigilantism at worst. I do believe, however, that the firing of Michael Hamill was not only ethical but in fact was a necessity. The police as a body ought to protect those populations who cannot protect themselves from incursions upon their rights, and that includes the same minority groups that Michael Hamill saw fit to target four and six years ago. This irony has real consequences on the trust that is required for meaningful interaction between police and their policed bodies. What we must now ask is not whether or not this sequence of events was ethical, but whether or not the whole ethos of mob-justice endemic to social media is ethical. To that question, I think the answer is “no,” and we ought to spend more time interrogating ourselves before we deem ourselves appropriate jurors in public opinion cases such as that which decided Michael Hamill’s fate.

Featured Image Source: People Magazine, by way of Michael Hamill’s Facebook page.

Be First to Comment