Housing on the site of People’s Park won’t be coming anytime soon.

That’s what campus spokesperson Dan Mogulof seemed to suggest after the First District Court of Appeals handed down its verdict in Make U.C. A Good Neighbor v. Regents of the University of California. The Court held that the University’s Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the proposed housing project at People’s Park was insufficient. The University will have to return to square one and develop a new EIR that analyzes alternative project sites and addresses potential noise stemming from the new development.

While People’s Park advocacy groups rejoiced, many pro-housing voices critiqued the decision. Governor Gavin Newsom released an impassioned statement, asserting that “our CEQA process is clearly broken,” and “California cannot afford to be held hostage by NIMBYS who weaponize CEQA to block student and affordable housing.” Newsom has staked his political success, both locally and nationally, on ending the housing crisis in California, so the governor’s outrage shouldn’t be surprising. Editorial boards, politicians, and business leaders are all calling for an overhaul of CEQA. Others are a bit hesitant to strip down one of the most significant environmental laws in California’s history.

What is CEQA?

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), signed in 1970 by President Ronald Reagan, is probably California’s most significant environmental law. Modeled after the Federal National Environmental Policy Act, CEQA aims to ensure transparency of the impact of new development on humans and natural systems. It requires state agencies (in this case, the University of California) to disclose and evaluate the significant environmental impacts of a project. Many environmental groups claim that CEQA promotes environmental justice and mitigates the adverse effects of new development on historically marginalized groups. Jonathan Pruitt, the Green Zones program manager at the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA), emphasized that CEQA makes governments “stop and think.” Others assert that CEQA creates too many hurdles to new development and has been weaponized by wealthy interest groups.

CEQA: A Tool for Good

It’s easy to point out flaws in any piece of legislation. Criminals are able to attain guns in the face of gun control laws, millionaires can find loopholes in the tax code, and corporations are able to evade giving their employees fair overtime pay. However, these failures do not mean a statute should be overturned. Let’s take a look at a few development projects and how the CEQA process mitigated the impacts of development.

In 2017, the City of Sacramento announced plans to build a massive extension to the University of California, Davis campus. Coined “Aggie Square,” the new development encompasses about two dozen acres and includes two brand new labs, a 53,000-square-foot hospital, and 285 multifamily housing units.

Concerned about potential gentrification and the well-being of existing residents, the interest group Sacramento Investment Without Displacement (SIWD) filed a CEQA lawsuit against the city. Through the CEQA process, local residents engaged in community meetings and negotiations with local officials. In 2021, Mayor Darryl Steinberg announced that SWID and the City of Sacramento had signed an agreement. SWID received major concessions for dropping its lawsuit, including $50 million in funding for affordable housing in the project area, hiring preferences for local residents, and improved transportation options (walking and biking corridors) that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

CEQA made these compromises possible. Pruitt contends the CEQA process allowed stakeholders to identify opportunities for local hire and affordable housing. Without CEQA, the City of Sacramento could have ignored public concerns and continued development as previously planned. In the long run, the agreement will benefit all stakeholders—promoting technological investment and research while providing quality jobs to Sacramento residents.

Analogously, in South Fresno, California, Amazon planned to expand its facility to 420,000 square feet. South Fresno residents, who are primarily low-income people of color, again used CEQA to extract concessions from Amazon, including a community benefit fund to alleviate the effects of increased air and water pollution, third-party air quality monitoring, and a study on increased traffic resulting from the expansion.

Even the most ardent CEQA defender wouldn’t contend that California should stop all development. However, CEQA allows California residents to speak with developers directly, center community priorities, and protect marginalized communities. Maybe the People’s Park case is a blatant distortion of the intent of CEQA. But throwing the baby out with the bath water would be just as bad, if not worse.

How Realistic is CEQA Reform?

CEQA is a product of the California legislature, so if they view the Court’s interpretation of CEQA unfavorably, they can tweak the law. In fact, the legislature has carved out pretty significant exceptions to CEQA already. Last year, after a California Supreme Court ruling that mandated U.C. Berkeley cut its fall 2022 admissions by one-third, the legislature amended the text of CEQA. Senate Bill 118 “removed campus enrollment as a ‘project’ in the eyes of the environmental law,” and allowed the campus to admit all accepted applicants as planned. Additionally, lawmakers have repeatedly made CEQA exceptions for the construction of new sports stadiums in the state, such as Golden One Center in Sacramento (2013) and Chase Center in San Francisco (2015).

For all the big talk, it’s unlikely Governor Newsom wants a massive political battle with labor unions and environmental groups during his last three years in office. It’s no secret Newsom has presidential ambitions, and he can hardly afford the political mess that overhauling CEQA would precipitate. Democrats will probably end up pushing through a specific CEQA exemption for the People’s Park project in lieu of gutting CEQA completely. Pruit hopes that if Newsom is serious about reform, he allows environmental justice communities to “have a seat at the table” and not fast-track reform.

Democrats will have to get creative. Preventing student enrollment from being considered a project is one thing, but claiming a 17-story housing development isn’t worthy of an EIR might be politically challenging.

People’s Park

So where does that leave the People’s Park development project? Certainly, many Cal students couldn’t care less about CEQA, but they would enjoy not having to pay $1500 a month to live six blocks away from campus. As the Court noted in its decision, U.C. Berkeley provides housing for just 23% of its students. The statement from the University following the decision emphasized their commitment to the project was “unwavering.” Despite that, People’s Park defenders are resolved as ever to fight the development. Last August, when the University moved to begin construction at People’s Park in the dead of night, dozens of protestors ripped down barricades and forced a unit of police officers in riot gear to retreat from the park. The University halted construction at the site.

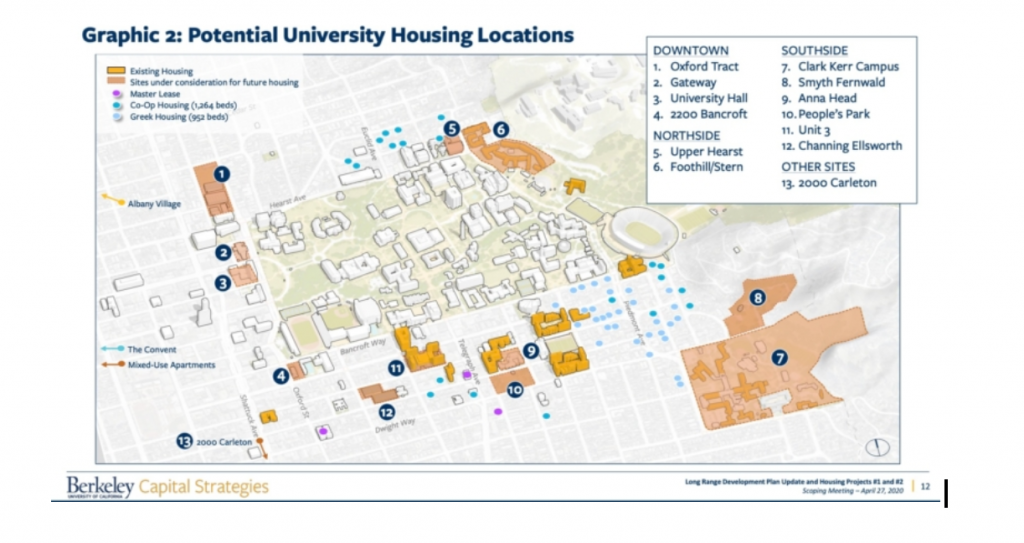

The Court mentions that U.C. Berkeley should have considered alternative sites for housing development. U.C. Berkeley has identified 13 potential sites.

Possible housing locations identified by University administration | Source: UC Berkeley Housing

While 13 potential sites seem like a lot, many of these sites already have housing on them. Anyone who has lived in Unit 3 or eaten at Cafe 3 knows that more housing on those sites would be nearly impossible. Although the sites on the Northside of campus could add more beds, most students want to live on Southside due to its proximity to campus and better social opportunities. Also, more housing on Northside would just transfer the noise issue to that side of campus. In sum, the People’s Park site is the most attractive site for a reason. It’s owned by the university, close to campus, and has no existing development. However, filing another EIR report and fighting another legal battle could take years. The University originally announced its plan to build on the People’s Park site 18 months ago, and it’s almost certain any construction will not begin on the site for at least another year and a half.

Looking Ahead

People’s Park will continue to be a contentious issue in Berkeley and California politics. A candidate’s views on development at the site will be a political litmus test for years to come. Every future mayor, councilmember, and University administrator will have to take a side and face the political consequences.

Furthermore, unless Governor Newsom achieves a political miracle, appellate Courts and the California Supreme Court will continue to issue unpopular CEQA rulings. Conflict over development is inherent to a state that prides itself on environmental protection and economic prowess. The rate at which California develops will be influenced by the outcome of these cases. CEQA remains the most powerful environmental law in the state, and every would-be developer should prepare for a rigorous CEQA challenge in the courts.

Featured Image Source: Berkeley Side

Comments are closed.