In 2018, a video of former President Barack Obama calling his successor Donald Trump a series of expletives gained traction online. While this was engineered by deep fake technology, a tool used to digitally alter a subject’s actions and speech, the public was widely ignorant of its origins. Consequently, the video circulated primarily through social media as a matter of concrete fact, as some people genuinely believed in the veracity of the product. The events of 2018 underscore the extent to which misinformation—perpetuating incorrect or misleading information without the intention to deceive—largely contributes to the ambiguity of truth.

As the world grapples with solutions to misinformation, particularly in the political realm, Brazil is facing a similar crisis. Leading up to the most recent presidential election that ended on October 30th, 2022, Supreme Court justice and election chief Alexandre de Moraes was unanimously given sole authority by seven federal judges of the electoral court to classify and order the removal of online content he deems to be misinformation about the election. Such unilateral authority exemplifies an extreme measure, regardless of where one’s views fall on the political spectrum. As the unwanted external influence of digital misinformation takes center stage and calls into question traditionally reliable political affairs, there must be a middle-ground solution to subdue the issue. Although Brazil’s iron-fisted legislation is unsustainable for modern democracies, there are principles global political bodies can draw and implement from its unprecedented methods.

The rise of misinformation as a thorn in politics’ side meant that attempted remedies were quick to follow. However, there are certainly discrepancies in how different countries handle misinformation. In China, Belarus, and France, misinformation is punishable by law, most often through media control and threats to revoke operating licenses for perpetrators of this perceived crime. As opposed to waving the stick, the United States has implemented a grassroots approach. California has recently started media literacy initiatives in schools to equip future generations with the intellectual capacity to filter out misinformation from their daily intake. Although the government plays a significant role in counteracting misinformation, technology companies— namely Twitter and Meta—that have monopolized communication and, by extension, the exchange of ideas have taken similar steps to minimize this issue on their platforms. The increasing burden on these companies to eradicate the majority of misleading content meant that policies have gotten more stringent, and more content is being classified as misinformation.

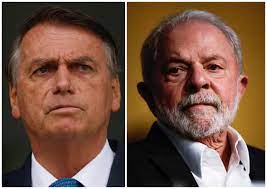

Following this trend, Justice Moraes has used his executive authority to fiddle with technology companies’ policies. Social networks deemed to have spread misinformation about Brazil’s election are being told, at the discretion of Justice Moraes, to take down such posts within two hours. Should they fail to comply, they risk no longer being permitted to operate their services within Brazilian territory. Posts accusing Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the left-leaning challenger to the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, of supporting men using public restrooms next to little girls have been taken down. Further, contrived comments about Bolsonaro confessing to pedophilia and cannibalism have faced the same consequences. Justice Moraes reasoned that these changes would address complaints of misinformation which have increased 17-fold compared to previous elections. However, the prospect of future dictatorial censorship looms large over Brazil’s politics. Especially given the fact that Justice Moraes has known political leanings as part of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSBD), it seems as though decisions may stray away from impartiality. Future election chiefs could exercise their rightful authority in the bounds of Brazilian law and use it to push their party’s agenda further while drowning out opposing views. Such powerful means of censorship have the possibility to sway high-profile elections and skew media narratives in one direction.

As such, Brazil’s current misinformation control tactics will taint the legitimacy of its political processes. Given that Brazil is emerging from an era of instability under its former President, Jair Bolsonaro, distrust of the government will only add unnecessary turmoil to its already fragile and transitioning state. In the long run, this distrust will develop into a disconnect between the government and its constituents, burning down remnants of the democratic process Brazil had.

However, despite its evident ethical quandary, other countries could learn from Brazil’s actions to combat misinformation. As the world watches Brazil’s unprecedented effort unfold, it could consider introducing certain mechanisms of the nation’s policies. First, having a regulatory body specifically dedicated to combating misinformation has merit. However, instead of conferring unilateral authority to a politically biased individual, employing a transparent and independent group of regulators could be beneficial. Selecting regulators could follow a similar structure to the United States Federal Election Commission: first appointed by the President, then confirmed by the legislature.

Additionally, requiring them to publish documentation on how they arrived at certain decisions or conclusions will help boost accountability. This way, there are more democratic components to misinformation control. Having multiple people participate in this process will foster discussion and ensure that multiple viewpoints of a case are explored. Just as judges are trained to rule strictly based on the law without the interference of personal political leanings, selected regulators can undergo a similar process to ensure their impartiality to the best possible extent. As a result, censorship rooted in political narratives will be diminished, and there will be no dominant party bias, taking care of the main issues presented in Brazil’s strategy.

Although Brazil has notably taken draconian measures to curb misinformation, it offers an avenue to test the waters of policies designed to combat its spread online. As such, this does not mean that there aren’t any elements of the plan that countries around the world can learn from. The underlying principle of oversight should be something countries weigh more heavily as misinformation multiplies rapidly on popular social network platforms. As much as the right to speech should be protected, so should truth in political settings.

Featured Image Source: Reuters

Comments are closed.