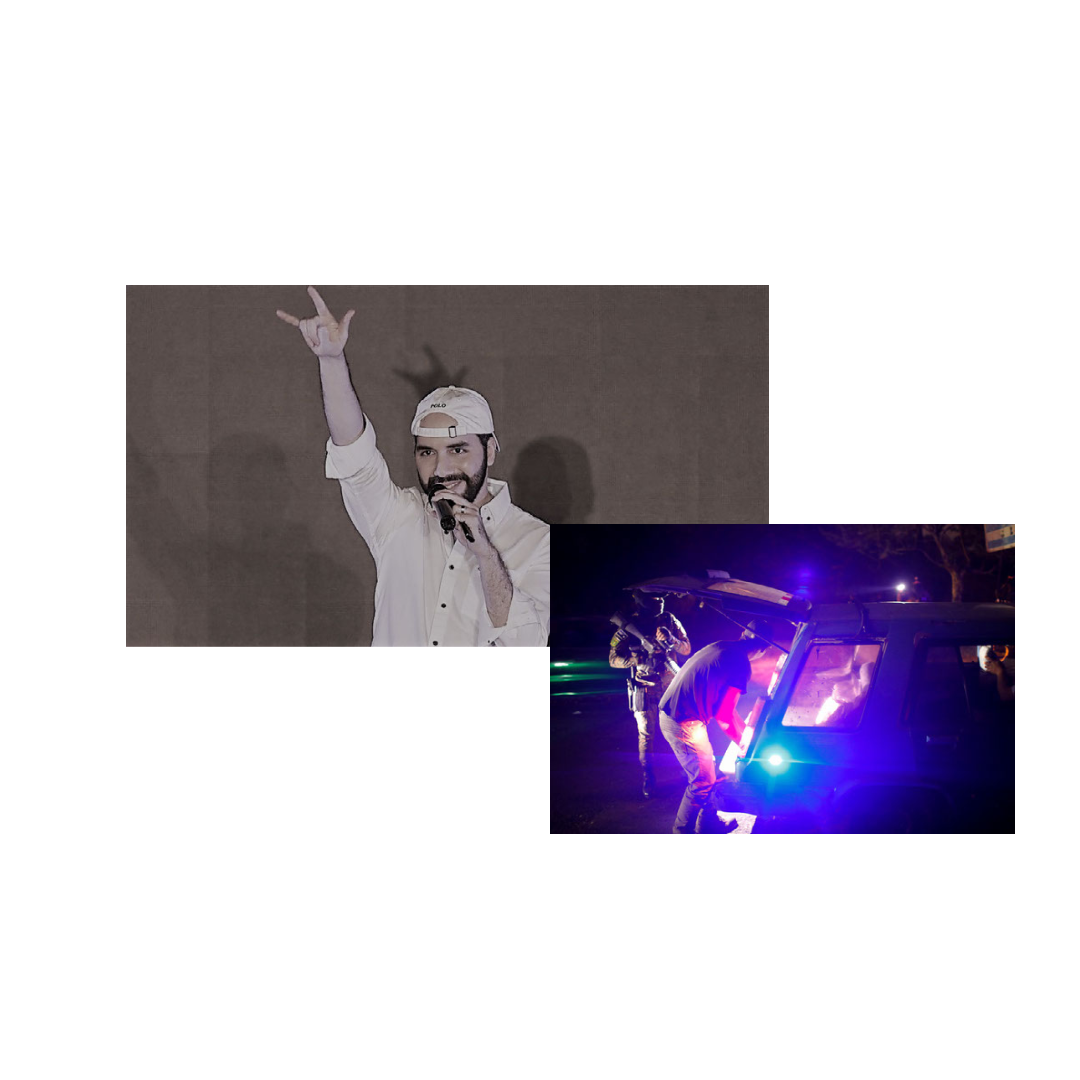

In 2021, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele described himself as “the coolest dictator in the world” on Twitter. If Bukele limited his eccentricity to Twitter, such a declaration would cause about as much harm as Elon Musk’s memes. However, between planning to promote Bitcoin in Miami while chaos consumes his country at home and exploiting his populism to destroy El Salvador’s institutions, Nayib Bukele is anything but a harmless politician.

Adorned with a backwards-facing baseball cap at all times, Nayib Bukele capitalized on his youth to promote himself as a clean break from the corruption and failures of successive administrations that governed El Salvador since the end of the 1992 civil war. Although a character as unorthodox as Bukele would seem like a weird fit at best for a role as important as the presidency, El Salvadoreans had much reason to try something new and daring. The old guard of politicians systematically redirected millions of public funds into their own coffers and offered indistinguishable policies, while their country suffered from some of the highest violence rates in the region, remaining mired in poverty and a brain drain crisis. Despite its perennial struggles, El Salvador receives little in the way of external help. As the U.S. deportation of thousands of El Salvadoreans show, power brokers within the Americas have little regard for the country’s welfare.

For all of his quirks, Bukele seemed to offer the best chance at a new start. As mayor of San Salvador, El Salvador’s capital city, Bukele presided over extensive public works projects and exploited the power of social media to expand his popularity. While an unabashed populist, he ran on an anti-corruption platform, promising to establish institutions that would clean up graft. For those fed up with the complacency and failures of the old order, Bukele offered the credentials of a leader suitable for the 21st century.

At first glance, Bukele’s administration seems to impress. Visible infrastructure improvements, better welfare services, and sustaining a decrease in crime rates that began before Bukele took power are all reasons cited by El Salvadoreans that contribute to Bukele’s sky-high approval rates: ~90%, almost unheard of even in flawed democracies. Behind the veneer of policy success, however, lies political machinations that range from erratic to downright dangerous for El Salvador’s civil institutions. Enshrining Bitcoin as a legal monetary tender in El Salvador may have gained him much favor among crypto fanatics in Silicon Valley, but does not help to stabilize an economy and populace that mostly lives paycheck-to-paycheck.

Other moves by Bukele are less tinged with meme-like qualities and reek more of insidious power-grabs. He used the army to intimidate opposition politicians into voting for policies favorable towards his administration. Although, after a parliamentary election in 2021 which saw his New Ideas party win a landslide majority, such moves became unnecessary. Having already removed numerous judges and judiciary officials who produced unfavorable rulings in early 2021, Bukele and his supporters moved to impose arbitrary term limits that would force almost a third of all judges into retirement. This would allow Bukele to pack the judiciary with favorable candidates and erode judicial independence. As a leader who likes to portray himself as the quintessential modern politician, his autocratic tendencies bear a striking resemblance to numerous dictators of the old. Less Emmanuel Macron and more Hugo Chavez, President Bukele seems inclined to use his youth as a weapon to gobble up positions of power instead of a tool to push through difficult reforms.

Even his achievements, mainly those involving crime and safety, have come under increased scrutiny over their means. An El Salvadoran newspaper exposed Bukele’s government for collaborating with the gangs that proliferate in El Salvador’s civil society in hopes of reducing crime. Such practices are not new; previous administrations also worked with imprisoned gang leaders during politically sensitive times to create favorable conditions for reelection. While Bukele denies any cooperation with criminal gangs, foreign observers suggest otherwise. For a president who seeks to differentiate himself from the past policies and failings of El Salvador’s political establishment, such a policy undermines his integrity and credibility.

Worse still, the illusion of security that Bukele created faces imminent collapse. On March 27, El Salvadoran police recorded the highest number of murders in a day since the end of the nation’s bloody civil war in 1922, as dormant gang conflicts began to rekindle once again. Bukele’s government declared a state of emergency in response to the surge in murders, unleashing a new set of draconian prison laws in an attempt to deter further violence, ranging from doubling prison sentence lengths to suspending civil liberties such as the right to legal counsel. Such measures may only serve to perpetuate the cycle of destruction consuming El Salvador ever since the 1990s, as gangs and the government respond to each other’s escalations with tit-for-tat violence.

Between the erosion of already-weak civil institutions by Bukele’s administration and the ever-persistent power of El Salvadoran gangs, the El Salvadoran people continue to bear the brunt of the devastation left in their wake. The tug-of-war between El Salvador’s underworld and the government to assert control over security continues without end, evidenced by the ongoing state of emergency. While Bukele continues to publish Twitter posts highlighting his tough-on-crime persona and policy set, the fact remains that thousands die each year from homicides in his country of 6.5 million, exposing government-brokered gang truces as a mere folly. Even Bukele’s much-cherished Bitcoin pet project fails to accomplish anything the president promised. Nine in ten El Salvadorans do not even understand how Bitcoin works. The only achievement made by introducing Bitcoin as legal tender in El Salvador was to destabilize the country’s already-precarious debt situation further, worsening an already moribund economy. Far from a new start for El Salvador, Bukele’s flurry of novel policies have done worse than to underdeliver, weakening El Salvador’s fragile civil institutions.

Unfortunately, Bukele’s eccentricity and thirst for authoritarian power marks the norm, not the exception, in Latin America. Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador splurges on grandiose populist projects and antiquated industries with little oversight at the expense of the wider Mexican economy’s health. Brazil’s institutions, weakened by the fallout from Lava Jato, continue to crack under Jair Bolsonaro’s irresponsible and conspiracy-loving rule. Daniel Ortega, longtime Sandinista President of neighboring Nicaragua, has all but eviscerated his country’s political opposition. Venezuela continues to languish under the kleptocracy of Nicolas Maduro and his cronies even after almost a decade of protests. Democracy continues to approach the point of terminal decline in a region left behind by globalization and the world’s great powers. The region’s autocrats have diverse origins: some ram through unfeasible socialist policies; some plunder their own country’s resources; some promote conspiracy theories at a rate that puts Donald Trump to shame; some fall from former revolutionary to dictator; some court the adulation of crypto-loving tech bros. But all of them share the lust for power and rampant disregard for democratic institutions. Their corruption of Latin American politics, buoyed by widespread disillusionment with the establishment, mean that Latin America and its people seem nowhere close to escaping the malaise they have to endure on a daily basis.

Featured Image Source: Reuters

Comments are closed.