Over the past few months, many organisations in Russia have been faced with new pressures from the government which severely limit their ability to function. This came at a time when United Russia — the political party most loyal to Putin — sought to secure a majority in the Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament.

Dozhd (TV Rain) is a channel that advocates free speech and is in prominent opposition to the government. With the motto of “talk about important things with those who are important to us,” they are frequently critical of Putin and are — from a Western standpoint — arguably much more truthful in their coverage.

They were disconnected by Russian TV network providers in 2014 over a controversy relating to a poll comparing the Siege of Leningrad to the 1812 capture of Moscow. However, the owner of the channel Natalia Sindeeva suggested that this was due to the broadcast of Navalny’s investigation of corruption of Russian officials.

In August of 2021, the outlet was declared a ‘foreign agent’, joining the ranks of many others, including online newspaper Meduza that now operates out of Latvia.

The term refers to foreign-funded organizations that the government claims are engaged in political activity. This was part of a bill as part of wider amendments to the criminal code aimed at tightening Putin’s grip on the media, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and public associations. It came at a time when government rhetoric was increasingly focused on Russian sovereignty.

All organizations with such a label are required to include a disclaimer in all published content, including everything published prior to the ruling. The term translated into Russian — “ Иностранный Агент” — also has strong links to Soviet espionage, and is overall undesirable for a media organization. It evokes a strong imagery of ‘the other’ used in political discourse and popular culture throughout the Cold War.

Forgetting to add the disclaimer can mean hefty fines or even imprisonment.Nevertheless, journalists are finding ways to incorporate this into their coverage. For example, Meduza seems to have taken the label in stride: “Hi, everyone! We’re Russia’s latest “foreign agent”!” writes the newspaper following the ruling in April.

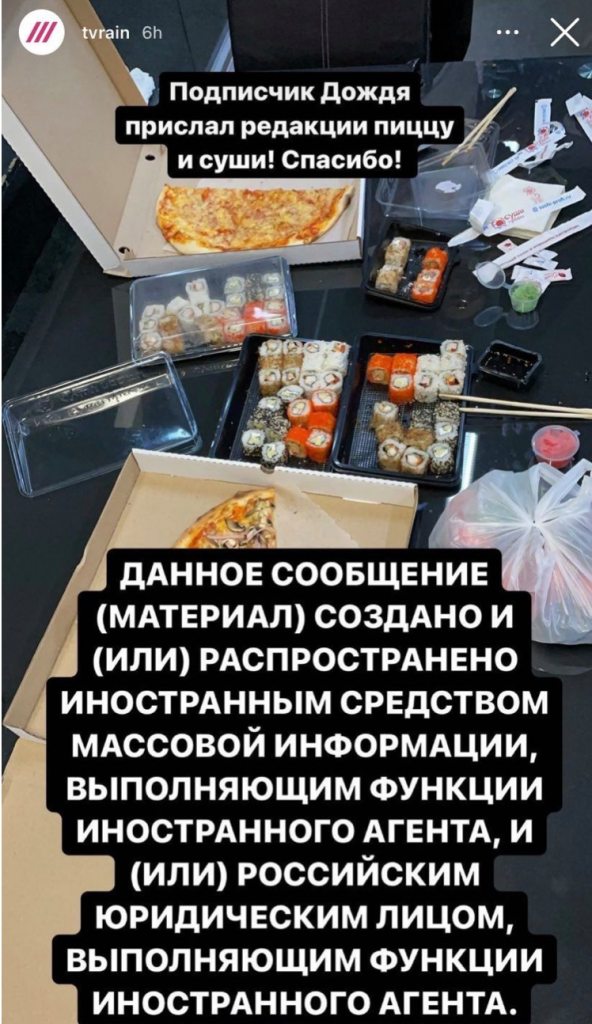

On the day Dozhd made the foreign agent list in August, they posted an Instagram story of pizza and sushi sent into their studio by viewers.

The bottom half of the picture was taken up by the disclaimer: “THIS NEWS MEDIA/MATERIAL WAS CREATED AND/OR DISSEMINATED BY A FOREIGN MASS MEDIA PERFORMING THE FUNCTIONS OF A FOREIGN AGENT AND/OR A RUSSIAN LEGAL ENTITY PERFORMING THE FUNCTIONS OF A FOREIGN AGENT.”

Sonya Groysman and her colleague Olga Churakova, from the independent news site Proekt, were labelled ‘foreign agents’ in July. To deal with this, they made a podcast about it.

“Hi, You’re a Foreign Agent” (“Привет, ты иноагент”) is a podcast hosted by 27-year old Groysman with Churakova, documenting the experiences of being foreign agents and how to move forward.

The first episode lasts only a minute and 44 seconds, as Ms. Groysman herself attempted to read the disclaimer she described as “degrading” in an opinion piece written for the Moscow Times. She laughed as she read the disclaimer, which is the attitude many journalists have begun to adopt.

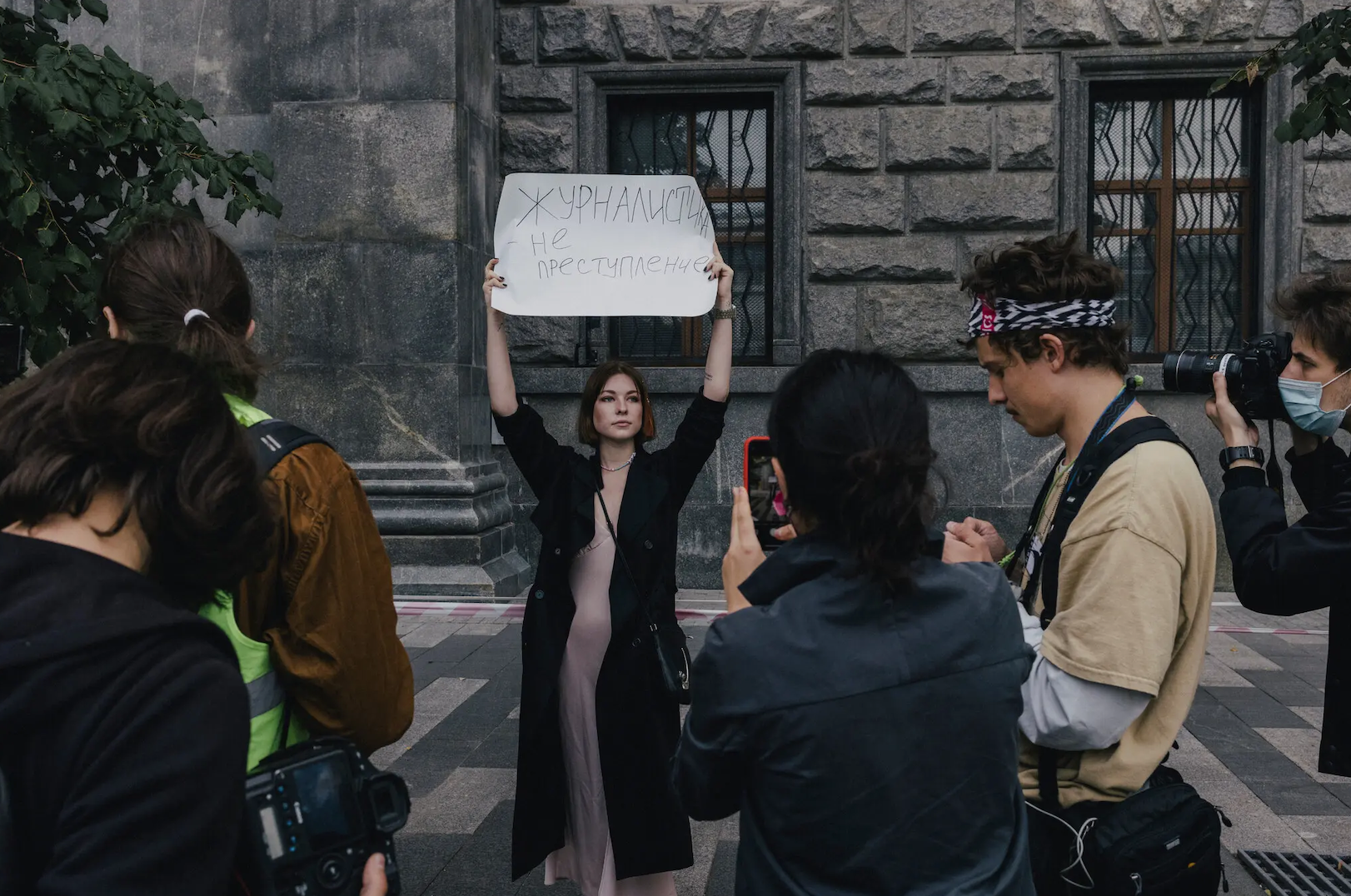

Despite a ramped-up crackdown on the media, journalists and prominent opposition figures continue to spread awareness of the increased restrictions on free press.

As well as being foreign agents, Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) have been given a new designation — as of early July they are officially an ‘extremist organisation’. As per a new law signed by the President just one month earlier, those designated as ‘extremists’ are banned from running for public offices and face threats including fines and imprisonment. According to the Commonwealth of Independent States Anti-Terrorism Center, Mr. Navalny’s FBK finds itself among groups such as Al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

The timing of the new law or the ruling following it is not lost on anyone.

The crackdown comes at a crucial time for Putin. The Duma elections (Russian’s lower legislative house) happened from the 17th-19th of September, and it was important for Putin to secure a win and appear strong in front of the country.

One of the reasons Putin needed to crack down on the media is because there have been many documented instances of election fraud. In order to engage in the large-scale fraud reported by many outlets, it is better to not be scrutinized by unfriendly media. Hence, it would be in Mr. Putin’s interests to limit electoral coverage to only those outlets he controls.

Second, the Russian government undertook a rather unprecedented attack on foreign outlets throughout the election process. This involved Navalny’s so-called “Smart Voting.”

Though no significant opposition candidates were able to run for election (many candidates were banned from running due to allegations of owning foreign assets or receiving foreign funding), some with a more oppositional stance did find themselves standing for election.

In order to ramp up the pressure on United Russia, Navalny and his team focused efforts on their tactical voting strategy developed in 2018. Every district was assigned one candidate most likely to beat their United Russia opponent if voters combined their efforts. This “Smart Voting” campaign has been ruled illegal by Russian courts.

Moreover, in the run-up to the election, the website containing information about opposition candidates was banned in Russia. Google and Apple also received threats from the Russian government to remove this information from their platforms.

In a surprising turn of events, the companies complied. The Smart Voting app was removed from the Apple and Google stores in Russia. Google Docs with candidate information were blocked, as were YouTube videos. Popular messaging app Telegram also blocked the Smart Voting information channel.

“This content is not available on this country domain due to a legal complaint from the government,” read the YouTube text.

Lack of real opposition or coherent media coverage allowed United Russia to “win” almost 50% of the vote nationally. It has also set a frightening precedent for both domestic and international news and media organizations.

Aside from involving international organizations and corporations, the government has also started to turn on foreign journalists. In August, BBC Moscow correspondent Sarah Rainsford faced de facto expulsion from Russia. According to Reuters, she was denied an extension of her visa.

This is the first case of its kind in two years. Russian authorities stated that this was in retaliation for the poor treatment of Russian journalists on by United Kingdom, including failure to provide them with visas.

In her commentary in New Statesman, Ms. Rainsford says she’s been labelled as a ‘security threat’ by the FSB — Russia’s principal security agency.

Aside from showing deterioration of relations between Russia and the UK, this is a clear sign of authoritarian crackdown. However, it is hard to know the extent of what the restrictions mean at this moment in time and precisely what sparked them.

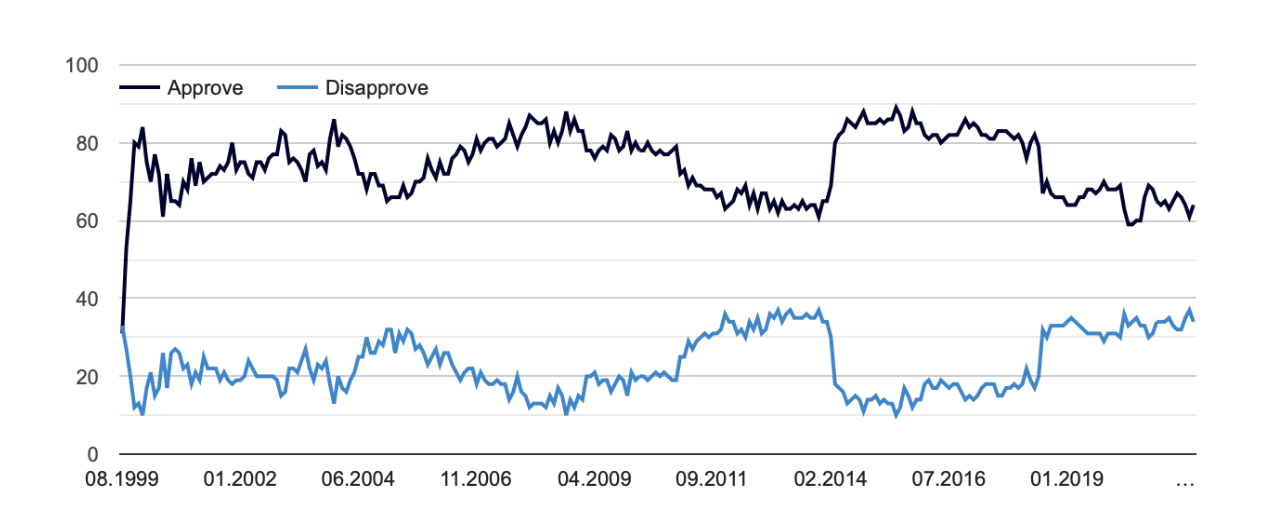

One possibility is that increased resistance has scared the government, especially considering the comparatively low popularity of Putin with his earlier terms. According to the Levada Center’s polling data, his approval ratings have been more or less steadily decreasing since around 2016.

Perhaps these restrictions were one-offs, just to secure the electoral win and maximize control over the media to ensure no dissenting opinion.

However, it seems much more likely that this is the beginning of an extensive policy of repression of online media that has remained mostly free throughout previous presidencies.

The internet was once a safe haven for those dissatisfied with the Russian regime to voice their opposition. Now, almost no one is safe. It will be imperative, both for the safety of Russian journalists and citizens as a whole, for the global world to follow what comes next for the Russian press.

Otherwise, it may be too late.

Featured Image Source: New York Times

Comments are closed.