Jonah Hill and Miles Teller, according to friends I’ve spoken with, successfully romanticized the arms contracting business in the 2016 movie War Dogs. Guns, girls, excitement and fear all play into the fetishes in a boy’s mind should he be raised amidst American capitalism and the international military industrial complex. The film focuses on those who exploit the arms business, though there is much more to tell on the other side: on the power dynamics between countries created by missile capacity, which enables private contractors – what Hill and Teller brand as war dogs – to reap their profits and adventures.

Those power dynamics and the situations those dynamics manifest can be just as exhilarating as the subplots of the war dogs finding ways to trade in missiles and arms. The Cold War may have ended formally with the Soviet Union’s collapse, but a cold war with Iran leaves its mark in our politics everyday. Out of fear for Iran, or other threats to international stability, administrations like the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Israel, India, Pakistan, still compete to stockpile and develop more missile defense than their rivals, and partner with allies to spend massive amounts of money on arms deals. In the first three months of 2021, the US spent approximately $7.5 billion on missile defense-related contracts. The Department of Defense’s 2021 budget proposes approximately $20 billion in missile defense spending, and $30 million on nuclear modernization; this contributes to keep US military spending above the next 10 countries with highest military spending, combined.

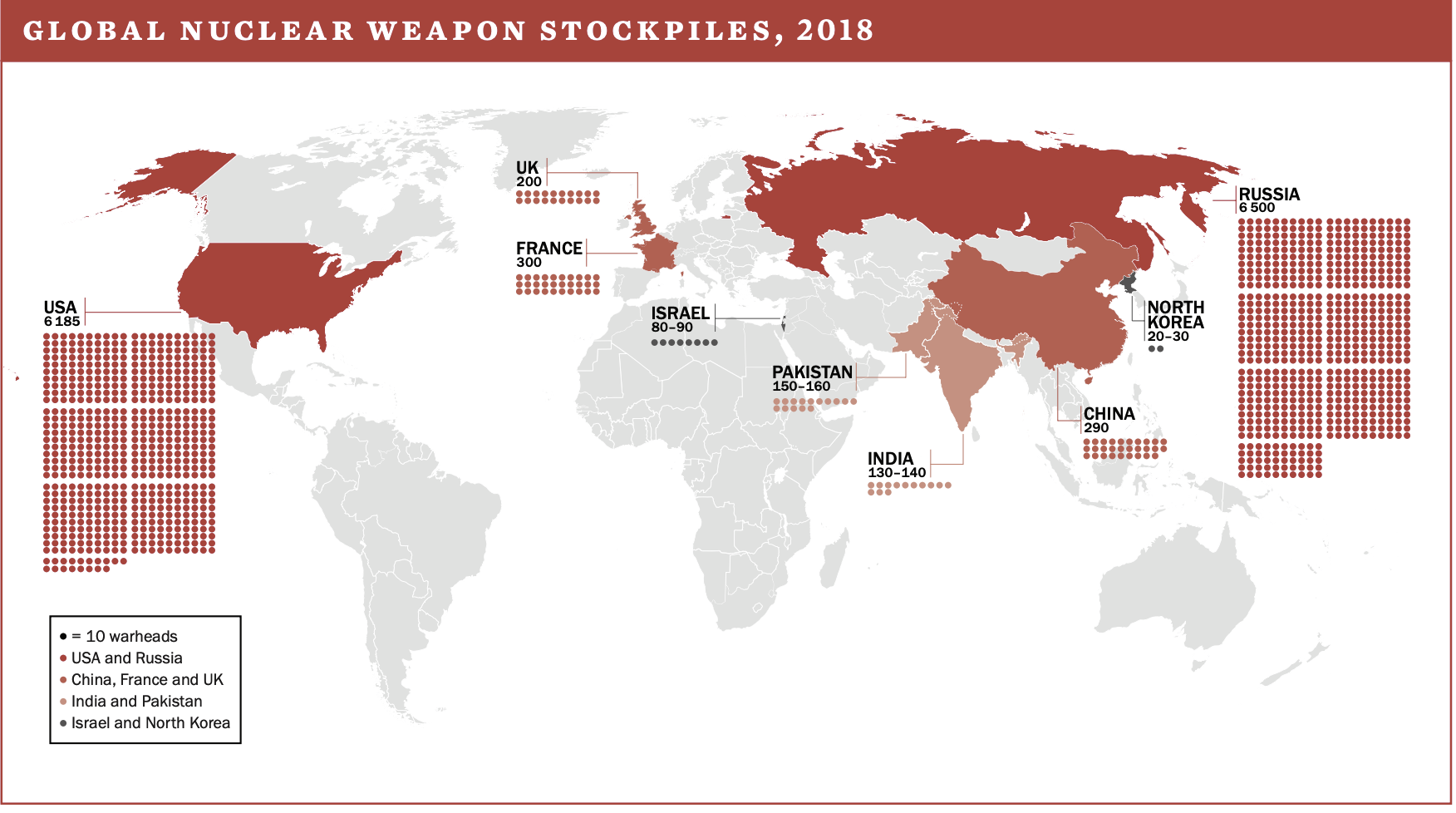

Regarding nuclear defense, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons allowed only the five permanent members of the UN Security Council to stockpile nukes. Yet nine nations are known to possess a cumulative 13,400 nuclear weapons, of which approximately 1,800 are kept in a state of “high operational alert” according to the SIPRI 2020 Yearbook. India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea are all believed to possess between 30 and 160 nuclear weapons.

One can go to great lengths speculating why nearly 2,000 nuclear weapons are ready to launch. The absurdity of such a form of diplomacy confronts us in the 1964 war-comedy, political commentary Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The focus is less so on who supplies missiles and arms, as in War Dogs, but on those who can use and launch them. We are at the vulnerable whim of a few actors, government and military officials – who are evidently not always so stable – keeping our world from nuclear winter. The way those leaders communicate on the world stage today casts doubt on whether the last resort will be left for last – that is, whether heightened tensions and abrasive discourse will not lead to war. That fear is evidently felt worldwide, as countries negotiate and stockpile ever more arms. While the amount of nuclear warheads decreases little by little each year, the technology and mass of missiles increases without sufficient public reflection, passed off as defense programs. What we have to defend is unclear, be it democracy or imperial interests.

Threats and provocations reported in the media, luckily, do not lead to action as often as they are made. To be sure, the SIPRI Yearbooks report more armed conflicts last year than in 2019, which reported more than 2018, expressing a rise in armed conflict overall. However, the 2020 report did state the decrease of armed violence in particular states, correlated with international negotiations supporting peace with those states. Arms deals made by the war dogs in 2016 did not lead to a world war on screen. This situation reflects the real-world arms development and trade, which sustains a status quo of military spending and stockpiling regardless of the need for such weapons.

Missile development and stockpiling is not just a preparation for chaos, but can be seen as a form of political maneuvering, an expression of power and influence. An offhand example is North Korea’s most recent ballistic missile tests, just after President Biden’s visit to Japan and South Korea. Japan and South Korea confirmed that this past February, North Korea tested missiles for the first time since US President Joe Biden took office; ballistic missile tests followed just days later.

News reports point to Biden’s inauguration as a significant timestamp, as the US has been heavily involved in nonproliferation and demilitarization processes with North Korea and others for generations of presidents.

The last tests before these, of this nature, came amidst a stall in US-North Korean negotiations in 2020. The BBC’s reporting of the recent tests portrays these as an attention-grabbing ploy; they also affirm North Korea’s capacity for engaging in war, which in today’s political landscape grants a state a seat at the table of international diplomacy. The US and its allies engage with North Korea, and more broadly, with any group which threatens militarization to prevent tests from leading to more.

One might wonder whether the US has authority to moderate conversations regarding warhead capacity. As the only country to have used a nuclear weapon in war, the US could not say it has been the most responsible with missile operations. US use of missiles continues to breach peacetime laws, deploying missile strikes abroad even after Biden’s inauguration.

This is not to say North Korea ought to feel authorized in its warhead development. The abuse of its citizens rightfully causes US president after president to call for scrutiny on the DPRK missile program, for fear of what the country would do with any leverage in international influence, or who they might supply missiles to, with what intentions.

This is not to say North Korea does not already have international influence – the threat of missile development is enough to influence the actions of states the world over. Like Iran, North Korea makes headlines and finds its way into frequent defense conversations. Contracts and military cooperation is increasingly built on shared concern for the motives and movements of North Korea and Iran.

In the case of Iran, shared concern has driven multiple Arab countries to recently normalize their relations with Israel, forgoing regional conflict to begin cooperating in the name of defense against Iran and its proxies. Like North Korea, Iran fails to uphold UN treaties and resolutions related to missile development and human rights, has failed to uphold its side of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – and continues to make efforts towards enriching uranium to nuclear warhead-capacity. Its role in the world’s worst humanitarian crises supports the priority goal by the UN Security Council permanent members, of preventing Iranian nuclear and further missile capability.

The US and its allies have long fought the extremist groups across the region under the title of various wars, all under the broader War on Terror. Iran supplies a number of these militias in the Arab world with arms and training. As previously written on terrorism, there is a question of what justifies attacks in civilian communities, or rather who is allowed to justify their attack to the international community; Iran’s proxy wars fit the category of unjustified violence. Historically supplying missiles to groups radically oppressing human rights is enough to give concern for what Iran’s proxies’ success with more and better missiles could mean.

So, perhaps it is justified to mediate Iranian and North Korean missile development and stockpiling, or others who support threat to global values. Yet, the US is not innocent in regards to its use of missiles and arms, nor its role as an arms exporter. The US has supplied weapons to various administrations which have inevitably resorted to unjustified violence.

Uganda is not among the largest receivers of US missile defense, but does receive significant support in the form of arms and training. Some may be more easily justified, such as the US using Ugandan relations previously to pursue warlord Joseph Kony, and radical insurgents in Somalia. Yet, domestic human rights abuses domestically call into question the motives of the Ugandan government should those with access to the missiles grow tired of US hands in their country; a past example of support gone awry is that for the Taliban during and partly after Soviet invasion in Afghanistan in the 1990s.

A Ugandan opposition lawmaker called for an end to US military support in 2018, while violence against citizens continued to rise (even to this day). Granted, US methods used of silencing dissent mentioned by Uganda leaders were only inherited from the past US president, leaving Biden to rectify a global image. Yet military aid to Uganda has yet to be reviewed by the new administration and continued support has not yet been conditioned on improving human rights.

The example the US sets plays into the hands of this and other autocratic regimes As the New York Times reported, a Ugandan military official justified his own country’s use of unmarked vehicles by pointing out that the US and Britain also adopted the same tactics for US’s use of unmarked cars to abduct dissenters, or whom he called “hard-core criminals,” to validate their own use. Amidst contest of the most recent election, the reelected President branded some of these protestors “terrorists.”

Equally concerning for military support to Uganda are Ugandan relations with China and North Korea. That Uganda can receive military and missile support from two sides of a global defense conflict highlights the counterintuitive nuance to military aid, and the way a state can maneuver international conflicts to develop its own military and political agenda. This idea is reinforced by US’s support of both sides in Mexico’s drug war. The picture painted is that international regulation of missile development and stockpiling at times overpowers consideration of states’ track records on human rights and diplomacy.

Bilateral arms relations follow personal motives as well. The US puts aside concern for Uganda’s domestic issues to garner influence and authority within the state, and China and North Korea believe themselves capable of the same or of further influence through their military support in the country. Imperialism rears its head through international military power taking precedence over human rights concerns.

The US is not the only state to put imperial interest above foreign conflict. A recent report commissioned by Rwanda determined France was significantly responsible for the Rwandan Genocide, supplying military support to the government throughout the massacres and human rights abuses of the 1990s. France’s geopolitical interests in Africa caused them to ignore the abuses made by the administration they funded. For Russia as well, military engagement and support with Serbia has prevented sufficient justice for the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, which claimed about 8,000 lives. More powerful states seem to use missile supply and relations to further their imperial interests, and disregard the consequences of militarizing unstable or dangerous regimes. When the elephants fight, it’s the grass that suffers.

The US-Israel relationship, though not entirely based in military cooperation, is certainly sustained in part by defense programs. Shared concern of the threats of radical extremism, partly related to Iran’s influence, and their proxies’ threat to Israel’s existence by consistent missile launches into Israeli villages, lead to the collaborative development of the missile defense systems Iron Dome and David’s Sling, which intercept short and medium-to-long range rockets, respectively, and other airborne threats. This defense system patently protects the lives of millions. Less clear is the benefit to the US of bringing these systems stateside, as announced by Raytheon Technologies and Rafael Advanced Defense Systems last August.

Without a current airborne threat to the US, the plan is possibly unwarranted, or somewhat overly preventative. Having the system and not needing it is better than the alternative. Yet, having it at all goes on to stimulate other states’ perceptions of missile development, likely leading to more missile development and stockpiling by them, then reciprocated in response by the US, and so on goes the cycle. This does not seem a direct strategy for peace building. We could not expect any one country to be the first to give up their arms. Does this leave us in a state of chicken, each country moving its missile program forward until one gives in or they all reach an explosive head-to-head? It certainly keeps the war dogs employed – Raytheon Technologies an American multinational aerospace and defense manufacturer, anticipates $63- to $65 billion in profits this year. It leaves the rest of us only able to find comfort if we are at the forefront of missile capability.

Featured Image Source: U.S. National Archives

Comments are closed.