A Hong Kong resident died on February 5 after contracting the coronavirus, making him the second victim to succumb to the epidemic outside of mainland China. Though Hong Kong has remained relatively unimpacted by the outbreak, coronavirus’s effects have far-reaching implications for politics in the territory.

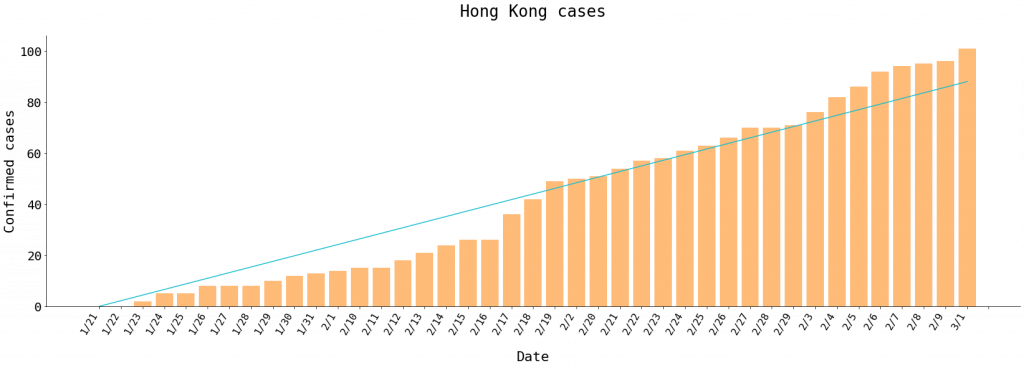

In the past month, the coronavirus from Wuhan (recently dubbed COVID-19 by the WHO) has infected tens of thousands and killed hundreds, mainly affecting patients in mainland China. In Hong Kong, the epidemic has been limited: as of March 1, around 100 residents have contracted the virus and one died while traveling in China. The outbreak comes at a tumultuous political moment for Hong Kong, which has been roiled by massive protests challenging the Chinese Communist Party’s role in governing Hong Kong and the status of democracy in the city. As a movement intended to disrupt public life and draw jam-packed crowds, the protests face a deadly enemy in the virus and the concomitant standstill in public society.

Protesters facing disease

The COVID-19 outbreak arrives at a time of deep suspicion among Hong Kong natives toward the Lam administration, with citizens doubtful of Hong Kong’s autonomy from the mainland Communist government. As Jen Kirby writes for Vox, the recent protests “intensified distrust of Lam’s government … Her government’s crackdown on the demonstrators convinced protesters that China, not Lam, was making the decisions.” In this political environment, the CCP’s reactions to the epidemic are under additional scrutiny. The Lam administration’s recent controversy weakened Hong Kong citizens’ conviction that their government is working to safeguard the interests of the people. The loss in faith comes as a headache when swift, sweeping policies are needed to mobilize collective action against the spread of the virus.

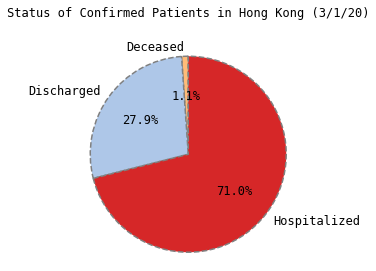

As seen above, the spread of the coronavirus remains linear rather than exponential. 28 percent of patients have been discharged, a testament to Hong Kong’s medical care. Nevertheless, Chief Executive Carrie Lam came under fire for waffling on official guidelines concerning face masks, which served as a symbol for the protests in Hong Kong. She issued contradictory statements on the face masks, intended to shield wearers from infection, first arguing that face masks should be reserved for medical workers, then reversing her position and apologizing. On February 8, Hong Kong imposed quarantine rules on mainland Chinese travelers to prevent the virus from spreading further — visitors from China were required to stay isolated in hotel rooms or government-run quarantines. Although the policy had effectively limited the influx of visitors, many residents thought it came far too late into the crisis.

Though the past few weeks of unrest paints a grim picture of Lam’s government as ineffective and unreliable in the eyes of the public, it is still unclear what effect the coronavirus will have on the government’s long-term legitimacy. To help forecast the effects of disease crises on authority, we can turn to theories of crisis management and examine the sources of political legitimacy in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong and the right to govern

Explanations for why a citizenry might choose to accept a regime’s right to govern can be classified as procedural or outcome-based. Citizens who care about procedural legitimacy might ask: do people have input on the government’s decisions, through fair elections, trials or accountability from leaders? Outcome-based legitimacy focuses on the results of policies, as perceived by the people: How did the state’s decisions influence outcomes in public health, economic growth or collective security? The basis of the Hong Kong state’s legitimacy matters when discussing its approval among a suspicious and unruly public.

In one view, crises such as epidemics sap political capital and foster distrust by obscuring how elites craft policy, regardless of the outcome of their decision; in other words, crises damage the procedural legitimacy of the state. Since decisions during crises are made in tense, hurried situations, the policy-making process tends to be more opaque and admit less input from citizens. Institutions, in long-lasting crises, inevitably falter and reveal internal fractures. When faith in government is already low, failures confirm for citizens that their suspicions were right: the state cannot, or will not, protect them.

In another view, a disease outbreak may eventually strengthen state legitimacy if the country emerges successfully from the crisis and returns to normalcy. The policies of disease control — quarantines, rationing, and travel bans — are seen as effective interventions in the crisis by a competent and strong state. Citizens may forgive the state for authoritarian tendencies in exchange for improvements in welfare. For instance, the Ugandan government emerged from the HIV/AIDS crisis with higher levels of approval and political capital; the public applauded what was seen as an effective and powerful strategy to combat HIV/AIDS.

Hong Kong’s government is unique due to its recent colonial past and the relatively high degree of civil liberties compared to mainland China. Drawing on surveys of public opinion in the post-handover era, Sing (2001) argues that the Hong Kong state relies on the outcomes of sustained economic prosperity and civil liberty for its legitimacy. When either falters, approval of the administration drops. Residents emphasized outcome-driven reasons to support the government, such as quality of life, rather than a procedural focus on democratization. Against this backdrop, the current protests can be seen as a consequence of public dissatisfaction with declining economic growth and civil rights.

The future of protests

To project the movement’s long-run outlook, we need to examine its underlying political and economic causes.

Looking from the perspective that the protests are a consequence of low political legitimacy, the Hong Kong movement, though ostensibly about politics, is at its core driven partially by economic anxieties. Just like in 2014, youth cite growing inequality, poverty and unemployment as some motivators for joining protests. In 2019, Hong Kong ranked among the most unequal cities in the world by its Gini coefficient, a number encapsulating housing, education, income and quality of life measures.

In 2014, Hong Kong was also rocked by massive political demonstrations in response to new legislation that allowed China’s government to pre-screen candidates for Hong Kong’s executive election. Dubbed the “Umbrella Movement,” the demonstrations swarmed city centers in Mong Kok and Hong Kong island with yellow umbrellas and blocked arterial roads. After three months of sustained protests, “exhaustion and internal fractures” caught up to the demonstrators and the protests petered out in December of 2014.

Observers of Hong Kong politics have noted a few key differences between the current protests and the Umbrella Movement. First, the government in 2014 did not grant any concessions to protesters, despite enormous social and economic pressures. Protesters in 2019 achieved a victory when the Lam administration reversed its decision on the extradition treaty with China that would have allowed Chinese criminals residing in Hong Kong to be tried in the mainland justice system. Second, participants in the current protests greatly outnumber those from the previous ones. At its peak, the Umbrella Movement had between 100,000 to 500,000 protesters. Today’s protests top one million. Lastly, many of today’s demonstrators were also participants in the Umbrella Movement and have applied lessons from the past to today’s protests. Decentralized structure and extensive use of social media have bolstered the protesters’ reach away from the watchful eye of law enforcement.

Source: Stratfor Worldview

The coronavirus outbreak has resulted in a standstill in public life across China and similarly resulted in a decrease in protests in Hong Kong. Guidelines from public health organizations advise people to stay indoors and avoid large public gatherings. Though many protesters state that the coronavirus has deepened the movement’s unity against overreach by the Communist Party, most Hong Kongers need little urging to stay home: the specter of the disease has resulted in most citizens prioritizing their own health and well-being over the movement.

Whether the movement endures beyond the resolution of COVID-19 depends on public dissatisfaction with quality of life in Hong Kong. At the present, coverage of the governmental response to the coronavirus is still in flux, and judgement of its efficacy will need to be reserved for after the containment of the virus. Though public opinion currently disapproves of Lam’s policies, the tide will turn if treatments and containment strategies turn out to be effective.

As Hong Kong enters another quarter of stagnating growth, the one-two punch of political uncertainty over protests and the peril of coronavirus will pressure Hong Kong’s already beleaguered shopkeepers, financial workers, and households. If Hong Kong’s GDP does not bounce back rapidly from COVID-19, public perception of the protests may switch from noble rebels to bringers of economic misfortune.

Regardless of the longevity of the protests, Hong Kong’s residents on any side hope for a swift end to the crisis that has hurt so many.

Featured image source: Jerusalem Post

Comments are closed.