The GM strike, beginning in September of 2019, is set to be the largest strike of the past 18 years. In fact, 2018 as a whole saw the largest number of strikes in decades and support for labor unions has polled at a 20 year high with candidates like Bernie Sanders highlighting their importance in his economic and political strategies. Many left-leaning individuals often express admiration for the union golden era of the 1940s and 50s, when there were sometimes as many as 400 strikes of over 1000 people per year and union membership was at a historic high. With all the positive rhetoric surrounding unions, it may be difficult for someone to understand why anyone, aside from cartoonish caricatures of capitalist pig-men in coat and tails, would ever dislike unions. However, the unintended consequences of the GM strike highlight the ways in which the main tool of unions, the strike, is deeply flawed from a political economy perspective. With a decline in union membership and manufacturing in the US and the interconnectivity of global supply chains, the benefits of a strike fall to fewer and fewer hands while the direct consequences of the strike can still cause great harm to the local economy.

Many in America live paycheck-to-paycheck, and strikes can have a strong impact on the financial well-being of the strikers who have to tighten their belt or go into debt. In communities that rely on money from manufacturing workers to spend, this can cause an intense ripple effect that can be felt for miles. If Bob the tire quality control specialist doesn’t have any money, then he doesn’t buy coffee from his local diner, which in turn affects the income of the cooks in the diner who may then forgo purchases at other stores. This is essentially the so-called “virtuous cycle” of economic growth working in reverse, which can cause an intense contraction, which some fear could cause a recession locally as well as statewide. Thusly, even ordinary working people in an area attached to a factory town have a vested interest in ensuring union strikes are ended quickly and do not happen often. This generally results in anti-union legislation or in legislation to cement union desires into public policy without causing the type of damage typically associated with strikes.

Locals near an autoplant are not the only people that have direct financial stake in ensuring strikes don’t happen. Suppliers up and down the chain are also deeply affected and even more intimately attached to these strikes. Within GM itself, roughly 10,000 non-union workers have been placed on furlough as a result of the strike mentioned at the beginning of the piece. This is because without unionized labor in certain fields, the whole cycle of production shuts down, and everyone involved is unable to continue working. With chains of supply so directly interlinked, a stop at any point, union or non-union, could cause a work-stop for all other points in the chain. Workers in Canada and Mexico have also been placed on unpaid furlough, causing them to lose income without any possibility of gain and with no incentive on behalf of their American counterparts to represent their competing interests. Auto parts suppliers to GM, such as American Axle & Manufacturing Holdings, have already reported having to lay off workers due to projected losses from the strike. Car dealerships, which are up the supply chain from the plant, have reported hardships in servicing GM cars due to shortages of materials as well. This point brings me to the last victim of strikes: the wider public.

America is fundamentally a consumption heavy economy. Our strength relies on our ability to purchase and consume. Almost 70 percent of our GDP comes from consumption. Any reduction in consumption affects the economy as a whole in a big way, and strikes cause a reduction in production and consumption of the product in question and other products inadvertently. If prices or parts get too scarce, that causes prices to go up and consumers to be shut out of the market. Even worse than that, many states such as Tennessee rely almost exclusively on sales tax for government revenue (California still nets about 20 billion a year in sales taxes). A strike not only affects consumers but also affects the most vulnerable members of our society who rely on government sponsored welfare.

In conclusion, part of the reason for the decline in political support for unions is due to incredible destructive and disruptive power of strikes. While national labor standards laws can be achieved through the ballot box, the picket line drives a wedge between union interests and the rest of society. Unions should stick to grassroots and political organization because, while strikes can bring them short term gains, they hurts those around them and expose the single-minded interest that unions have for their membership and the ability to disregard and harm their community at large.

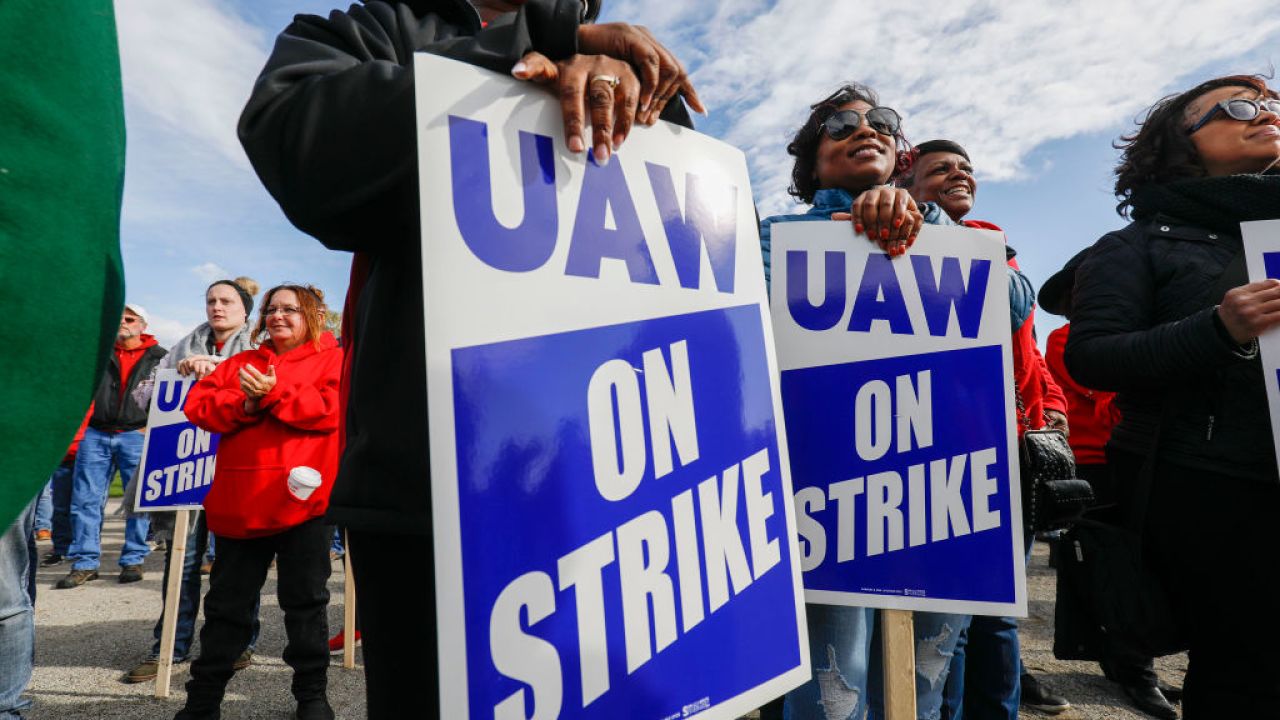

Featured Image Source: WXYZ Detroit

Be First to Comment