“This man may look intelligent but in fact is stupid.”

As evident from the quote above, Deng Xiaoping had a rather low opinion of Mikhail Gorbachev, the last President of the USSR.

Xiaoping did not believe in imitating the western model of success. While Gorbachev had tried to reform the USSR through westernized political reform such as the infamous Perestroika which led to his ouster and arguably the collapse of the Soviet Union, Xiaoping retained authoritarian rule even as he opened up the economy.

Emerging as the new de-facto leader of the People’s Republic of China following Chairman Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, Xiaoping led his country through far-reaching economic reforms that transformed the nation into the industrial powerhouse it is today. However, China’s new found strength also gave birth to new vulnerabilities for the country.

Fueling China’s exponential industrial expansion is its heavy reliance on energy, particularly oil. China became the world’s largest oil importer in 2017, surpassing the US. Approximately 70% of the country’s oil requirements were satisfied through imports in 2018 with the U.S. Department of Commerce expecting this to grow to about 80% by 2040. This dependence on foreign oil to run the country’s giant economic machine created what is known as “The Malacca Dilemma,” coined in 2003 by then-president Hu Jintao.

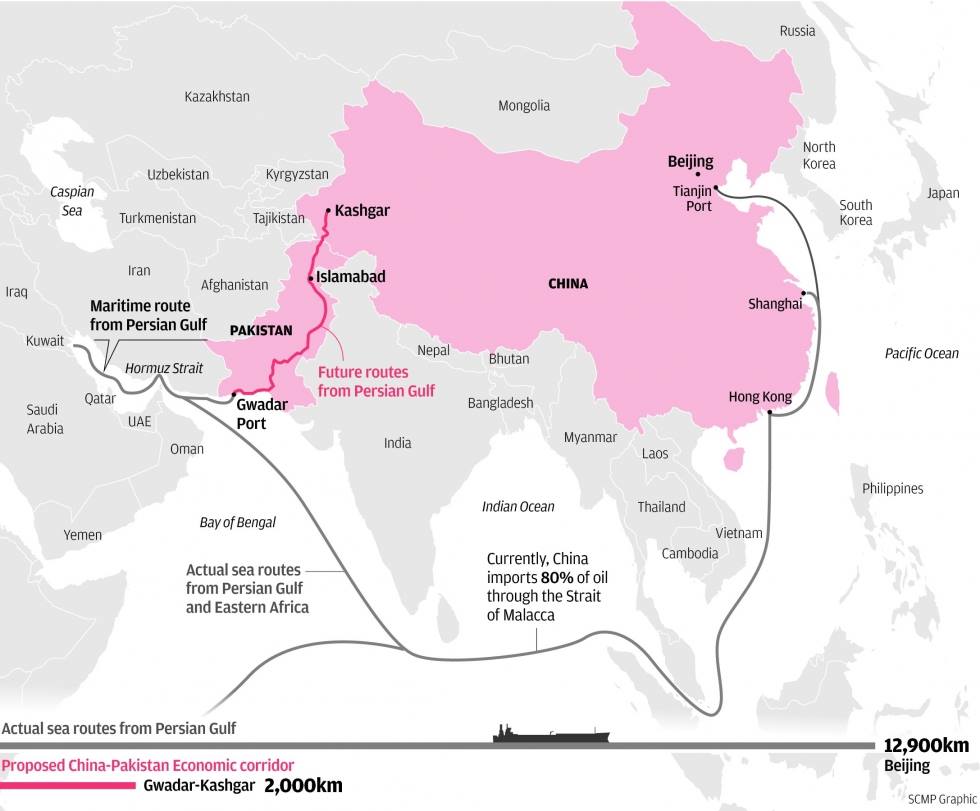

Most of China’s imports derive from the Middle East and Angola. Currently, eighty percent of China’s oil has to pass through the Strait of Malacca, a narrow stretch of water between the Indonesian island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. With Singapore, a major US ally that frequently participates in US naval drills, located at the mouth of the strait’s eastern opening, the Strait of Malacca becomes a natural strategic chokepoint. In the event of a conflict, the Malacca Strait could easily be blocked by a rival nation, cutting off China from crucial energy resources. The closest alternative is the Sunda Strait whose narrowness and shallowness make it unsuitable as a passageway for large, modern ships. Other alternatives such as the Lombok and Makassar Straits are much longer routes that would incur additional shipping costs estimated to be from around $84 to $220 billion per year, according to RSIS.

As such, the Chinese government has taken a number of steps to reduce the country’s over-reliance on the Strait of Malacca. These include the Kazakhstan-China Pipeline which connects the country to the oil-rich Caspian region and the Myanmar-Yunnan Pipelines which siphons oil and gas from the Bay of Bengal to the Kunming region of China, avoiding the Malacca Strait for Burmese oil imports.

The most effective way to avoid the Malacca Strait altogether would be to build a canal across the Kra isthmus of southern Thailand, providing an alternative shipping route. In an ideal scenario for China, Beijing would retain control over the area in return for building the canal, much like how the U.S. Panama Canal Zone operated before full control was handed over to Panama in 1999.

However, Thailand would be hard-pressed to accept such a deal. The country is not as weak economically or politically as Panama was during the 19th century and so would be much less willing to grant China the right to use and control strategically important territory .

Should China not be able to secure control over the area, the canal would be vulnerable to hostile entities and leave China stranded in essentially the situation it stands in today. Shipments would have to be unloaded and reloaded at both ends and the canal would itself become another strategic chokepoint. Also important is the estimated cost of the project, an estimated whopping $25 billion, and the logistical nightmare it entails.

In light of this fact, perhaps the most interesting and viable alternative is the Gwagdar-Xinjiang Pipeline. As part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Chinese government invested in a series of transportation and energy infrastructure development projects in Pakistan valued at $62 billion. The economic corridor would provide China access to Pakistan’s Gwadar port in the Arabian Sea. Nicknamed the “Crown Jewel” of China’s string of pearls, a network of Chinese naval facilities in the Indian Ocean, Gwadar is a deep-sea port in close proximity to both the Middle East and the Strait of Hormuz.

The most important advantage of the Gwadar-Xinjiang pipeline is that it enables China to bypass the Malacca Strait altogether. Middle Eastern shipping tankers could simply dock in Gwadar where the oil would be extracted and further transported to China through a series of pipelines. The Iran-Pakistan Pipeline could also be linked to Gwadar and potentially provide an additional avenue of energy imports to the Chinese industrial machine and increase the security of its energy supply. Although this option is comparatively more expensive than others, it notably maintains China’s connection to Middle Eastern oil supplies in an efficient and comparatively secure manner, should a crisis arise in the Strait of Malacca.

However, despite Beijing’s aggressive attempts at diversification, it will continue to remain dependent on the Malacca Strait in the short-term. The Kazakhstan-China and Myanmar-Yunnan provide only 400,000 and 420,000 barrels a day respectively, compared to the 6.5 million China-bound barrels that pass through the strait daily. As such, China is attempting to significantly expand its naval power projection capabilities to defend its access to energy.

One strategy is the development of the famous String of Pearls, a series of Chinese naval bases in the Indian Ocean. The string not only serves to protect China’s sea lines of communication that are crucial for seaborne trade but also provides an additional avenue of deployment points for the Chinese Navy. A modernized People’s Liberation Army Navy coupled with a ring of staging points across the Indian Ocean could provide China some semblance of security, but because of the US Navy’s heavy presence near Singapore, the Strait of Malacca would remain significantly vulnerable to a China-focused blockade.

As China’s shortfall in domestic production and energy consumption continues to grow, a viable new route will need to be established in the long-term. Deng’s reforms created lasting impact on the world’s most populous nation and propelled China to become a major player in the international stage. Yet they also created a supreme dependence on energy and the country lacks the natural resources to fulfill its needs domestically. The Gwadar-Xinjiang Pipeline is the only feasible project currently underway that provides an alternative to the Malacca Strait altogether and it seems that China is hedging on its success. However, Gwadar port is still under construction – with estimates ranging from 2025 to 2030 for completion – and so, until then, Beijing will try its best to acquire influence over the Malacca Strait at any costs. Expect more Chinese meddling in the Malay peninsula.

Be First to Comment