“It works, and it was meant for problems like Chicago: Stop and frisk,”

Speaking to an audience of law enforcement leaders in Orlando in early October, President Trump stated that Chicago police officers should bring back stop and frisk policies to reduce crime rates. To Trump, Chicago’s violent crime problem is “very easily fixable” — it could be solved if the CPD was “much tougher” on the people in the communities they serve. But what does it mean to be “much tougher”?

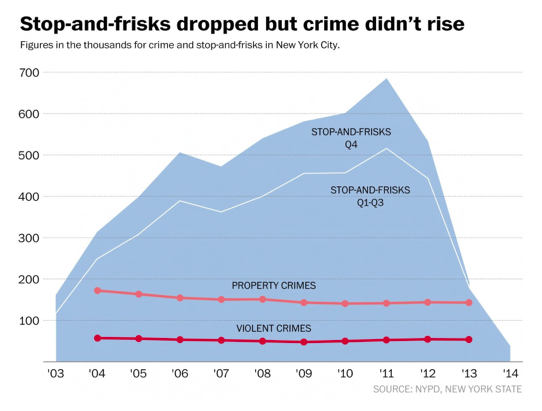

Stop and frisk policies are controversial because they have been proven to disproportionately affect minority groups, while studies show they provide no direct reduction in crime. “Stop, question, and frisk” policing methods drew national attention in 2013 when the Center for Constitutional Rights filed a federal class action lawsuit against the City of New York. The court decided in favor of Floyd: that the NYPD conducted these stops without reasonable suspicion, and that stop and frisk policies disproportionately affected people of color. Approximately 85 percent of those stopped at the time were Black and Latino, despite the fact that these two groups made up only 52 percent of New York City’s population. Thus, such policies were deemed unconstitutional, violating the Equal Protection Clause under the 14th Amendment. Although the city tried to appeal, it officially withdrew the effort in 2014 and began participating in the court ordered joint remedial process, in which a more inclusive group — community members, political leaders, the media, and law enforcement — is involved.

Considering the recent history of stop and frisk, Trump’s law enforcement policy suggestions are inherently controversial. From his perspective, however, the issue is simple. At the same rally in Orlando, Trump attempted to pit police against the media, arguing that news outlets do not report enough on the extent to which Americans admire law enforcement in their communities. President Trump pairs his law enforcement policy suggestions with constant praise and reverence for officers. Here, the issue of crime becomes a rhetorical tool, and how police policy and officer behavior each affect real communities is removed from the equation. From the viewpoint of the current administration, any attempt to critique law enforcement policy or behavior, no matter how valid, is counter-productive, anti-police. Yet, it is a near impossibility that Trump or former Attorney General Sessions are unaware that stop and frisk policies disproportionately affect minority groups. To Trump, “law and order” means the preservation of a specific social order, not the rule of law; that crime is not defined by any specific offense, but by the person who commits crimes.

Trump called it “disgraceful” that some politicians “escalate political attacks on our courageous police officers,” adding that, “politicians who spread this dangerous, anti-police sentiment make life easier for criminals and more dangerous for law-abiding citizens.”

With this, Trump suggests giving law enforcement officers, in a city where the police department has a long history of systemic mistreatment of minority groups and fraught community relations, more individual discretion and autonomy. In Chicago, violent crime rates and community relations with the police department are undoubtedly intertwined, and the CPD has a long way to go in terms of systemic police misconduct. Vox reports that a 2017 Justice Department investigation found that the Chicago Police Department “has tolerated racially discriminatory conduct that not only undermines police legitimacy, but also contributes to the pattern of unreasonable force.”

The shooting of Harith Augustus in July 2018 has squarely placed Chicago’s history of policing problems back in the public eye. The 37-year-old barber was shot while running into the street after being confronted by officers for, according to a spokesman for the department, “exhibiting characteristics of an armed person.” While he was, in fact, carrying a gun, there is no way the police officers could have known whether he was licensed or not when they stopped him. While there are still many questions about the shooting, protests erupted in Chicago’s South Shore within hours of Augustus’ death. During the demonstrations, community members shouted, “Who do you protect? Who do you serve?” These protests no doubt reflect the tensions brought about by the fact that Augustus is just the latest victim in a series of shootings in Chicago involving law enforcement over the past decade.

A New York Times study found that the CPD is relatively homogeneous when compared to the city’s demographic makeup of roughly equal parts white, black, and latino individuals. Despite several lawsuits between 1970 and 2000 that mandated the department to hire more minorities, the CPD is still comprised of over 50 percent white officers. This underscores the systemic race problem at work here, as raw statistics indicate that Chicago law enforcement officers are nearly 10 times more likely to use force against black residents than their white counterparts. Furthermore, in 2014 the ACLU found that despite only constituting a third of Chicago’s population, African Americans were 72 percent more likely to be targeted by stop and frisk procedures. Since law enforcement is given legitimacy in our democracy — as cops are meant to protect and serve the people — who police officers are matters as much as the policies they are instructed to carry out.

By suggesting policies that would give individual police officers more autonomy and discretion to exercise over their communities, the Trump administration is actually, counterintuitively, subverting the legitimacy and authority of law enforcement. Firstly, there is no clear and direct link between stop and frisk policies and reduced crime rates, which in Chicago — although high — have been declining for the past few years since stop and frisk was abandoned. The CPD reported in early October that the number of homicides has dropped from 762 in 2015, to 520 in the first nine months of 2017, and now to 419 in the same time period of 2018. The number of shootings is down 17 percent from 2017 as well.

Trump’s rhetoric supporting law enforcement is more than contrary to his suggested policies — in Chicago, they are actually antithetical to current, more effective reform efforts. Chicago has recently taken up a Consent Decree — a court-enforced settlement aimed at advancing institutional change. Many other cities around the country have enacted, or are in the process of drafting, Consent Decrees. On a fundamental level, these policies are meant to be enforceable: A federal judge must approve an independent monitor to measure the police department’s progress as specified by the Consent Decree itself. Issues addressed in the document include community policing, impartial policing, use of force, recruitment and hiring, and training reforms.

The point of such an agreement is to help ground reform efforts by making them measurable, and to keep law enforcement officers accountable for their behavior. Transparency is key. Think Progress argues that “transparency without data is meaningless, and accountability without transparency is impossible.” In other words, the current administration’s policies will only muddy the waters, which will inevitably inflame the same tensions it claims to want to subdue. For example, Trump and Sessions frame their objections to Chicago’s Consent Decree as a matter of administrative problems, arguing that these policies needlessly complicate a police officer’s ability to do their job. One of the provisions under the recent, lengthy agreement is that officers have to track instances in which they point their gun at people. Opponents of this provision also argue that it could lead officers to hesitate at critical moments, and thus put them at further risk. Dig deeper, however, and such an argument implies that accountability policies and high-quality police work are not compatible. According to Chicago Justice Project’s Tracy Siska, “the notion that such basic accountability will freeze cops in their tracks when they ought to be acting is familiar…. But…suggests the training itself is askew.” While a potential moment of hesitation is often spun at putting an officer at risk in the line of duty, isn’t a beat of critical thinking vital before they potentially point and fire a deadly weapon at someone?

Trump’s ‘solution’ to violent crime in Chicago actually highlights pre-existing, systemic problems, and would only aggravate them further. While it is too early to conclusively say if these efforts have directly caused a reduction in crime, reforms in Chicago, such as its Consent Decree, certainly coincide with reduced crime rates. Consent Decrees can be seen as more than formal legal mechanisms for reform efforts, rather, they demonstrate a recognition of soft power realities. If cops do not see a rule as legitimate, they will not be inclined to follow it, which could stall reform progress. Trump and Sessions may reject these agreements on the grounds that they inhibit the ability of law enforcement officers to do their jobs; more regulations means, to Trump, a decrease in the hard power of policing. Trump’s Nixon-esque views on “law and order” — i.e. proposing a reinstallment of stop and frisk policies — subverts the legitimacy, authority, and effectiveness of the very organizations he claims to support.

Featured Image Source: Politifact

Be First to Comment