I was in Montana on June 26th of 2015. I had been camping in Glacier National Park, enjoying summertime, being a tenth grader, not worrying about politics, adulthood, or being queer. Well, maybe that last thing wasn’t entirely worry-free, but June of 2015 wasn’t a bad time to start pondering my adolescent sexuality. Even in the heart of solid-red Montana, the mountain air felt celebratory that morning as every major news outlet announced their breaking headline: love was legal in all 50 states.

Prior to that fateful day, 13 states prohibited same-sex couples from marrying with laws challenged in Obergefell v. Hodges, an investigation of the constitutionality of state bans on same-sex marriage along with the refusal of states to recognize same-sex unions carried out legally in other jurisdictions. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court found that the 14th Amendment provided protection for same-sex couples on both of these questions, striking down marriage prohibitions and ensuring recognition of homosexual civil unions.

The Complicated Consequences of Obergefell

In the decades preceding Obergefell, achieving the right to marry occupied the center stage of mainstream gay rights advocates’ agendas. Denying homosexual couples marriage was an incredibly blatant manifestation of cultural and legal homophobia, evidence of a nation committed to antiquated, highly exclusive definitions of partnership. Now, in the years following Obergefell, protecting its guarantee has become just as central to LGBTQ+ activism as gaining this liberty was in the first place. With the arrival of the Trump Administration, the appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, First Amendment-based challenges to Obergefell, and legislative backlash on the state level, protecting marriage necessitates vigilance on all fronts.

Fear of Obergefell being threatened, or worse, overturned, in the face of conservative, originalist Supreme Court justices and an increasingly polarized nation is understandable. The fight for marriage was long and hard, a path paved by gay activists over the past century with immense labor; the fight took place in the courts, but also involved the bodies of queer folks themselves––those committed to creating a more inclusive civil society regardless of the costs. While there are many ways for the courts and legislature, both federal and state, to chip away at the guarantees of Obergefell, it is ultimately unlikely that the decision is in any real danger of being overturned. However, evaluating the status and effects of Obergefell three years later is a salient task: this ruling has not necessarily been as simple, or as entirely-positive (read: uncomplicated) as we tend to think.

Thinking about LGBTQ+ rights in the Trump era asks us to go beyond praising the right to marry as something ensured, but to also go beyond the notion that this right, safe or unsafe, is enough. It’s time to think about who has been left out of LGBTQ+ gains, as well as what marriage equality really means. Who is being made equal to who? Whose bodies are admitted entry into this space of supposed equality? What other issues are silenced or ignored when our collective, activist energy is spent protecting marriage?

Don’t Get Me Wrong, Obergefell has Done a Lot of Good

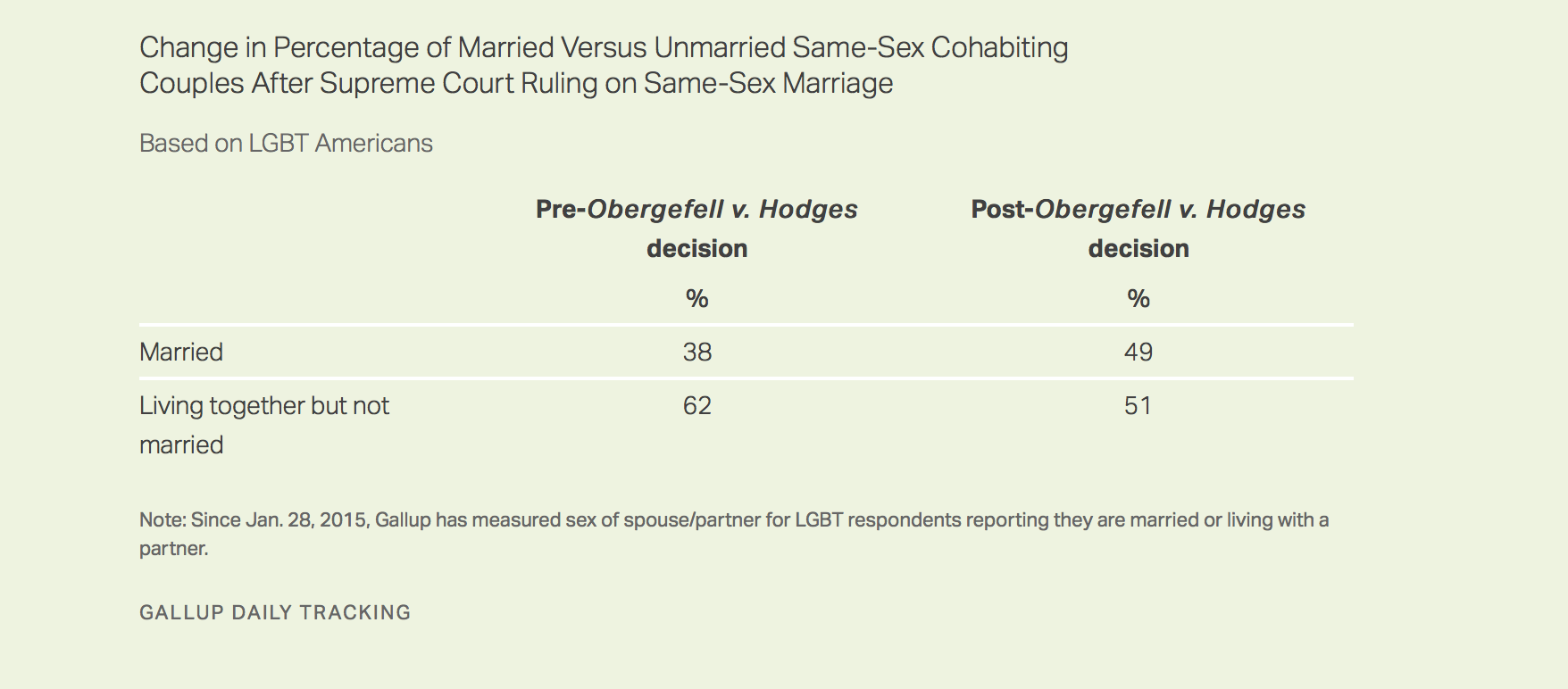

First thing first: this is not to say that Obergefell v. Hodges shouldn’t be hailed as a victory for same-sex couples. As of June 2016, one-year post-Obergefell, nearly half of all same-sex couples who lived together were married, an 11% increase in 12 months. This increase didn’t just come from couples marrying in states with newly overturned prohibitions: marriage rates increased among same-sex couples across the nation, including those in states which had no prior ban. The general increase in marriage among same-sex couples can be seen as signaling an increased acceptance, and enjoyment, of homosexual unions post-Obergefell.

Moreover, increased marriage rates directly correlate to statistics concerning adoption. As a couple, it is far easier to adopt a child once married; few states encourage joint adoption by unmarried partners. Greater ease in the ability of same-sex couples to adopt children, if they so desire, can be seen as a positive gain; it endorses and empowers same-sex couples in their capacity to start families, a key aspect of our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness under the Constitution.

Not only is increased opportunity to adopt a positive for homosexual couples looking for domestic equality alongside marriage equality, but for children in need of homes. Same-sex couples are 10 times more likely than married, different-sex couples to adopt children. It’s simple math: more married same-sex couples equals more children adopted.

As same-sex couples are more able to build families, their relationships and lifestyles become increasingly visible. Turning a practice into law facilitates greater awareness of it within the realm of public discourse. With more conversation surrounding non-traditional (non-straight) partnerships as a result of Obergefell alongside an increased rate of same-sex marriage, it is reasonable to conclude that the decision normalized, or further destigmatized, homosexual couples. This normalization manifests cognitively: we are more able to picture same-sex partners as fitting into the picture of American family life, heightening their public visibility within the discourse surrounding acceptable family constructions.

Gorsuch v. Gays

With these positives of Obergefell in mind, it is not hard to see why protecting the decision would occupy a central role in LGBTQ+ activism during a good year, let alone a tough one. This past year, however, has been far from a good one. In turn, the need to protect Obergefell has escalated in urgency. On April 7th of 2017, Neil Gorsuch––Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nomination to fill the seat of Antonin Scalia––was confirmed by the Senate. While this confirmation was riddled with controversy, Gorsuch’s originalist interpretative lens alone was enough to rile up Democrats. Even before Gorsuch’s confirmation, the new Justice’s opinions in cases concerning LGBTQ+ rights were called out by liberal opponents of the Trump Administration as evidence of a greater effort to undermine civil gains. Nearly every news source reporting on the issue mentioned marriage equality as an area to which Gorsuch posed a threat.

While perhaps sensationalist in manifestation, such fears were not unfounded. The Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law was one of many organizations to document and examine the LGBTQ+ rights record of Gorsuch during his confirmation process. Their findings, from a queer perspective, were dismal. On the 10th Circuit, Gorsuch repeatedly displayed a distaste for extending constitutional rights to transgender people, most prominently in the cases Druley v. Patton and Kastl v. Maricopa County Community College District. These past opinions set the tone for Neil Gorsuch, one which put LGBTQ+ and civil rights advocates on high alert.

In the months since his confirmation, such fears have been thus far validated. In June of 2017, Gorsuch chose to dissent in Pavan v. Smith. The story goes as follows. Terrah Pavan, partner of Marisa Pavan, gave birth to a child the Pavans intended to raise together, as partners and parents. The state of Arkansas, however, refused to list Marisa Pavan as a legal guardian of her new child on the birth certificate, claiming that she was unable to prove “biological parentage.” While the SCOTUS reversed this decision due to the state’s “disparate treatment” of a same-sex couple, something explicitly prohibited under Obergefell, Gorsuch chose to dissent, providing groundwork for lower courts to challenge same-sex rights on the basis of biological justifications. Dissents, along with majority opinions, serve as powerful precedent for judges nationwide, establishing new (or in this case, old) frameworks for evaluating constitutional issues. While Gorsuch alone cannot dismantle the promises of Obergefell, he has the ability to give language and validity to its opposition.

Backlash to Obergefell

Conservative backlash never follows too far behind any liberal gain. In the three years following Obergefell, even before the arrival of Gorsuch to the highest court in the land, such backlash has complicated the effects of what is usually perceived as a net-positive civil rights gain. This is most aptly represented with the 2015 reintroduction of the First Amendment Defense Act (FADA), brought before Congress just days before the Obergefell decision was handed down. One of Donald Trump’s key campaign promises was to sign this act if passed through Congress, and it represents the missing-linchpin of most anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in our country today. If passed, the FADA would protect discrimination against same-sex couples, a demographic it explicitly cites, under the First Amendment’s guarantee to Religious Freedom. The FADA would allow businesses to sue the federal government for reprimanding them for discriminatory practices, halting any government sanctioned attempts to prevent discrimination. Effectively, the FADA would render Obergefell toothless, gutting the decision of any power to justify enforcement of its promises.

Even without the First Amendment Defense Act, businesses and states alike have already staked their claim on the First Amendment as their ticket out of demonstrating equal treatment to all couples regardless of sexual orientation. Look no further than the recent Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission case. While still pending a decision, the refusal of the Masterpiece Cakeshop in Colorado to entertain same-sex patronage––in this case, that of Charlie Craig and David Mullins––embodies the state and individual level resistance to Obergefell. The extent of the First Amendment in protecting Speech and Free Exercise in accordance with religious beliefs will be tested with the Masterpiece decision, but even now this argument provides an apt representation of the tension between federal protections and individual beliefs.

The discretion of judges has also provided a form of backlash to the guarantees of Obergefell. In Oregon, a judge was accused of developing a system where clerks were asked to investigate couples pursuing marriage licenses. If a couple was found to be homosexual, the clerk was instructed to inform them that the judge simply was not available to see them. Oregon is a recent example of such a discretionary scheme, but it’s certainly not the only state in which courts are involved in homophobic (and painfully transparent) forms of avoiding the law.

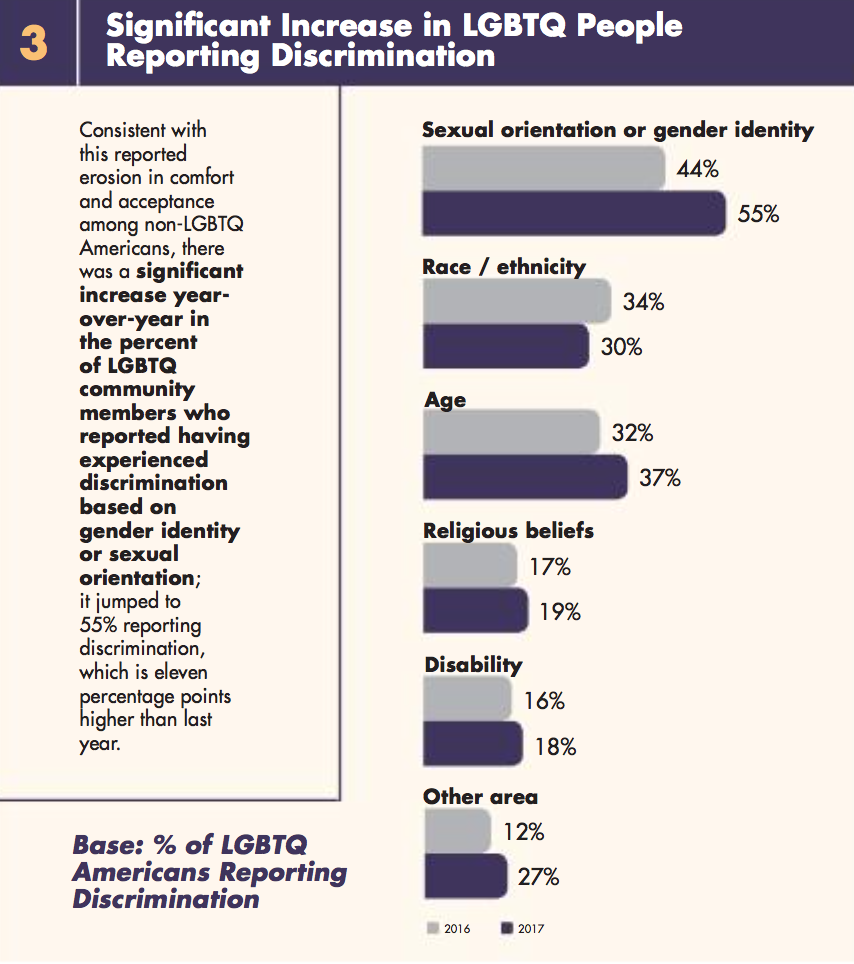

Along with ignoring or dodging the law, some states have taken it upon themselves to pass their own, subsequent legislation aiming to render Obergefell ineffective. According to the GLAAD 2018 Accelerating Acceptance Report, an annual publication on the status of LGBTQ+ acceptance nationwide, there has been a proliferation of anti-LGBTQ+ state legislation since the Obergefell decision. This is tangible evidence that the opinion of Jack C. Phillips, owner of Colorado’s Masterpiece Cakeshop, is shared by the legislature, not just individuals. Since 2015, there has been an increase in overall experiences of LGBTQ+ discrimination, something which correlates with 2016 FBI data demonstrating a five percent increase in hate crimes against LGBTQ+ populations between 2015 and 2016. When we read “since 2015,” we have no choice but to read “since Obergefell.” While it would be far-reaching to claim that the Obergefell decision directly and solely led to a proliferation of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and a rise in hate crimes against the queer community, it would be just as naïve to deny the power of the ruling in spurring opposition. Obergefell touched something in the polity that has everything to do with values, supposedly American values, values which tangle themselves at the intersection of faith, patriotism, identity, tradition, and moral judgment. None of this is to say that Obergefell has had a net-negative effect on same-sex couples, nor that it was ruled in err, but rather to acknowledge the complicated and oftentimes counterintuitive impacts of liberal gains.

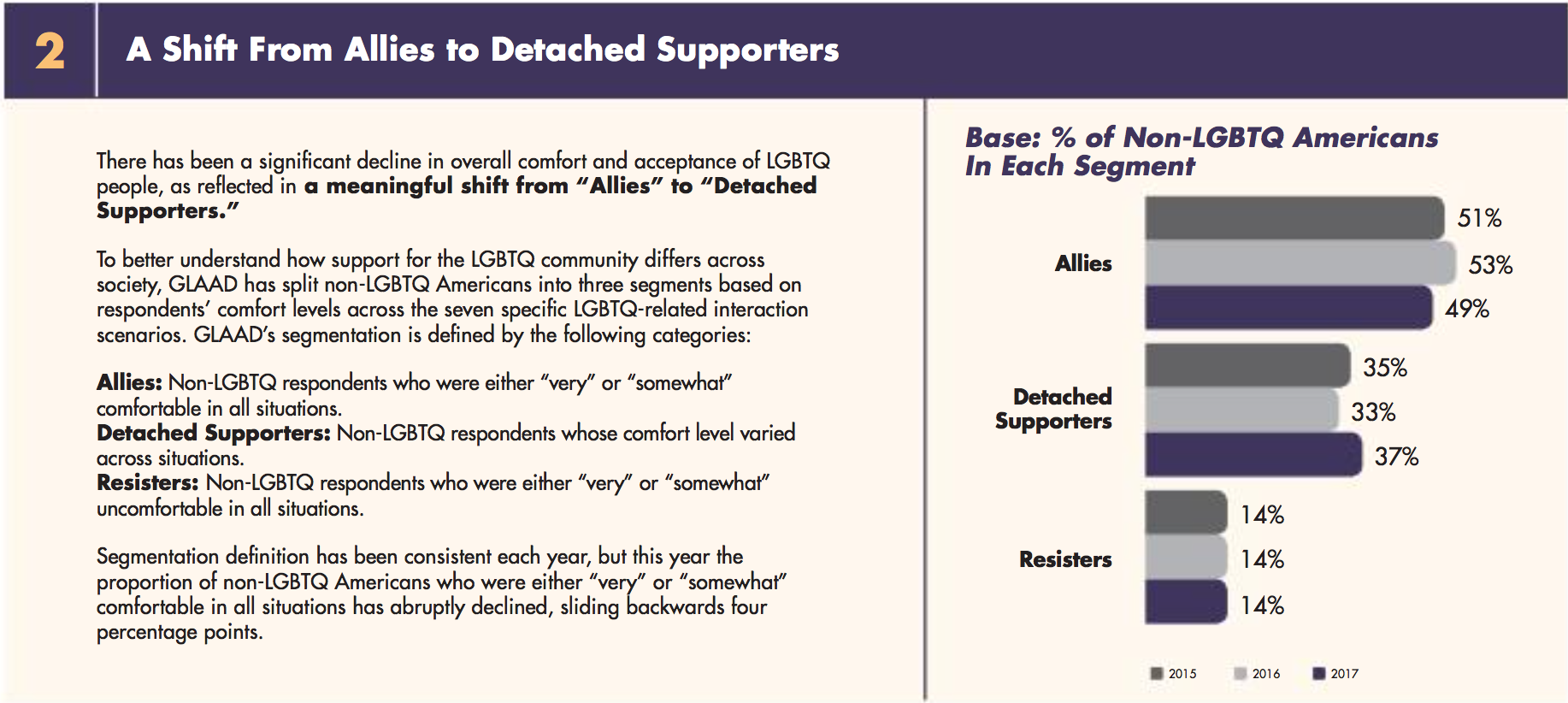

When we focus on the positives of marriage equality––and the positives alone––we allow ourselves to be placated. The 2018 GLAAD report includes a startling study, one which outlines the shift in allies of LGBTQ+ rights to detached supporters of said rights. Same-sex marriage was paraded as a panacea of discrimination as if only a wedding ring stood between the LGBTQ+ community and full societal acceptance of queer forms of love. The pervading attitude of “well, we got marriage, now we can check LGBTQ+ rights off the list” is one which blinds us to these continuous discriminations: the rise in hate crimes, the violent legislation, the health care access barriers placed in front of queer citizens, the targeting of LGBTQ+ communities by law enforcement, the high rates of LGBTQ+ youth homelessness, and all other ongoing obstacles and injustices faced by non-heterosexual individuals. When marriage, and furthermore, the protection of the right to marry, becomes the end-all-be-all of queer rights, we miss things. We overlook realities, a form of omission which has a body count.

LOVE IS LOVE, but is it?

Thinking critically about marriage equality entails two key questions: first, who are the beneficiaries of this right, and second, who is left out? To answer these questions, we first must unpack the phrase itself. Marriage equality comes with its own set of connotations and limitations, the first of which is entirely linguistic. The word equality necessitates a baseline; something is being made equal to something else. In the case of marriage, we can presume that same-sex couples, those historically barred from the institution of marriage, are being brought up to the baseline represented by heterosexual couples, those for whom marriage was constructed. Once we accept this premise, the notion of marriage equality problematizes itself. To be made equal to is, on one level, to be made the same as, or at least to adequately mimic. This brings us back to the normalizing effect of same-sex marriage. While such normalization makes visible same-sex couples, it only makes visible certain types of same-sex couples: those who can perform straight, fitting into the heterosexually-developed institution of marriage.

For those who desire it, marriage is certainly a fundamental right. However, to act as though marriage is the “solution for the problems that most queer people face” ignores the diversity and multiplicity of queerness. In her article Beyond Marriage, Lisa Duggan argues that “marriage does not provide full equality… or expansively reimagined forms of kinship that reflect our actual lives.” If we recall the marriage equality slogan, LOVE IS LOVE, such a comment feels contextually apt. To say LOVE IS LOVE is a way to communicate to queer couples, even if subtly, that their love is acceptable only if it looks as much like the love of their heterosexual counterparts as possible. If kinship includes a house, monogamy, a desire to raise children, and a regular income, perhaps it can be considered tolerable. Queer love is okay as long as it is as close to straight love as possible; queer love is okay as long as it does everything it can to make us forget it is queer.

What about queer couples and individuals, love interests and chosen families, who are, by the quality of their queerness, operating outside of these normalizing forces? Has a focus on marriage really made us all more equal by emphasizing similarities between types of love, or rather, has it made clear the lack of acceptable types of love available to us in the first place? If you cannot fit into the financially stable, marriageable form of intimacy deemed socially acceptable, you do not have a place in this new age of equality. If you are uncomfortable or unable––due to class, race, ability, gender, or specific sexual preferences––to perform within this heterosexual framework, there is no space here for your body.

A New Gay Agenda

With this in mind, the future of LGBTQ+ rights seems clear. Complicated and extensive, sure, but also clear. Protecting Obergefell from the likes of Neil Gorsuch and the Trump Administration’s crusade against civil rights is a noble task, but it cannot take precedence over addressing problems of the queer community at large. Homeless queer kids live in our streets; transgender people are denied health care; hate crime rates continue to rise. All counterarguments to this issue hinge upon the notion that what we have now is as good as it gets, that asking for anything beyond marriage, beyond equality, beyond sameness, would be greedy (read: would make us uncomfortable). The suggestion that hate crimes are inevitable, or that discrimination is natural, or that de jure legal gains are all we can really hope for, are ways to placate ourselves, to avoid doing the labor of imagining, and working to manifest, futures beyond our status quo.

We must look, as Duggan implores us, beyond marriage. This starts with enforcing mandatory hate crime reporting in all states, creating queer inclusive (and positive!) sex education in schools, fighting back against legislation and court cases which aim to undermine queer gains, and acknowledging the intersection of queer rights with the rights of undocumented people, people of color, disabled people, and all other non-normative bodies seeking space and voice within society. Marriage is a right we are entitled to, and Obergefell reminds us of that. To settle for marriage as the finish line for queer equity, however, is a disservice to our community. Equal is not enough, nor is it synonymous with tolerance, respect, or more potently, celebration: we should aim to exalt difference, endorsing a culture which protects diversity, rather than one which aims to render everyone the same without contemplating who is erased in the process.

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Be First to Comment