The United States is obsessed with age. Particularly the age of children; we track their development from fetal life forms to parents themselves, careful to never forget what restrictions must be imposed upon them as they grow. The notion of “underage,” while perhaps bothersome in our adolescent days, affirms us in our adulthood. It feels good to grow into privileges; new and improved allowances always peering at us from the horizon.

Before privileges, however, come restrictions. These restrictions, imposed through law onto and over the lives of children, typically stem from an ideology of protection. Children are our future and are continuously pointed to as such within the realm of policymaking. The problem with this tendency –– to turn the child into a metaphor –– arises when the urge to protect the child of the future manifests through controlling the literal child of the present: denying children autonomy over their bodies and reducing them to not-fully-human rather than just younger ones among us.

The arbitrary nature of these restrictions, rooted in age-based development conceptions, becomes most visible through a state-by-state examination of law. If we accept the notion that some privileges, for example, the ability to marry, should only be enjoyed at a certain age, one determined via widespread societal agreement regarding stages of maturity and responsibility, then the minimum marriageable age must be consistent across all 50 states. Right? While that would be logical, it is not the case. Different states have different age floors for marriage, and consistency cannot even be found within states themselves. In most states, judges have the ability to rule, on a case-by-case basis, whether or not they will allow minors to marry, even if the child in question is below the state’s technical minimum marriageable age. As of 2017, 27 states have no functional minimum marriageable age: through judge and parental based exceptions, children of any age are able to marry. Here, we begin to understand the true problem with age-based legal restrictions. Adults, both in forming and undermining the law, are placed in a privileged position over the bodies and lives of young people.

I am not here to argue that children always know what is best for themselves. Not at all. Rather, I see an urgent need to recognize the way we –– U.S. lawmakers, judges, parents, adult citizens –– manage children. When laws are written, or not written, to protect children, what definition of protection are we ascribing to? Whose values are we perpetuating? Where is the child’s voice in all of this; who claims to speak on their behalf?

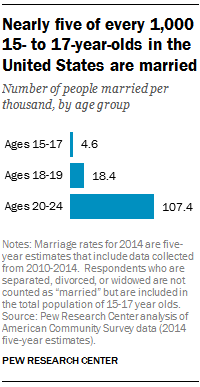

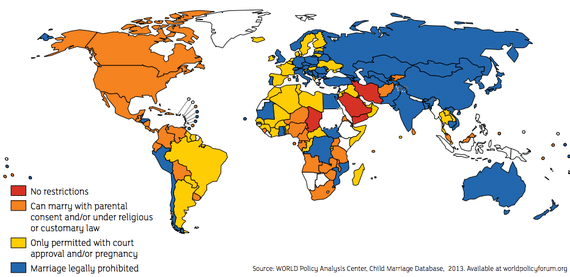

In the United States, we tend to associate the issue of child marriage with the so-called developing world; images of arranged or forced marriages of young girls to older men are often circulated by western feminists and NGOs, hoping to drum up support and dollar-donations towards their crusade for the liberation of the Third World Woman. And yet, talk about arranged marriages overseas not only lacks cultural relativism but serves to turn our attention away from the problems and hypocrisies crowding our own American backyard. From 2000 to 2015, over 207,000 American children, under 18 years of age, were married. Chances are, due to a lack of honest reporting and comprehensive investigation, this number is conservative. Part of the widespread denial (a key facet of American exceptionalism) of our minor-marriage problem involves a lack of reliable data and research on the issue. Ignorance is bliss, or at the very least it’s cheap. By turning a blind eye and choosing not to study the issue, lawmakers can save themselves the time and money of writing and implementing new policies to curtail the coercion of children into civil unions by judges and parents.

Coercion is a charged word, and I mean it as such. Reasons cited by judges and parents for endorsing (or enforcing) these marriages range from religious justifications to a desire to cover up pregnancy out of wedlock, including that of sexual assault. Children who marry before adulthood –– children whose lives have been arbitrated by the agency-robbing decisions of their guardians –– are more likely to experience intimate partner violence, worsened physical health due to high-stress levels, sexually transmitted diseases, and are 50% more likely to drop out of school prematurely than unmarried youth. Young girls, whether they are 14 or nearly (though not quite) 18, are at a particularly high risk in these situations. Anyone who is legally defined as a child, and thus lacking signatory status, is unable to file documents that are of critical value to most other couples entering marriage. For example, the safety net of divorce paperwork. How is it that children can get married but cannot file for divorce? Beyond barriers to legally ending the marriage, the process of exiting the relationship itself, unlike the act of entering it, is made extremely difficult for minors. Many domestic violence shelters only accept adults, a status defined as over 18, thus preventing minor-brides from seeking support should they need it. Without the ability to divorce their partner or the ability to seek refuge in a shelter, young women are effectively trapped into their relationship, one which is already three times more likely to include physical abuse towards the female spouse than marriages of those 21 years of age or older.

Nationwide, there is no mechanism in place to ensure that coercive and non-consensual circumstances stay out of such marriages: how do you legally regulate what is already an exception to regulation? While some states have made major strides towards curtailing this issue, the effort has yet to be reflected by the American legislature at large.

In the case of marriage, age is wielded as a generalized means of keeping children under (think subordinated, controlled, handled) the law as wielded by adults, rather than the law as it is written. Under 18 becomes synonymous with under everyone else, forced to reside outside even those protections specifically meant to aid the demographic. This is not just a handling of the child as a legal entity, prematurely ushered into a marriage license, but as a sexual entity as well. How is it that in some states, the legal marriageable age is lower than that of consent to sexual intercourse? Take California, a state typically hailed as a beacon for liberal progress, and where there is no minimum age for marriage when parental and judge exceptions are accounted for. By contrast, the minimum age for consent to sex is a hard 18. On one hand, the legislature has deemed consent to sex a concrete category, one in which no child may participate –– legally speaking –– under any circumstances. Marriage, on the other hand, is nothing but one big loophole. What do these rules, while seemingly oxymoronic, have in common? Both use an arbitrary understanding of age to keep children from assuming agency. When it comes to sex, no child has the right to assert their voice in the realm of consent. The same goes for marriage: while minors are able to get married, it is not of their own accord. Consent is given or denied on their behalf through a process that does not mandate nor invite their input. In both of these legal constructions, age is used to keep children out of decisions concerning their bodies and futures.

This should be confusing to you. How are we so paranoid about underage sex, and yet so relaxed about child marriage? Laws surrounding consent to sex (concrete) and consent to marriage (unbelievably flexible) reflect the shared societal notion that adults always know what is best for children, one that assumes the primary goal of government, in terms of regulating the child, is to protect them. Parents and lawmakers like the idea that marriage can be a quick fix to a messy situation, a way to avoid dealing with complicated issues surrounding abuse, childbearing, and yes, even sex itself. The idea of protection quickly begins to have more to do with comfort than anything else: sex between unmarried children, even if pleasurable, safe, and emotionally consensual, goes against our nation’s still predominantly puritanical values. Marriage, by contrast, is the pinnacle of that same puritan value system, even if those involved have been denied a say in the matter.

Laws should work for the people they aim to protect, not against them. We’ve already gone over the harms of child marriage and the coercive reasoning maintained by courts and families for allowing it to proceed. What about the harms of using arbitrarily drawn age restrictions for consent to sex (which, like marriage, vary from state to state)? In marriage laws, children are left to passively navigate legality by virtue of total government and guardian control. When it comes to sex, their role is just as passive: after nearly two decades of living outside the world of legal consent, one morning a child wakes up and is able to say an affirmative yes to intercourse. What changed?

We need to reimagine and reform the mode of assuming consent we currently ascribe to. Turning 18 (or 16, or 17, depending on your state of residency) is not the same thing as being educated about sex; consent should be about taking an active role in safety, respect, and health. What I’m asking us to imagine together is a future which puts an end to child passivity, both invited and forced. Consent should be about knowledge, not about a birthday party.

A nation that values the sexual agency of the child looks, perhaps, like this: the ability to consent to sex is linked to education rather than age –– think sex ed, but competent, comprehensive, and standardized. If all American high school seniors (per se) were mandated to take a course on healthy sex and informed consent, a course which culminated in a test (one that could be passed or failed), the assumption of the ability to consent would be an active one, a knowledge affirming one. At first glance, this idea may seem audacious, or at the very least, unrealistic: taking a test, in a public school, on consent? Linking sex, a notoriously hushed and relentlessly tabooed act, to a proficiency exam? The thing is, we already do this with a myriad of other privileges. For starters, driving. When it comes to operating a vehicle, we hold the collective expectation that our fellow drivers know what they are doing before they get behind the wheel alone. For this reason, teenagers go through driver’s education, permitting, and testing prior to earning a license. Why not a license for sexual consent? Why not link sexual agency to something more meaningful than age, and age alone?

This move towards empowerment through knowledge should be present in our re-writing of marriage laws as well. We need a mechanism for determining whether abuse or coercion is at play before marriage, between minors or otherwise. This begins with heightened awareness and acknowledgment of the issue, a first step we have already taken, just now, together. The second, most critical step involves valuing the voice of children. We should stand with the states that have already begun amending their laws to prevent child marriage but must stay critical and demanding. No marriage should be forced, no child’s voice should be devalued by the quality of their age. We need both a solidified, consistent age floor across the board –– not one which can be moved at the will of adults arbitrarily –– and a process that includes the insight of the participants themselves.

Featured Image Source: Alyssa Plese, BPR Design Team

Be First to Comment