A woman is sentenced to prison in Oklahoma. Her crime is nonviolent––methamphetamine possession, theft–– and she finds herself serving her sentence in the Mabel Bassett Correctional Center (MBCC) in McLoud, the largest women’s prison facility in the state. She is one of 1,139 minimum and medium security level inmates here but is also part of another demographic: that of Oklahoma’s pregnant inmates, all of whom are housed in this sorely overcrowded facility. She has been transported to medical visits periodically since arriving. During these trips, she is handcuffed.

Her pregnancy was known upon her conviction as well as sentencing––it is why she was placed in MBCC despite its overpopulation––so, her due date should come as no surprise to the medical officials and supervisors of the prison. Everything that happens from this point on is according to plan. No one is caught off guard by the needs of a pregnant woman in a prison which sees upwards of 30 births a year. Her needs are known, and they are ignored. They are ignored as she finds herself fully shackled, a process which includes the application of leg irons, a waist chain, and handcuffs, and is brought to the hospital. Here, as she enters labor, the restraints are not removed but instead adjusted; she is shackled to the bed to further ensure her immobility, to remind her that even now, her primary identity is not a mother, but a threat.

After the birth, she is asked not to breastfeed her child. She is allowed to spend 48 hours with the newborn before being returned to prison. In transit, she is, once again, shackled. She is lucky: her labor was uncomplicated. If it had been, the restraints would have prevented doctors from immediately assisting (Links to Paywall) herself and her baby. New to this world, criminal by association. Even in this best-case, status-quo scenario, she is left with cuts and bruises on her ankles and abdomen. They will take weeks to heal.

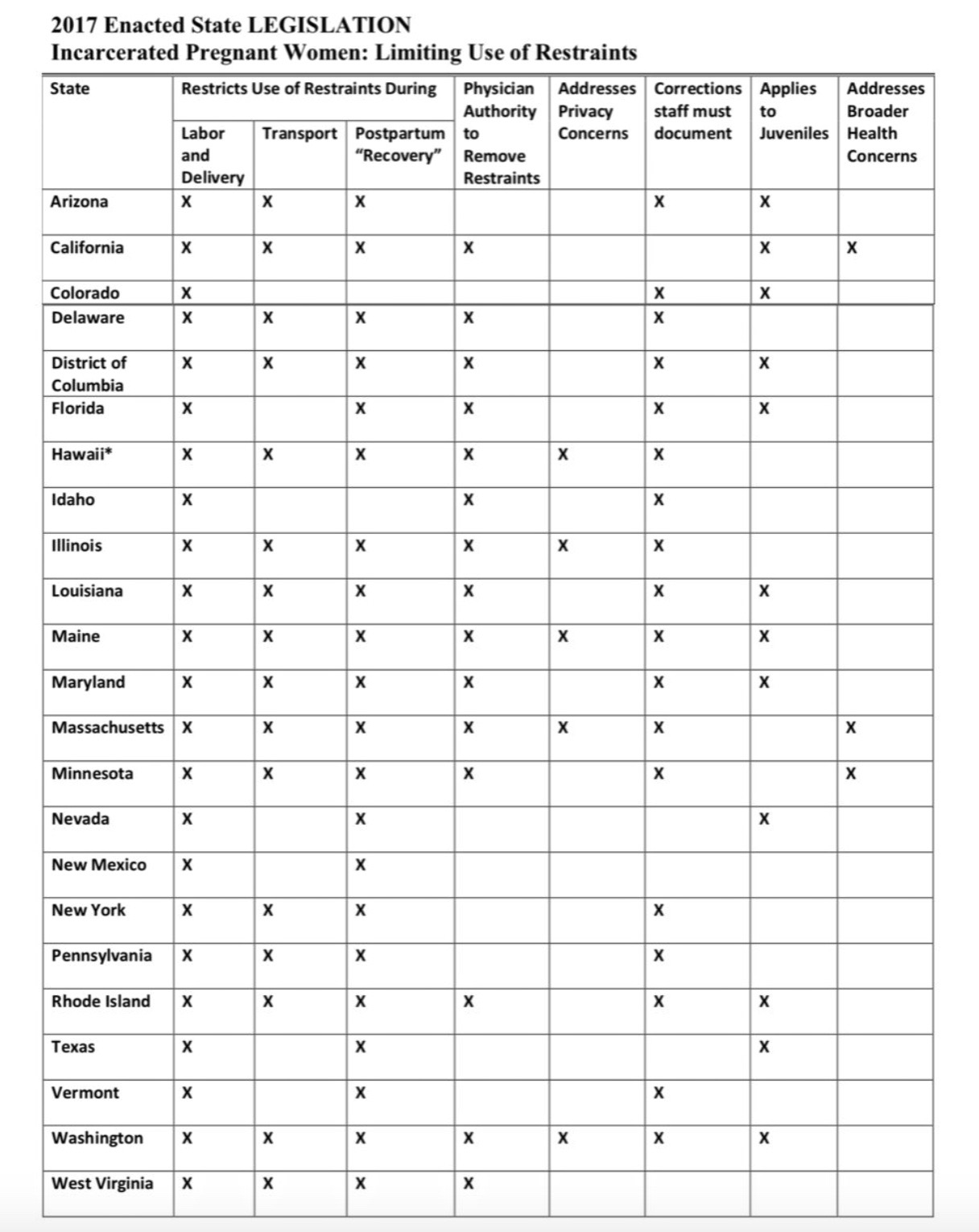

This is a story shared by pregnant prisoners throughout Oklahoma and the United States at large. MBCC’s practices present an especially poignant case study of the shackling of inmates during labor, but it is not necessarily unique. As of 2017, twenty-three states have laws prohibiting the use of restraints on mothers, leaving the majority of states with no legal prohibition on the practice. Oklahoma is one of these states. This is not to say that Oklahoma’s policies encourage the abuse of pregnant inmates. In fact, Oklahoma’s Security Standards for Transportation of Inmates states that “[o]nce it is determined by medical services that an inmate is pregnant, the inmate will be transported without restraints unless an Authorization to Apply Restraints to a Pregnant Inmate… has been approved.” While such a standard may not be bonafide law, it seems to be clearly discouraging of shackling, even condemning of it. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has echoed this same sentiment since 2008, in which it updated its policy to explicitly prohibit the restraining of an inmate both during and after labor unless they present an “immediate, serious threat” to themselves or those around them. And yet, pregnant inmates are still shackled in Oklahoma; mothers are still shackled across the country. How could this be?

The problem here is one of oversight. Regulations, and even laws in states which have them, are enforced by human beings. Legal restrictions and policy proposals, such as the 2017 Dignity Act, that aim to restrict violence against pregnant inmates all run into the central issue of prison facility discretion, something no single entity can adequately oversee in a structure as vast as the state prison system. If the prison itself is what’s broken, where do we go from there? While successful incarceration alternatives do exist today, most states are either reluctant to propose (and attempt to convince the public of) sweeping changes to the age-old prison system, or are too financially strapped, or both, to seriously consider investing in such programs over more standard, seemingly-pragmatic, regulatory solutions.

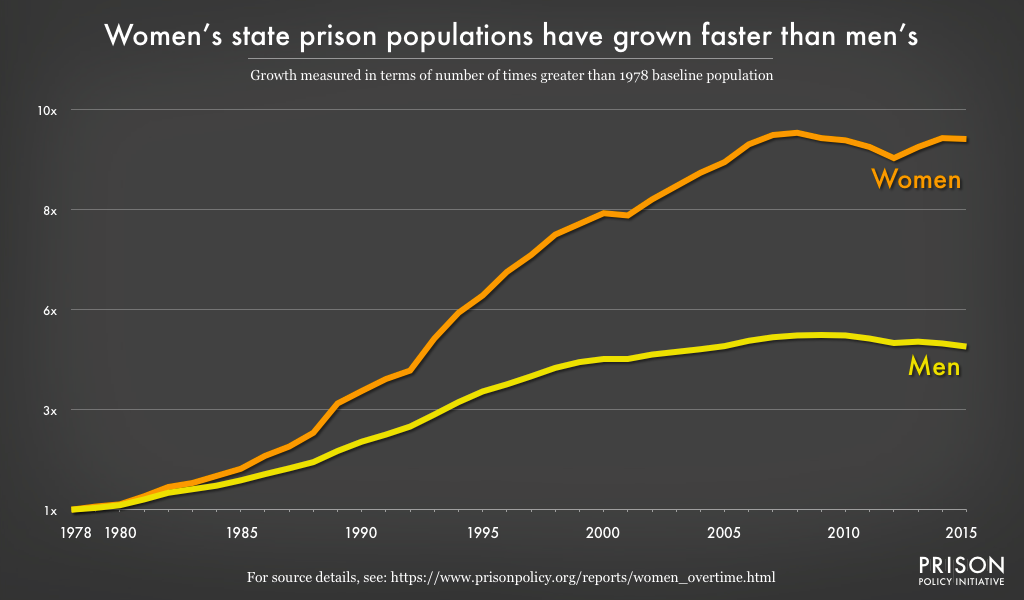

In a prolonged moment of mass incarceration in which the population of women in state prisons has seen a startling 834% increase over the last forty years, the plight of pregnant inmates cannot be left out of the criminal justice conversation. As seen in Oklahoma, it is not enough to have policies and provisions which condemn the practice of shackling. Such policies, even that of the BOP, are suggestions at best, often discarded under the discretionary authority of staff and officers who feel that they have “reasonable grounds” to impose restraints on pregnant inmates. This takes us back to the BOP’s convenient disclaimer in their anti-shackling policy: it is at the discretion of the Captain present to determine if the inmate poses an “immediate, serious threat.” It would take a truly brilliant criminal mind to plan an elaborate escape plan mid-labor, but the BOP seems to think such a caveat is critical. It may seem harmless, even necessary, to leave a loophole open for extreme circumstances. Like all loopholes, however, this one has widened with time. Once someone is labeled as criminal, the material needed to label them as a “serious threat” seems to write itself. To make matters worse, the consequences for neglecting to follow state policy prohibiting the abuse of pregnant women are so few and far between that there is little incentive for officers to abide by them. Inmates often do not file lawsuits due to a fear of retribution in the form of reduced visitation rights––an especially potent threat to a new mother––or due to the bureaucratic hoops associated with filing a federal civil rights case, hoops which include a $350 fine. Oftentimes, the very real fear of simply being ignored is enough to discourage legal action. It is easy for the voices of the incarcerated to be lost in the shuffle of bureaucracy when their lives have been reduced to Department of Corrections paperwork.

As violent and neglect-filled as this situation may seem, not all entities are ignorant to the treatment of incarcerated mothers. For starters, in 2010 the United Nations adopted the UN Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules), declaring that “instruments of restraint shall never be used on women during labour, during birth and immediately after birth” regardless of circumstance. The language is not broad here, as it was in the Oklahoma policy. It is strong, clearly denouncing the practice.

Now, trailing seven years behind the humane treatment practices advocated by the Bangkok Rules, the U.S. Senate has stepped up with a proposal of its own. In 2017, Cory Booker (D-NJ) introduced SB 1524: Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act. Cosponsored by other big-name liberal senators, including Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Kamala Harris (D-CA), the Dignity Act is no small order. The legislation calls for a strict prohibition on shackling of pregnant prisoners nationwide, free tampon and health items in prison facilities, limitations on the punitive segregation of inmates, and more. Booker goes as far to acknowledge the needlessly punitive nature of prison practices towards mothers. “We do unnecessarily harsh things that are not necessary for public safety, but really [just] punish women and punish their families as a whole,” said Booker to the Huffington Post. People in power are speaking up, and loudly.

If passed into law, it is easy to perceive the Dignity Act as the long-awaited answer to the maltreatment of pregnant prisoners. In many ways, it will be: the central issue of state ambivalence towards generating effective policies concerning shackling will be turned instead to the federal government. However, even the Dignity Act cannot be taken without a grain of salt. With an issue as silenced and pervasive as restraining and abusing pregnant prisoners, can one law really, truly be a panacea?

In evaluating the Dignity Act, looking towards the laws of the twenty-three states which have passed legislation to prevent shackling is critical. Take, for example, California, an early champion of anti-shackling measures. In 2012, California updated its Penal Code (section 3407) to ban the most dangerous of restraints from being used on pregnant inmates with the passage of AB 2530. Despite this statewide victory, one which did lead to a general betterment of the status of incarcerated women, the Legal Services for Prisoners with Children found, in a 2017 study, that ten counties in California remained non-compliant with the current law.

California, along with the rest of the country, is committed to a type of prison reform which hinges upon imposing requirements and regulations onto our preexisting system, a method which fails to dig down to the root of the issue. Whether in Oklahoma or California, anti-shackling law or no anti-shackling law, the environment of prison lends itself to the oppression of inmates––particularly of vulnerable demographics, such as that of mothers. There is no degree of oversight in the modern prison which could eliminate the use of these practices entirely; abuse is the manifestation of an always-unequal power dynamic between prisoner and state. If both policy and law are inadequate at addressing this epidemic in the long-term, what are we left with? If future legislation is bound to fall prey to the ineptitudes of state-level enforcement, how do we proceed?

Picture this: no prison (for mothers) at all. Thanks to alternatives to incarceration, this idea is more than a figment of the imagination. Let’s go back to Oklahoma. Women in Recovery (2017) and ReMerge (2011) are two examples of nontraditional, community-based approaches to helping women with children seek a better life while serving their sentences. Through non-government entities under government supervision, nonviolent female offenders with young children can voluntarily apply, or be recommended, to live in alternative programs, each geared toward addressing substance issues as well as parent-child bonding. The opportunity for mothers and children to remain close in their early years as a family reduces recidivism across the board, in both prison nurseries and diversion programs. ReMerge goes the extra mile to address the issue of soon-to-be mothers as well, giving priority selection to pregnant inmates.

These programs exist in many states––with high success rates in lowering overall prison populations, cutting costs, and reducing recidivism––including California, New York, and more. However, the amount, and type, of women these facilities can serve is extremely narrow. In California, the incarceration alternative program Prototypes has only twenty-four beds to its name at any given time, and the requirements to qualify are both difficult to find on one’s own and quite specific. Not all know of this option, and not all who seek it out will be granted entry.

These programs are not perfect: due to their private management, issues of neglect and failure to meet health and safety standards have arisen at many facilities, including the previously mentioned Prototypes. These shortcomings, however, can be seen as stemming from the general negligence of both the state and federal government toward alternative-to-prison programs. For these programs to work in the long term, money, time, and energy must be allotted to them, rather than towards more prison-regulating legislation. Laws will, at the end of the day, be ignored or bent beyond recognition by guards who have been socialized to see inmates as burdensome property rather than as people.

Thinking beyond incarceration is not easy; it asks us to reject the carceral framework of our society’s construction in a fundamental way. While some would argue for an end to incarceration entirely, I simply ask us to think of the women in McLoud, Oklahoma. They aren’t going away, and neither are their stories. The Dignity Act, if passed, will be a win for these mothers, but it can only function effectively if we dramatically overhaul the scale and manner of oversight in prisons where pregnant populations are housed. Is this feasible? Maybe. But even then, we will, in many ways, be back to square one, critiquing the shortcomings of a system without acknowledging the nature of such issues: sewn into the fabric of the prison itself. Imagining and building alternatives to incarceration is a first step towards realizing a justice which is tangible and sustainable, one which hears the pains of pregnant mothers as legitimate, one which fights for a future that is restorative, rather than punitive.

NOTE: the description of a pregnant mother’s journey at MBCC is a fictional compilation of factual experiences, each unique, drawn from reports made to Rewire in their ongoing effort to document the treatment of women behind bars in Oklahoma, among other states, as well as the story of Aleia Holt as reported in NewsOK.

Featured Image Source: Alyssa Plese, BPR Design Team

Be First to Comment