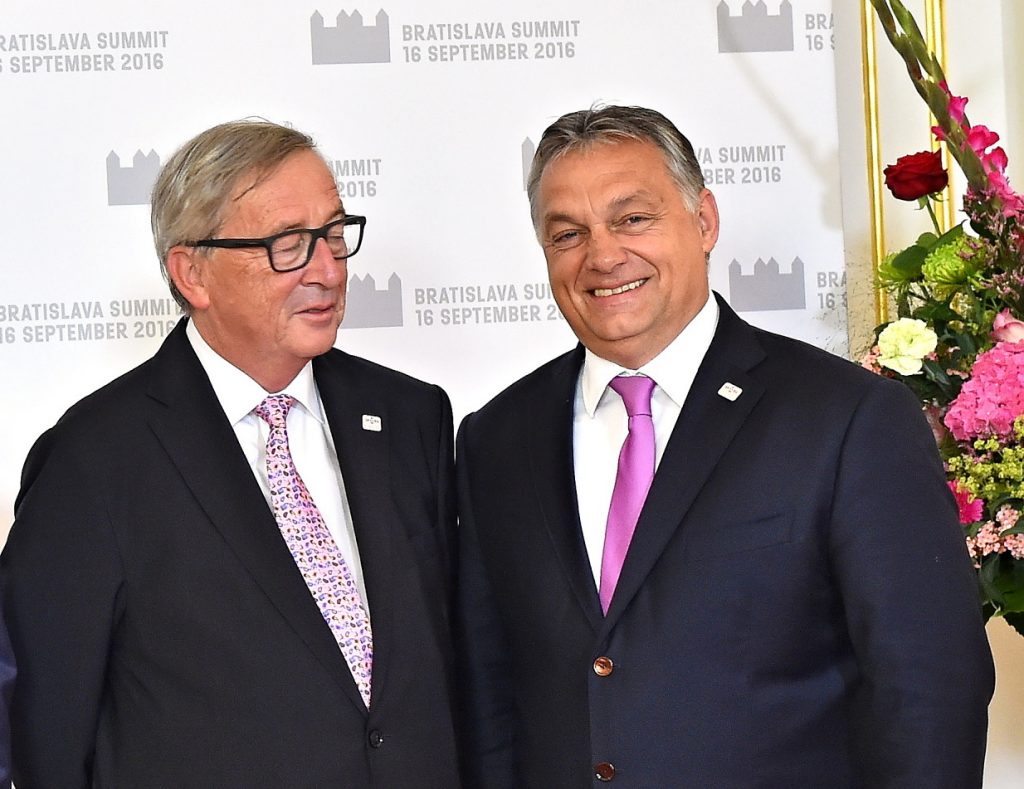

With a friendly slap in the face and shake of the hand, the president of the European Commission addressed Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as “dictator” during his visit to Latvia in 2015.

This name-calling was most likely in response to Orban’s recent appeals for an illiberal democracy, professing his plan to separate Hungary from “Western European dogmas.” Since then, Orban has taken major steps to follow-through on this promise, showing that the label of “dictator” suited him well.

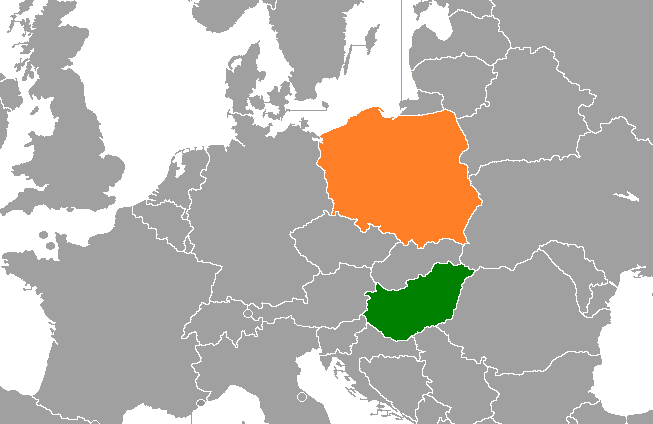

Recently, Orban and his ideological companions, specifically Poland’s former prime minister Jaroslaw Kaczynski, have moved further away from their democratic beginnings under the European Union. They argue that the EU needs to redefine its values on issues of immigration, Europe’s Christian roots, and national sovereignty.

BLUEPRINT FOR DEMOCRACY

Ironically, Poland had been the model for guiding Hungary toward democracy after the fall of the Soviet Union. Now, Hungary is pulling Poland away from the same values it had promoted in the 1980s. In 1989, Poland made the transition to democracy and provided a blueprint for Hungary and other Eastern European nations looking to throw off communism and align with the EU.

The Polish transition acted as a model for success, inspiring the opposition in Hungary to take action against a powerful and determined communist party. Roundtable talks began between Hungarian opposition and the authoritarian government, pushing the country towards democracy. The democratic movement found success and began to seriously challenge the communist government. This progress was unanticipated, and the weakened communist presidency had no option but to accept democratic elections.

CURRENT STATUS: ILLIBERALIZING

The communist party no longer exists in Hungary, having transformed into the Hungarian Socialist Party in 1989. However, since Viktor Orbán became prime minister, the nation has taken an authoritarian turn. His intensifying rhetoric against Western democracy and systematic dismantling of democratic institutions indicate movement towards an illiberal government.

Orbán has been reshaping the constitution to give less power to the people and more to the government. Currently, his FIDESZ party controls large parts of the judiciary, media, and banks. In the 2017 Freedom House report, Hungary was given the lowest “democratic score” (3.54 out of 7) in the Central European region.

With the support of Hungary, Poland followed suit. Former PM Kaczynski neutered the constitutional court, took over state media, defunded opposition NGOs, and appointed government-selected individuals to run civil society organizations.

Both countries are ignoring international criticism and protests. It’s as if Hungary is the new bad boy of Europe and its old friend Poland has along for the ride.

DOUBLE-TROUBLE IN THE EU

Orbán has always been outspoken in his critique of “Western-style” pluralism and immigration. At the start of the migration crisis in 2015, Orban became notorious for his brutality against refugees. He referred to them as “poison.” He built his own version of Trump’s wall on Hungary’s southern borders, using razor-wire fences to keep refugees out.

As the “defender” of the Hungarian nation, Orban laces ethno-nationalist rhetoric into every speech. He sees the Treaty of Trianon, signed after World War 1, as a historical injustice because Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory. His extreme ethnic pride results in consistent conflict with the EU over anything he interprets as an attack on the identity or sovereignty of Hungary.

In particular, Orban fought against the EU’s proposal of a quota system to deal with the migration crisis. He went so far as to take his case to the European Court of Justice. Also, when the EU threatened to sanction Poland for taking Hungary-sized steps towards an authoritarian government, Orban dismissed the proposal as pointless.

“It’s not even worth starting the process against Poland as there’s no chance to carry it through,” Orban said in an interview with state-run Kossuth radio. “Hungary will be there and form a roadblock they can’t get around.”

Orban and Poland’s current PM, Mateusz Morawiecki, are maintaining the long-standing good relations between their nations. The two countries gain evident power in their support for each other. It’s difficult for the EU to get a unanimous vote if Hungary or Poland consistently vetoes. The rebels of the EU have each other’s backs, for better or for worse.

WAS PLATO RIGHT?

There are various plausible explanations for the deterioration of democracy in Poland and Hungary.

One theory (Links to Paywall) parallels with Plato’s analysis of Democracy: these nations are wrongfully assuming that the will of a parliamentary majority is prioritized above all else. Through the implementation of this misconstrued ideal, officials are able to do as they please under the guise of large popular mandates. Unfortunately, in the complex transition to democracy, fledgling countries mistakenly forget a necessary part of successful democracy. For a democracy to be sustained, they need to establish a sort of Magna Carta, a framework of constitutional values that constrains the power of individuals in office.

Another theory (Links to Paywall) points to the roots of Poland and Hungary’s democracies. The two nations had only transitioned to democracy because of mounting pressure to join the EU. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the costs of being left out of the European Union were too high for the conflict-ridden nations to endure. As a result, they buckled under pressure and took on the new form of government mandated by the EU.

However, this response did not instantaneously lead to the adoption of the norms of liberal democratic institutions. The EU demanded institutional reform but failed to promote political equality, individual liberty, and the development of civil society. Now, the consequences of a shallow acceptance of democracy are evident, as these hollowed-out nations have been left vulnerable to illiberal predation.

“Europe seems like an old woman who is shaking her head in shock after reading the threatening news in the papers,” Orbán said in an interview with Bild, “But at the same time she forgets to close the door of her house.”

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Be First to Comment