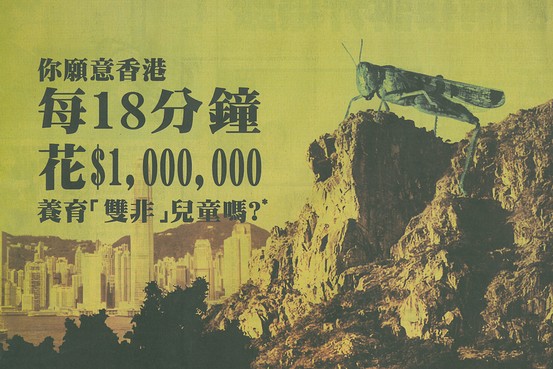

A giant locust sits perched upon a mountain, the Hong Kong cityscape in the distance. Next to it, bold black lettering asks, “Are you willing to let Hong Kong spend a million Hong Kong dollars every eighteen minutes on bringing up anchor babies?” Spanning a full page, this provocative advert ran in the popular Chinese-language magazine Apple Daily in 2012.

Tensions between Hong Kong citizens and “Mainlanders” were at an all-time high in 2012. As Hong Kong had a reputation for providing better access to commercial goods and services, mainland citizens often sought to make use of relaxed border controls to take advantage. This lead to a shortage of resources. The result was increasing animosity between locals and mainlanders, with locals calling mainlanders “locusts”; descending in swarms and ‘stealing’ much-needed resources from the local population.

Although this specific issue plaguing Hong Kong-Mainland relations has died down since 2012, the animosity hasn’t. “Locust” remains a slur directed at Mainland Chinese citizens in countless other protests. The rise of localism has only become more prominent with the formation of radical parties. And whilst much of this is directed towards resistance against the Hong Kong/ PRC government, a worrying amount of this animosity is directed specifically towards mainlanders themselves. This is misdirected anger, which not only damages relations between two groups that can work in solidarity but also results in xenophobia contrary to the notions of localism and counterproductive for future development.

In order to understand how this misdirection of anger has occurred, it’s important to first understand the context with which it has arisen. What exactly is localism, how has it come to be a prominent part of the Hong Kong political scene?

Localism, loosely defined, refers to a political ideology that is focused around the “preservation of Hong Kong’s identity and autonomy” (Law Wing-sang). With roots in cultural preservation, the term was first coined in 2005 protests to protect Hong Kong’s historic piers. Currently, Hong Kong’s parties and movements such as Demosisto and People Power, along with news organizations like the Passion Times, have emerged as explicitly localist. At best, localism refers to an emphasis on dealing with problems specific to Hong Kong, using diplomacy and mediation between Hong Kong and China. At worst, it comes with xenophobic tendencies towards immigrants, especially those of Chinese Mainland immigrants.

The localist movement is a product of complex factors, but can most clearly be tied in with a disenchantment with the Hong Kong government – particularly the pan-democratic wing. 2003 marked a breaking point for pan-democrats with the proposal of an ‘anti-subversion’ law by the HK government, which was dropped following a 500,000 person strong rally. Despite success in pushing back against this law, pan-democratic politicians were widely criticised in their failure to respond adequately, sparking the seeds for a more polarised split in the democratic wing of Hong Kong’s political state.

Since then, increasing interventions have been made by the HKSAR and PRC government to stamp out acts of resistance. At the same time, pan-democratic supporters have become increasingly disappointed with the pan-democrats lack of response and shifted to “radical resistance”. Groups like People’s Power have emerged with the ideology that more radical strategies should be used to challenge “Hong Kong communists ruling Hong Kong” and to defend against PRC government control over Hong Kong. This path has incrementally changed the political culture of Hong Kong, leading us to the rise of localism today.

Localists first gained prominent notice after the 2014 Occupy Central movement. Though unsuccessful in its demands for universal suffrage, it has since sparked a huge influx in the creation and growth of localist political parties. These too, have been divisive – transgressing the traditional left-right divide. Yet they have one thing in common: they are dominated by young people. Those of the “post-handover” generation, who have grown up without the colonial influence of the United Kingdom, tend to be most involved. For instance, the 2016 legislative council elections saw newcomers Nathan Law (23) and Yau Wai-ching elected (25).What might explain is the fact that the young adults of the “post-handover” generation are faced with inequality, unemployment, and rising house costs more severe than any prior generation.

This anger has manifested particularly in localist action and attitudes. Consider Youngspiration’s protest in 2015 against Siu Yau-wai, a twelve-year-old boy who had spent nine years in Hong Kong, which called for his deportation due to his status as an undocumented immigrant. At the same time, a survey conducted by HKU found that only 40% of citizens trusted the CPR. Compare this with results from 2008, where positive approval for the government was 53.1%. Though seemingly unrelated, one reason for increasing xenophobia can be tied to growing animosity towards the CPR government – highlighting a problem in the conflation between citizens from CPR and the CPR government.

It’s important to note that localism isn’t inherently xenophobic. Rather, its essential quality lies in an attempt at the redefinition of Hong Kong’s political identity – with some groups looking to reform and others looking for a total overhaul of the system. Yet within localist rhetoric, xenophobic attitudes towards Mainlanders persist. In her paper “Locusts” and and Localism: The Rise of Localism in Hong Kong, Hazel Wan-Hei Leung suggests that that “economic competition for resources” perpetuates anti-mainland sentiment “through Hong Kong government decisions which are perceived to have a hand in eroding Hong Kong’s identity and way of life, as well as the increased presence of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong and their tangible influence in the city’s allocation of resources”. What begins as dissatisfaction towards political institutions, coupled with a growing anxiety towards Hong Kong identity, becomes personalized and directed anger towards Mainlanders in Hong Kong.

In an interview with Berfrois, Joshua Wong claims it is “important to reflect on why right-wing groups like Civic Passion have had such an influence…they have contributed, in their own way, to the culture of the protest movement. They understand how to transform boring political issues into something subcultural”. While he’s right in terms of reflecting on their degrees of influence, it’s equally important to consider the ramifications of this xenophobic, anti-mainlander sentiment and the way in which it conflicts with “localist” ideology at its core.

From the point of view of ideology, if localism is inherently concerned with the notion of Hong Kong political identity, one needs to consider what exactly Hong Kong identity is. Hong Kong is a city formed of immigrants.Consider the waves of illegal immigrants between the 50s and 70s, with some suggesting that during that period approximately 2 million people illegally immigrated to Hong Kong from Mainland China. It’s undeniable that almost all people living there today are related to illegal immigrants. The immigrant identity is crucial to our understanding of what it is to be a Hong Konger, and so to perpetuate any sort of anti-immigrant view would be directly counter to that.

In choosing to direct animosity and hatred towards Mainland Chinese immigrants and tourists, we see that there is a misdirection of anger and energy to the wrong targets. We’ve thus far identified that many of the problems that have emerged leading to tensions between Hong Kong citizens and Mainland Chinese citizens can, in fact, be pointed out to problems in two places: the HKSAR government or the PRC government. The conflation between PRC immigrants to Hong Kong and the PRC government assumes a guilt by association. This is unfair, unproductive, and ultimately serves to hinder cohesion that could lead to actual change in Hong Kong.

As a Hong Konger, I’m concerned about where this leads. Already, discrimination towards immigrants – particularly those from Mainland China – is rampant. Such discrimination is problematic in the imagining of a future for Hong Kong if it is to continue to sustain and develop itself in the way that many localists hope it will do. Hong Kong localism, no matter the appeal of the rhetoric, must shift away from anti-mainlander – no, anti-outsider standpoint. This is the only way we can conceive of a truly democratic system for all Hong Kong citizens, both present and future.

Featured Image Source: https://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2012/02/01/about-that-hong-kong-locust-ad/

2 Comments