At 2:19 pm on February 14th, I was basking under the pleasant skies on memorial glade, a common pastime of any Berkeley student on a sunny day. At 2:19 pm on February 14th, Nikolas Cruz had entered Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School with the intention of committing murder. The current discourse surrounding the Parkland high school mass shooting is engulfed by the status of gun rights in the US, and rightly so. But, often missed and hidden in the crevice of this gun rights debate is the question of the death penalty. The prosecution, the party conducting legal proceedings against Cruz, is currently grappling with the dilemma of whether to charge Cruz with capital punishment. It is not the matter of whether he will get the death penalty or not, but rather why the option of death penalty is available. Aside from its evident uselessness, the state has a moral obligation to protect the right of life in all individuals, even those who have committed unspeakable crimes such as this.

The Right to Life

While the US Declaration of Independence states that we are all granted the “inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”, it is evident that there are limitations. The fifth amendment Due Process clause states that “the State shall not deprive an individual of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” It seems that these rights aren’t absolute. Each individual in a society surrenders some freedom for the collective good. For instance, there will be legal retribution if I decide to set houses on fire for the sake of free speech- an infringement on my liberty. Yet, there is something unsettling in the actual infringement on another person’s right to life. Life is defined in the narrowest sense as the ability to breath, live, experience, and most simply exist. Perhaps the distinction between life and liberty lies in that liberty has been socially constructed. The right to speech, or the right to privacy, were all created and defined by people. But life, by definition, is inherent and natural to the person. A person, as a living being, would not be a person if not for life. As argued by Peter Riga in the University of Pudget Sound Law Review, “life does not belong to society and it is for that very reason that the state cannot, in principle, take life.” Hence, the actual existence of a person is independent of the dimensions of society, and would exist even if society was absent.

Our laws can be considered an aggregate of each person’s individual liberty that is given to society for the collective good. However, enlightenment philosopher Cesar Beccaria argues that we do not give up the right to life as part of this “social contract”. No person hands to the government, or fellow people, the ability to capture life on their terms. In his book “On Crimes and Punishment”, he states that the right of people “to cut the throats of fellow creatures” is not the right on which “sovereignty and laws are founded”. The reason as to why a hypothetical “contract” between the government and people was formed was to maintain social order. By preserving social order, the government would be able to preserve the basic rights of individuals, one being life. Why would people have assembled, and chosen to give up a few liberties, and chosen to create a government, if not for the greater good of securing certain essential liberties and rights? When there are other manners in restraining an individual and preserving society, such as prison, it does not make sense for the government to take someone’s life. These certain rights and liberties that deserve the greatest of protections, as defined by a society, are contingent upon life. Thus, all life, regardless of what liberties society designates as being most important, deserves at least the same amount of protection as well.

Even in a constitutional democracy that is ostensibly run by the “consent of the governed”, our life should not be a leveraging tool which the government can use to maintain control. For the government to have the ability to take the life of its people is the greatest form of betrayal.

So, why do we still have the Death Penalty?

President Trump, on November 2, 2017, tweeted that Sayfullo Saipov, who drove a truck into crowds of people in New York City, “SHOULD GET THE DEATH PENALTY.” It is difficult to argue against capital punishment, especially when it regards serial rapists, murderers, terrorists, and child abusers. This fight for “justice” is enticing, but when “justice” involves the state murdering the murderer, it is also a bit hypocritical. Fundamentally, capital punishment is flawed and immoral. Since 1977, 140 people have been released from death row due to wrongful conviction while 1200 people have been executed. Amnesty International provides further information on how the death penalty is racially based, how it does not deter crime and how it does not serve justice.

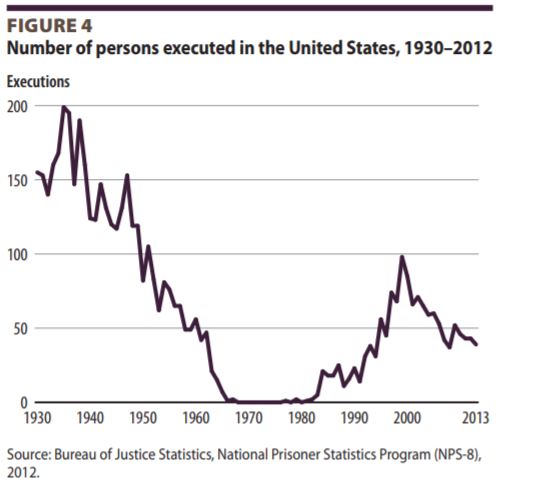

Most people realize the inefficiency of the death penalty. The United Nations condemns the practice, and the US is the only western nation to continue its implementation. In fact, there was a gradual decrease in the usage of the death penalty till the 1980s, and from the 1970’s-1980’s there were nearly no executions.

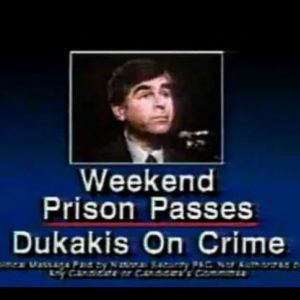

Then, why is the institution of capital punishment still so entrenched in our society? The answer is almost too simple: politics. In 1971, Nixon declared the “War on Drugs.” This completely altered the perception of criminals. The rhetoric surrounding those who had broken the law portrayed them to be inherently evil and incapable of change. Along with the call to maintain “law and order” came the resurgence of capital punishment. Politicians capitalized on people’s fears of crime, and the death penalty was an easy way to appear strong. The political nature of the death penalty is best illustrated with George HW Bush’s attack ad on Dukakis in the election of 1998. Dukakis, the Democratic candidate, opposed the death penalty. This ad, which criticized his position on capital punishment, is often regarded as the reason Dukakis lost.

Conclusion

Thomas Jefferson said that “laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.” There might have been a time when executions were the most successful method of curbing violence and unlawfulness, or when it was unanimously considered to be necessary. However, in the modern day, we have developed other institutions, methods, and principles of governance that do a much better job of regulating society and don’t necessitate the killing of individuals. If the government is to maintain its integrity, and if the United States is to champion human rights and democracy around the world, we must begin by demolishing one of our most unjust institution: the death penalty.

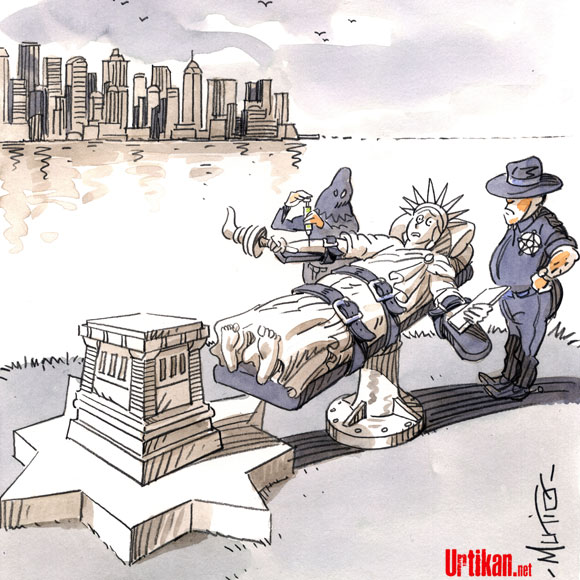

Featured Image Source: Urtikan.net

Be First to Comment