CRIMINAL

You’re a drug dealer who’s just been busted for possession with intent to distribute. You started dealing in college to help pay for tuition and promised you would stop after graduation. Beads of sweat shoot down your face as you realize the evidence is stacked against you and could do up to ten years. The officer, frustrated you won’t answer his questions, gives you a piece of advice as he closes the backseat door to the cruiser. “You better have a damn good lawyer.” You know your sentence is not going to punish you for being a drug dealer, but rather for not being able to afford a top notch lawyer.

Does the amount of money spent on legal representation correlate to the quality of representation received? Do you have a better chance of winning a case with a private attorney instead of a public defender? Has the the American justice system failed to provide an equitable platform and instead become an institutionally flawed structure granting an unfair advantage to affluent Americans?

In theory, legal service runs on a scale where the most legal expertise is rewarded with the most pay. The average salary for lawyers who graduated from top law schools is significantly higher than lawyers who graduated from less prestigious law schools. Private sector lawyers in the United States earned an average salary of $118,160 in 2016 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and graduates of the top earning nineteen law schools earned a median income of $160,000. Law schools with the highest median salaries flaunt these statistics as an advertisement for how successful their school is. The American Bar Association found in 2012, the average public law school tuition was $23,214 and the average private school tuition was $40,634. With the increasing costs of law school, graduates are enticed now more than ever to seek private practice as a means to pay off student debt.

In practice, however, legal expertise cannot be measured by salary nor what school you attend. The median salary of graduates from the same law schools who went into the public sector is closer to $55,000. It is too big an assumption to assume graduates of the same law school have the same amount of legal expertise, simply because of all the variables associated with finding a job. It can be said, however, that graduates of the same law school may have comparable expertise because the education they receive is the same. Is it really the case that private attorneys who charge more are more adept at winning cases?

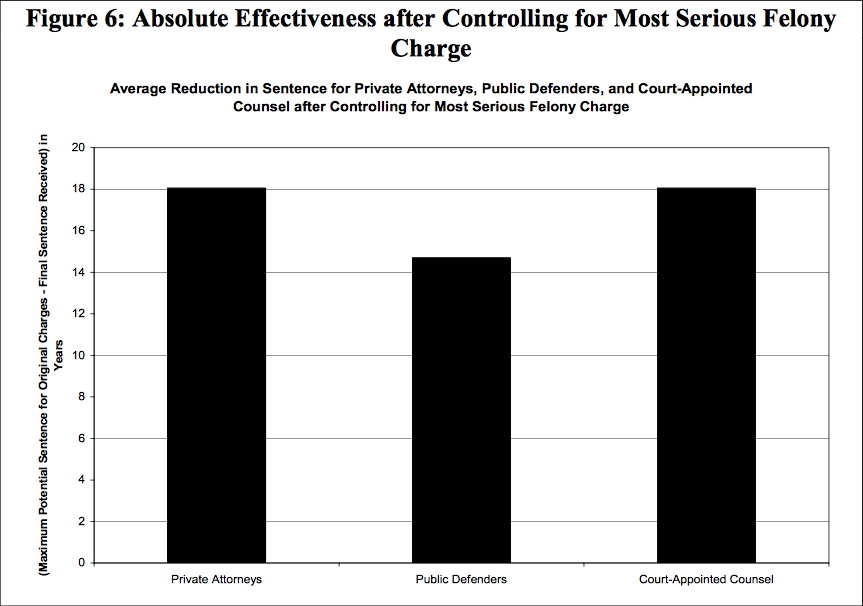

In a paper titled “How Much Difference Does the Lawyer Make? The Effect of Defense Counsel on Murder Case Outcomes,” researchers at the Rand Corporation found “public defenders in Philadelphia reduce their clients’ murder conviction rate by 19% and lower the probability that their clients receive a life sentence by 62%. Public defenders reduce overall expected time served in prison by 24%.” However, the effectiveness of public defenders and private counsel at reducing sentences is far from conclusive, especially at the federal level. A paper published in the Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law found that “An average public defender client was sentenced to almost five more years of imprisonment than the average private lawyer client.” The study argues marginally indigent defenders are more likely to use a public defender if they are guilty of minor charges, like a misdemeanor. Conversely, they are more likely to hire a private counsel if they claim innocence in the face of more serious charges like murder or drug trafficking. This suggests public defenders may have less defensible cases, taking guilty defendants willing to pay the price. But even when accounting for case severity, the Ohio researchers found public defenders were still less effective than private attorneys: “The average public defender client was sentenced to almost three more years of incarceration than the average private lawyer client facing an equally serious charge.”

Why would public defenders be less effective than private counsel? From an economic perspective, one can argue public defenders lack the incentive of being paid by a wealthy client, in addition to a sense of personal obligation to said client. A report published by the American Bar Association points to public defenders’ caseload as a possible reason. “Caseloads are so excessive that in many jurisdictions defense counsel are unable to perform even core functions, such as conducting an adequate factual investigation into guilt or innocence.” The Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics reports 15 out of 22 statewide public defense systems have caseloads exceeding the national standard. “Misdemeanors and ordinance violations accounted for the largest share (56%) of cases received by county-based public defender offices.” Using the analysis from the Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, public defenders fighting misdemeanor charges are more likely to be ineffective as their private counterparts because clients would more often choose to be represented by a public defender if they are guilty and their offense is not severe. Researchers from the Journal conclude “But our results suggest that even if we posit equal skill in case evaluation, public defenders will still be less effective—not because they are bad or overworked lawyers, but simply because they attract less winnable cases.”

In summary, public defenders are not less effective than private attorneys because of a lack of skill, rather by the very nature of being public defenders. The large caseload and the propensity for guilty clients to use public defenders leaves them overworked and with deceiving statistics that deem them worse lawyers. However, public defenders cannot select which cases they take in the way a private attorney can, nor do they have any control over the type of clients attracted to them. Public defenders are always subject to fluctuations in government funding, less pay than their private counterparts, and less personal accountability to their clients. The implications of this means an impoverished person represented by a public defender is more likely to be convicted/receive a longer sentence by no fault of their own.

CIVIL

Civil cases, unlike criminal cases, can be more heavily influenced by the amount paid for legal representation. Unlike criminal cases where a defendant is provided an attorney under Article Six of the Constitution, both parties pay for their own representation in civil court cases. Thus, both parties can splurge as much as they want to try and get the best lawyer.

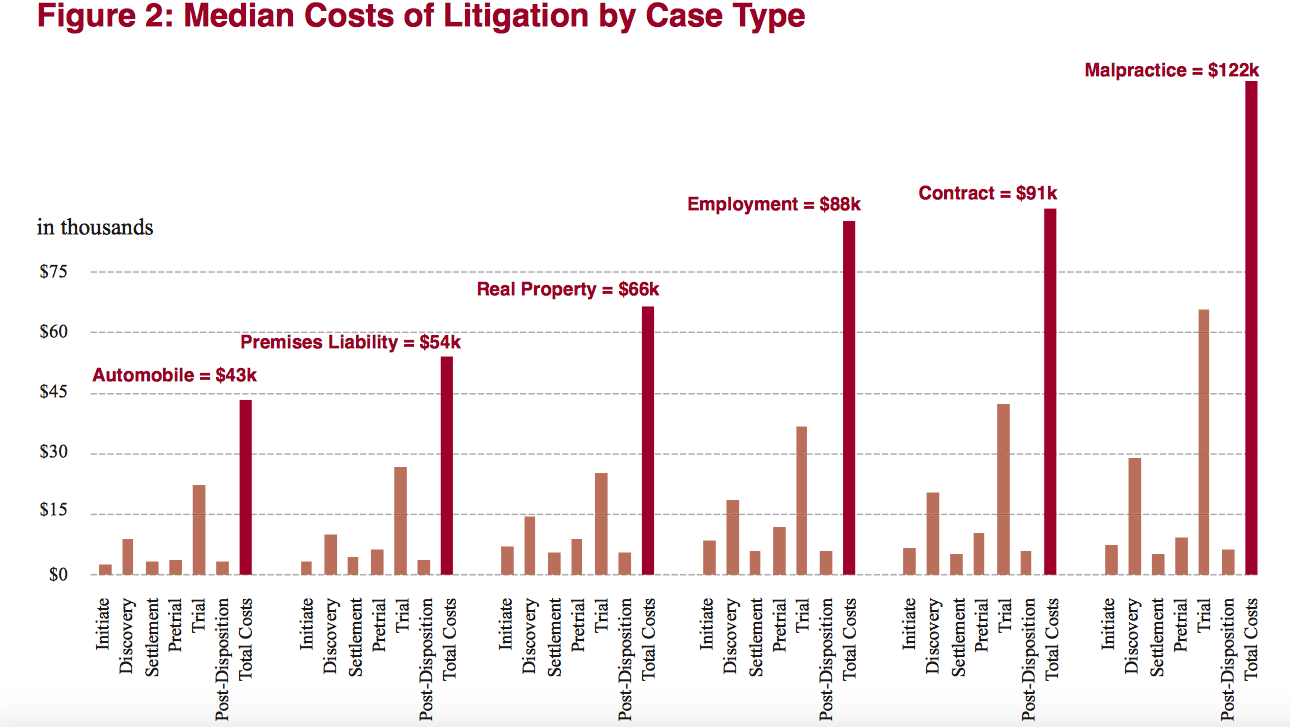

It is not uncommon for civil law attorneys to charge $250 an hour. The plaintiff is also liable to pay for all the court fees associated with the case, including filing fees, daily depositions, and fees involved with expert witnesses. A group of lawyers from the American Board of Trial Advocates (ABOTA) reported a typical automobile tort (private wrong against another) case, a common civil case filed, requires a median of 196 hours, and billable rates ranged from $150 to $375 per hour. The total costs for attorney and expert witness fees averaged to $43,238, a steep price to pay for a typical civil case. Considering the average American household income is $59,039 according to the Census Bureau, it is unlikely many people have 40,000 dollars lying around to spend on litigating a civil case. Sadly, automobile tort cases are among the less expensive variants of civil cases. The National Center for State Courts has provided median costs of litigation for other case types.

The average American simply cannot afford to go to a civil case trial. This subjects innocent people to injustices by a powerful defendant. Andrew Tesoro is an architect who claims Donald Trump cheated him out of thousands of dollars after constructing a clubhouse at one of Trump’s golf clubs. Tesoro claims Trump refused to pay him for the amount that was agreed upon, being paid $25,000 instead of $140,000. After consulting with a lawyer, Tesoro was advised to simply take what he could and not fight the incident in court because the cost of fighting the Trump Organization would be too expensive.

Wage theft can happen to anybody, not just high-end architects. Heriberto Zamora was an employee at Urasawa, an upscale sushi restaurant in Beverly Hills. Working nearly sixty hours a week and not getting paid overtime, Zamora was fired after asking if he could go home early one day. Wage theft refers to the act of not paying employees for their work, and can manifest itself as not paying for overtime, stealing tips, etc. Victims of wage theft are often minimum wage workers like Zamora who definitely cannot afford civil court. According to the UCLA Labor Center, “eighty-three percent of workers who hold a court-ordered claim to receive their unpaid wages never see a dime.” So even when the process goes smoothly and workers report crime as it should be, there is no justice in terms of redress for stolen wages. 60 percent of employers have “abandoned, transferred or sold their business without paying their employees’ wages, despite a judgement ordering them to pay.” Ineffective civil courts incentivize businesses to use exploitative practices in order to avoid paying compensation for wage theft. Not only is there underreporting of wage theft, but even when victims go through the legal process, they are often not rewarded with any justice.

The cost of civil courts has incentivized people to settle their problems outside of court. People are encouraged to settle their divorce out of court or take settlements from wrong-doing businesses. This is generally not a problem between two consenting parties, but amicable relations are prevented when one party threatens to sue. Civil court plaintiffs like Zamora often hold legitimate grounds to sue, medical malpractice or stolen wages for example. The sheer costs of litigation for cases like these deters people from actually pursuing the defendant in court, effectively preventing victims from receiving justice. The ineffectiveness of the courts in serving justice enables innocent people to be exploited by powerful actors including companies, affluent people, etc. Of course, for the person who can afford the costs associated with civil litigation, justice is in no way deterred. A recent survey reported by Forbes found 63% of Americans do not have enough savings to afford a $500 emergency. For the average American, the only thing served in civil court is a false promise of blind justice.

Featured Image Source: Avnphotolab Via Getty Images

Be First to Comment