I recently watched the new Jackie Chan movie called, The Foreigner, which is basically a Chinese Taken (highly recommended, by the way). But what stood out to me was the title. The only reason this title is even pertinent to the movie is the character that Chan plays, an immigrant in the UK who fights the IRA in order to avenge his daughter’s death at the hands of an IRA bombing. If anything, it follows an ingrained myth of Asian Americans being the perpetual foreigner, which isolates and divides Asian Americans from the rest of civil society and perpetuates harmful stereotypes. This changes the political efficacy of Asian Americans, as the myth believes that the political machine is not one that includes Asian Americans, especially when the sociopolitical culture reifies these forms of racism. Specifically, there are five myths of Asian Americans: the model minority, the yellow peril, the docile worker, the perpetual foreigner and the asexualized body. However, concerning the focus on the divide between Asian Americans and political participation, there are specifically three myths that primarily contribute to this divide: the model minority, the yellow peril, and the perpetual foreigner. While the other myths contribute to a larger holistic picture of apathetic voters in the Asian American community, these three myths construct the prime motivation of voter apathy. Note that this is not a holistic examination of Asian American voter apathy, but a perspective rooted in theory and racial divides.

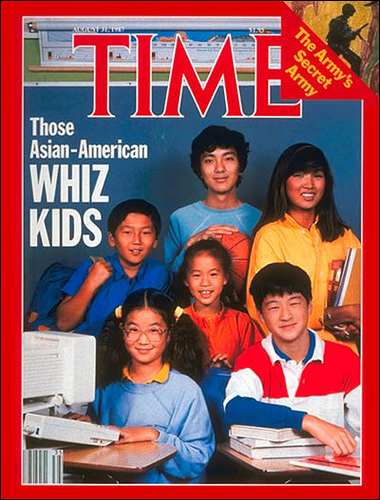

The Model Minority

The thesis of the myth of the model minority has much to do with the history of Asian Americans and their economic status in the United States. The simple idea is that Asian Americans have long been a minority group in the United States, but unlike other minority groups, Asian Americans have achieved a middle-class status, or so we are led to believe. This primary assumption leads to a comparative evaluation of other minority groups that assume that the United States has become a society in which any minority can succeed, they just need to be like the Asians. Not only is this a false equivalency that conflates and homogenizes the experiences of different racial minorities in the United States, but it also ignores the insular problem that the model minority thesis hides, which is that the economic success of Asian Americans cannot be the sole determining factor of bridging the racial gap, and also overlooks the economic struggles that Asian Americans face.

Specifically, the comparative statement that pits other minority groups to Asian Americans by showing that if Asian Americans could succeed, then other racial groups should be able to as well, ends up leaving out the large structural and systemic barriers that exist. The threat construction of Asian Americans, for instance, is radically different from the criminalization of blackness where, “[t]he brute image of Black men became significant moving into the early 20th century, when fear was reinforced with depictions of Black men as harmful” that ties into the brutal era of slavery and Jim Crow where black men were seen as criminals, savages, and thugs. Such large disparities come at the cost of intergenerational wealth accumulation, where we need to highlight “the importance of intergenerational transfers of wealth and past and present barriers preventing black wealth accumulation” and not just assume that just because the Asians did it, other groups should be able to as well.

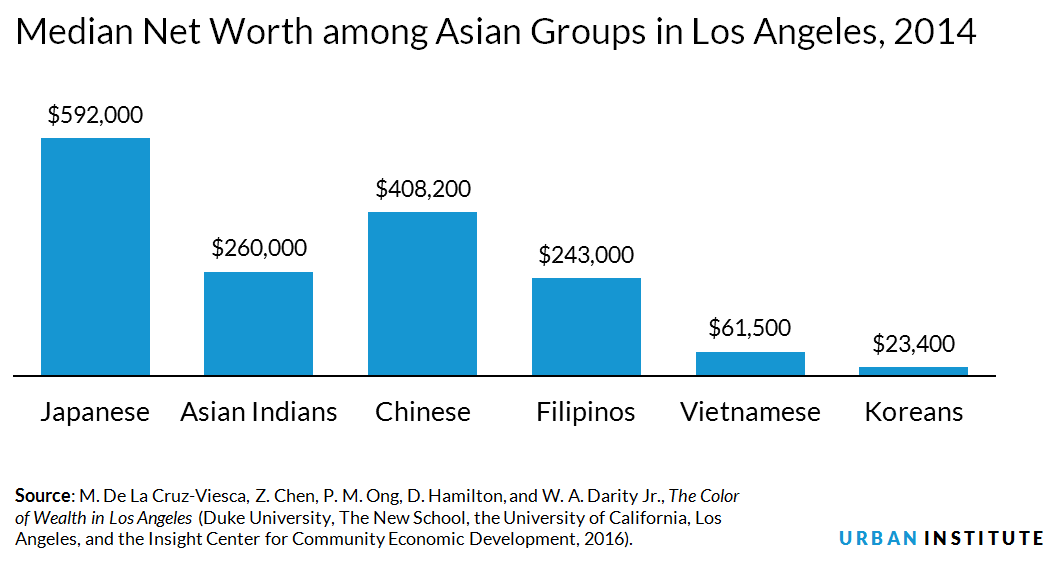

Not only that, but the data surrounding Asian American wealth accumulation paints a different picture of the model minority status. First, the monolithic understanding that Asian Americans as a group fare better as a whole is wrong (pictured below), and specific ethnicities within the Asian American diaspora show a diverse data set:

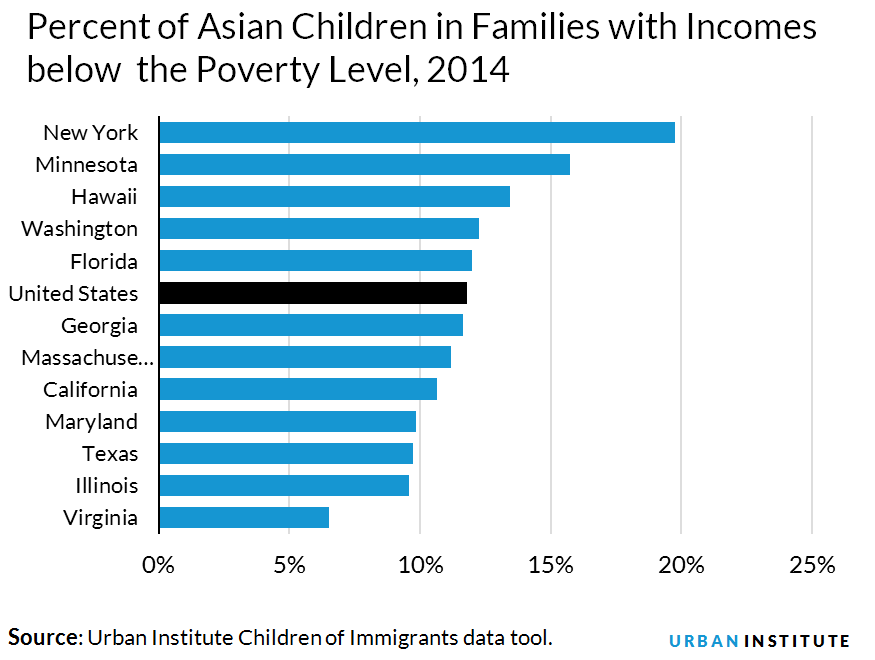

Not only that, but the perception of Asian American families below the poverty line is also wrong, where the variation by state shows that it is not as utopian as we would like to believe (pictured below):

The model minority myth is not just about the economic status of Asian Americans, but it also encompasses the general attitude that Asian Americans are well off, but the large divide also has to do with the lack of diversity in Congress. The recent 115th Congress, for example, has the highest amount of AAPI representatives but sits only at eighteen AAPI representatives, out of the 538 representatives in the House and the 100 senators in the Senate.

Why would the model minority myth impact Asian American voting? If the myth is internalized it would have Asian Americans believe that there are no real policy measures to fight for and that there is no construction of modernity that could benefit them further. The notion that other racial groups are struggling due to their own accord would also fracture the necessary coalitions that would lead to less support to social justice initiatives and demands, such as Black Lives Matter, while creating a cognitive dissonance towards the historical realities and violence that Asian Americans have had to endure in America.

The Yellow Peril and the Perpetual Foreigner

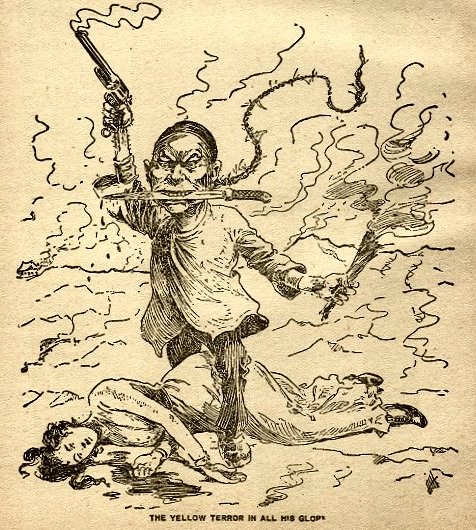

Long before the myth of the model minority, the primary racial anxiety of Asian Americans had much to do with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and its extension, the Geary Act, once the CEA had expired. The CEA had come around a time in the 1800s where thousands of Chinese laborers had completed the Transcontinental Railroad, and white Americans were now worried that their jobs would be lost given a number of laborers that were available and created a root of anti-Chinese, and by extension, anti-Asian sentiment that rang for decades to come. The construction of the yellow peril coincided with the attitudes that Asian Americans were just not real Americans, and that the categorical designations created by white Americans during this time, ended up having Asian Americans realize that we would never truly be American and that there is always some part of us that is perpetually foreign.

The CEA and the Geary Act severely limited Chinese and, when the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 came about, Japanese immigration as well. The policies themselves were not the only racist attitude to come about, as the push for these stricter immigration policies were also accompanied by racist propaganda (pictured above and below):

Many of these posters and attitudes stereotyped the Chinese as “degenerate heroin addicts whose presence encourage prostitution, gambling, and other immoral activities.” The poster above, particularly, shows that Chinese men were dangerous to white women and solidified a threat paradigm that has changed and evolved.

The modern yellow peril takes place in studies of international relations, specifically the realist school of thought, where people like Professor John Mearsheimer from the University of Chicago make statements in his work “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics,” such as “…China and the United States are destined to be adversaries as China’s power grows” and where he continues to recommend that the United States should deliberately seek to slow the economic growth of China, effectively stunting the opportunity and ability of nearly 1.4 billion people in the global community. By contrast, in Chengxin Pan’s work “Knowledge, Desire and Power in Global Politics: Western Representations of China’s Rise,” Pan, a senior lecturer in International Relations at Deakin University, states, “without acknowledging their own role in the production of the ‘China threat’, ‘China threat’ analysts thus play a key part in the spiral model of tit-for-tat Sino-US relations,” later stating that such attitudes are “commonplace in the China watching community, reflecting an intellectual blindness to the self-fulfilling nature of one of its time-honored paradigms.”

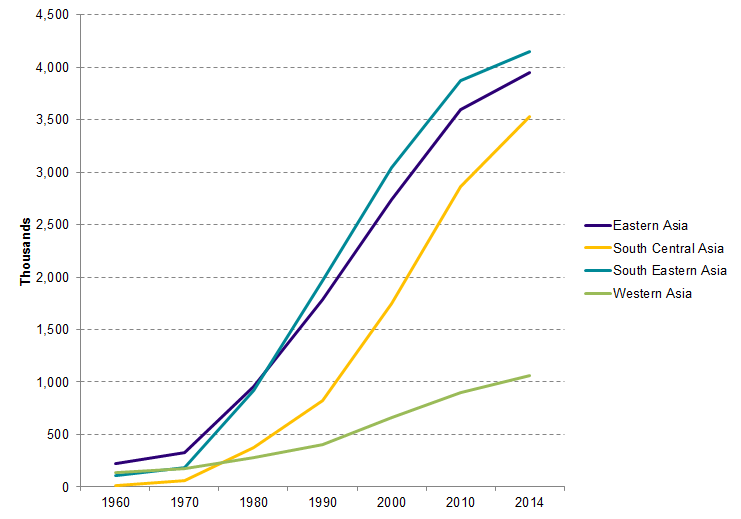

This type of political posturing creates an internal conflict for the large Asian American immigrant community, and by extension, first-generation Asian Americans as well, Especially since Asian American immigrants has been steadily increasing over the last couple of decades (pictured below):

This divide doesn’t just present in theory, and it even has infiltrated our domestic talks on the economy and politics. Take a look at this segment from “The O’Reilly Factor” where Jesse Watters ambles down to Chinatown and “gauges” political opinion on the 2016 election where he harasses elderly Asian people who don’t speak English and plays off racist Asian tropes. Even Trump’s rhetoric, based on the long-held belief that jobs are somehow being stolen by Chinese workers is no longer a reality. This divide sharply places Asian Americans in the political periphery as there is a constant antagonism between two notions of “home,” where the United States may not feel like such a safe haven, but the political and military conflicts in places like South Asia, for instance, are not exactly as welcoming. These sharp racial divides have been so internalized into the Asian American identity that traditions like voting are not commonplace, and they reflect on how political campaigns are run, where presidents do not seek to appeal to Asian American interests or voters. This apathy is based on racial tropes, not just in an insular sense of identity, but by how these myths end up being grafted onto the American political machine, where Asian American voters are, sadly, consistently invisible.

Featured Image Source: The Huffington Post

One Comment