“I am become death destroyer of worlds” said J. Robert Oppenheimer, quoting the Hindu scripture The Bhagavad Gita, as he watched the first nuclear weapon explode before his eyes. Since then, the US nuclear arsenal has changed dramatically to confront evolving adversaries, but our overreliance on land-based missiles may make Oppenheimer’s apocalyptic rhetoric a reality.

President Trump warned of the “fire and fury” that would befall North Korea if they did not stop testing increasingly threatening missiles on Aug. 8. The question, then, is what fire and fury was the president hinting at, and more importantly, if it lives up to his apocalyptic rhetoric. 400 of the currently deployed nuclear warheads are in Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, or ICBMs for short. The Air Force operates the ICBMs from silos in the continental United States. From failed security tests to outdated technology and the strategic hazards if they were ever actually used, it is a wonder that the United States still makes use of these land-based nuclear weapons. The reason for their continued use is at the core of American military strategy — politics.

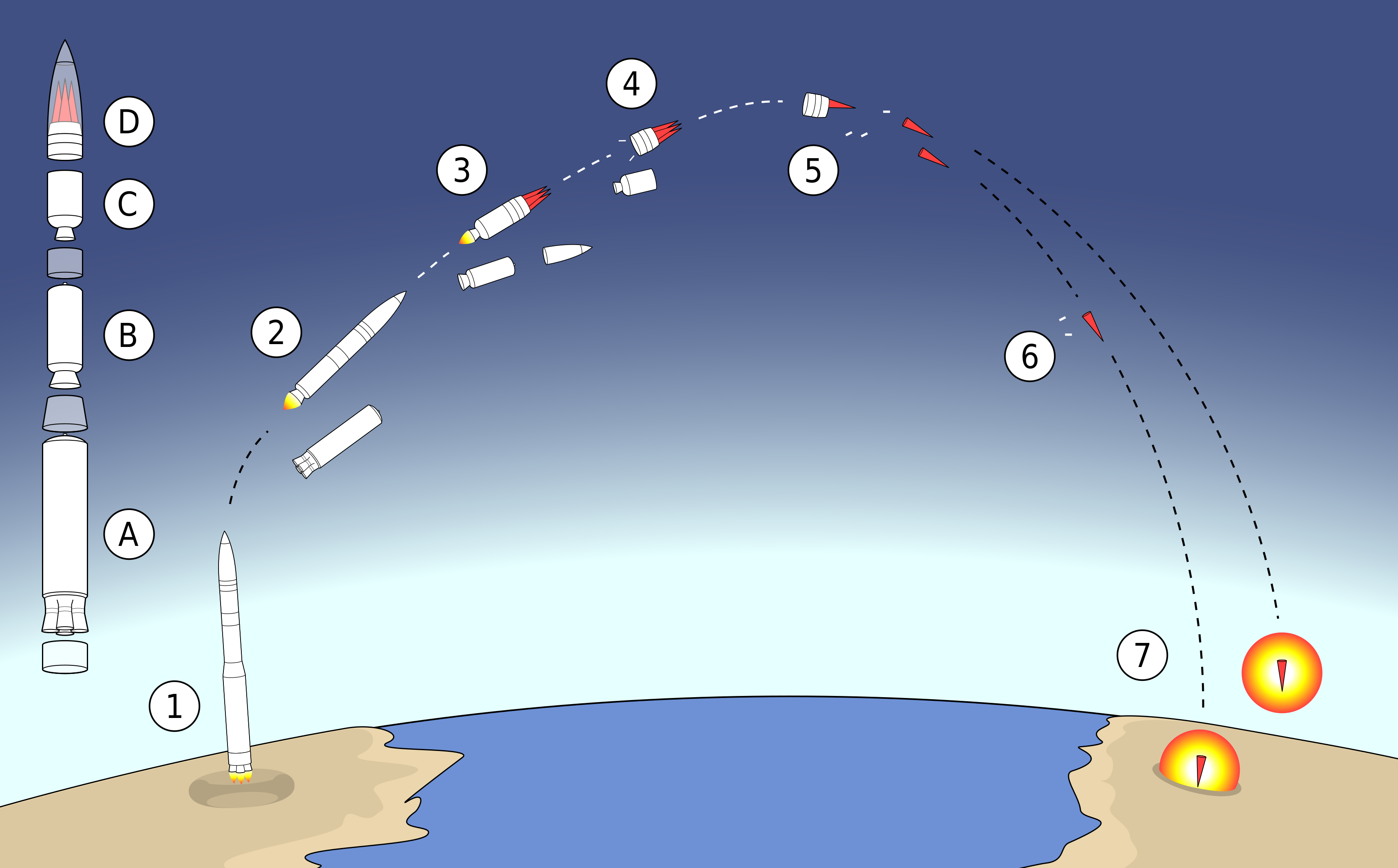

The most immense nuclear weapons, such as the Soviet Union’s “Tsar Bomba” tested in 1961, are capable of destroying structures over 12 miles away from the target and incinerating anything within two and a half miles in an inescapable fireball. Ballistic nuclear missiles are shot into space and use gravity to rapidly descend towards their worldwide targets. That high altitude trajectory, utilizing gravitational pull, is what makes them “ballistic.” North Korea’s ballistic missile, launched Sept. 15, reached an altitude of 480 miles and flew about 2,300 miles. The platforms used to launch nuclear missiles are diverse, each with their own complications. In the US, three main platforms comprise the “nuclear triad”: sea-based submarines, air-based strategic bomber planes, and land-based missile silos.

Nuclear Conflict

The primary objective of a nuclear missile system is its ability to deter and, in extreme cases, respond to international threats. That mission is where our silos fall flat. If nuclear deterrence fails, and countries are forced to engage in nuclear war, ICBMs must be launched quickly or they will be decimated, nuclear security expert and Princeton research scholar Bruce Blair said in an email interview. Land-based nuclear missile silos are not as secretive as submarines or planes because their locations are publicly known. The 400 “Minuteman III” intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, are housed at Air Force silos in Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, North Dakota, and Montana. Bombers also have to be launched quickly, but unlike ICBMs, they can be recalled after launch. “‘Use or lose’ forces like them put inordinate pressure on decision-makers,” Blair said, “and increase the risk of launch on false warning.”

Attacking North Korea with ICBMs is improbable, according to Blair, because silo-based missiles would have to fly over Russia and China to get to North Korea. Those flights would risk triggering a false-warning retaliatory launch. If a country detects an incoming ICBM, waiting until the missile is clearly aiming toward a particular target can be too late. Russia or China can’t afford to wait for the American ICBM to clearly be aiming toward North Korea before deciding what to do, because if it were to aim at them, they wouldn’t know until it was only a matter of minutes before they were struck. That’s why, for their own security, any country that detects an incoming ICBM has reason to strike back. As far as they would know, if they hesitate, they risk annihilation. The only rational choice for a country detecting an incoming nuclear missile is to prepare and strike back to disable the enemy’s nuclear launch systems. Those launch systems, if we use ICBMs, are in the heartland of continental United States. If the US uses ICBMs against North Korea, it would be an easy way to start global nuclear war.

Alternative Platforms

The submarines used for launching nuclear missiles are called “boomers” and have months-long patrols near potential targets around the world, making them far more secretive than an ICBM. Over 60% of their patrols are in the Pacific to deter threats from China and/or North Korea. Their exact locations are top-secret, almost as restricted as the nuclear launch codes themselves. The missiles they fire are “submarine-launched ballistic missiles,” or SLBMs for short. The United States operates 14 Ohio Class submarines, each carrying at least 20 Trident II ballistic-missiles. Each missile carries around five warheads, meaning that each of these hidden submarines silently patrols the globe carrying nearly 100 nuclear warheads in total.

Strategic bomber planes, commonly called bombers, each carry 16-20 non-ballistic nuclear bombs. The Air Force currently operates two types of nuclear-capable bombers, totaling 18 B-2s and 70 B-52Hs. Each can fly at altitudes of 50,000 feet and has a range well over 6,000 miles. The payload for their nuclear weapons range from a minimum of 10 kilotons, enough for a blast radius of almost a mile, up to a maximum of 1.2 megatons, enough for a four-and-a-half mile blast radius that could level a major city. Like our submarines, the location of a bomber in-flight can be highly secretive, but it can also be a show of force to countries deemed threats.

Silo Security

Nuclear missile silos are plagued with a history of poor security. Silo blast doors were left open in a particularly embarrassing 2013 incident. An airman left the blast door open to receive a food delivery, while the other crew member was on an authorized sleep break. However, Air Force officials said that “there are multiple layers of security above ground that would keep unauthorized personnel from gaining access to a launch control center.” In a separate training incident, an Air Force security team failed a drill simulating an attack on a nuclear missile silo. For that missile silo, an attack by violent non-state actors could end with the theft of active nuclear warheads in the domestic United States. The threat of violent actors forcibly infiltrating the United States, breaking into missile silos, and stealing nuclear weapons is not a fear many Americans have, but if domestic terrorism ever becomes more militarized, it is a serious concern. These weapons would not even require missile capabilities to reap catastrophic consequences, because they are just one long freeway drive away from their nearest targets. The security for our silos should be absolute, but recent failures have raised doubts about whether some of our most dangerous weapons are safe from catastrophe.

Comparably, “bombers have the highest chance of crashing, but their nuclear warheads are kept in storage igloos. Submarines have the best security because no one can get near them when deployed at sea,” according to Blair in an email interview. Regardless of the funding that specific protocols that nuclear silos may take to increase security, they will always be the least secure wing of the triad.

Missile Technology

Silos are also the least technologically proficient, which is critical considering that they are dealing with the most powerful weapons ever made. The newest of the silo’s missile systems are from the 1970’s, said Tufts University professor and national security expert Jeffrey Taliaferro in an email interview. Originally, silos were invented to allow troops to fuel liquid-based missiles underground without being exposed to enemy attack. Current nuclear weapons mostly use solid fuel, which does not require a lengthy fueling process. Additionally, silos are much further from their potential targets than a submarine or plane, increasing the potential time-to-target for a missile. Recent administrations have sought to upgrade ICBM technology, but submarines and planes already meet the accurate needs of a US missile system. Submarine-based ballistic missiles developed in the Cold War were already as accurate as their silo-based counterparts, according to political science professor and nuclear weapons expert Stephen Cimbala in his book Military Persuasion: Deterrence and Provocation in Crisis and War.

Politics

Secretary of Defense James Mattis previously supported eliminating the silo-based missile system. He changed his position after taking office, citing the need to maintain the perception that the US is still capable in nuclear weapons technology. He has not, however, isolated why ICBMs are uniquely critical.

ICBMs are protected in congress by the Senate ICBM caucus, said Blair. “A lot of money is spent on ICBM operations in these states and new money will begin to dribble down over the next few years as the replacement missile development and preparations are undertaken.” He cites the jobs that the bases provide as being critical for these senators. The 90th Missile Wing alone, located about three miles west of Cheyenne, Wyoming, has a total of almost 10,000 employees and family members that directly support its local infrastructure.

With sufficient alternatives in submarines or bombers, it is clear that there is no military justification for the continued use of silo-based nuclear missiles. Silo-based nuclear missiles have old technology, shoddy security, military danger, and superior alternatives. If the US focused on making its military as streamlined and effective as possible, it may not have any need for the potentially apocalypse-producing ICBMs.

Featured Image Source: Creative Commons. Author: 2nd Lt. William Collette.

Be First to Comment