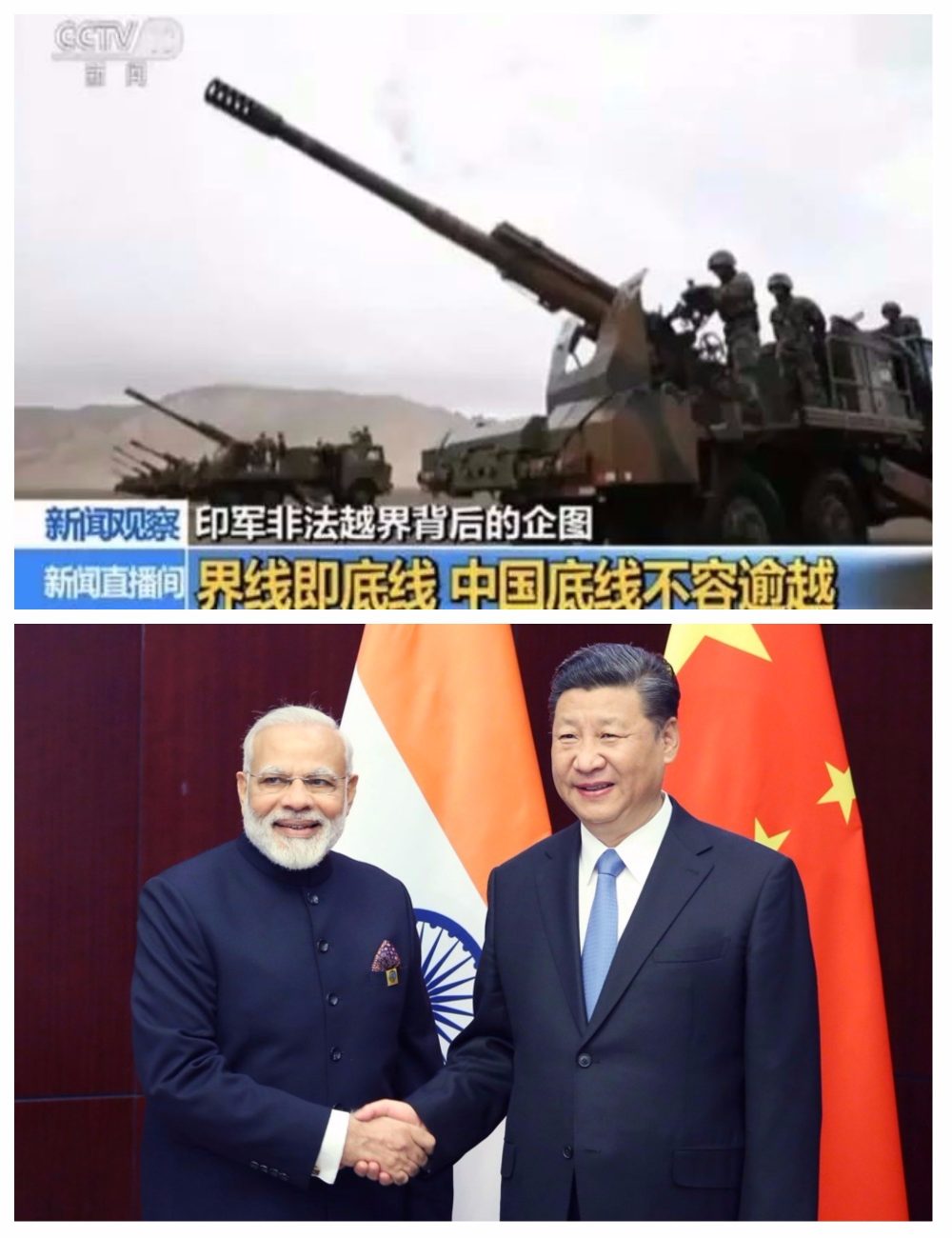

“China and India could really go to war,” I said to myself when rolling down the comment area of a Chinese news site. “Group Fight between Indian and Chinese Troops, Indians Thought They Won!” the title of the article provocatively claimed, referring to the conflict between Chinese and Indian troops, in which both sides threw stones towards each other. From what I observed from the comments, people were agitated by the piquant nationalism the news evoked. And many of them demanded war.

This was not news. On June 18, 2017, a small detachment of Indian troops marched into Doklam, in protest of China’s road construction, which started there two days before. Since then, the conflict waxed for two months. For the first time since the 1962 Sino-Indian war, no one was certain about peace anymore.

However, the built tension evaporated only two weeks later, alone with the opening of the BRICS summit. Indian Prime Minister Modi appeared on the summit and proclaimed, “China should not view India as a competitor but as a friend.” Was this change of attitude somehow related to the summit?

If so, what’s so important about the BRICS?

The “Gold Bricks”

In 2001, a Goldman Sachs economist used the abbreviation “BRIC” to put together the four contemporary economic superstars: Brazil, Russia, India and China. In 2009, China used this idea to form the BRIC summit for those four nations. Based on the pronunciation of the “BRIC” acronym, China aptly titled the event the “Gold Brick” summit. As the name suggests, China touted the BRICS summit as explicitly economics-focused.

At the time of its foundation, the summit’s economic purpose seemed feasible. The first BRICS summit (then “BRIC,” since South Africa had not yet joined as a member and was not involved at the time) was held in Yekaterinburg, Russia in 2009, parallel to the 9th meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). In the context of the 2008 global financial crisis of 2008, the first summit focused on the construction of a multilateral monetary system. If the SCO can be viewed as Central Asia’s buffer for Russia and China to act against NATO, then the BRICS would be an emerging “Eastern counterpart” of the Bretton Wood system, the perished global financial system led by the U.S. since the WWII, a new form of economic alliance. In this sense, BRICS seems to be an economic alliance by design.

A Waning Alliance?

However, the economic goal of the summit, even if it was not a façade, was unsuccessful regardless. As Goldman Sachs, the conceptual mastermind behind “BRICS,” withdrew its mutual funding for the summit and filed a grim report on the BRICS’s poor economic performance, the “Gold Bricks” seem to be fading away.

Data shows that economic ties between the five countries have never been very strong, and the desired financial system they have tried to establish has been proved near-unattainable. Until 2017, foreign investments toward each other between the five countries has accounted for less than 6% percent of their total investments. In the financial sphere, three member states of the BRICS—China, Russia, and India—have feeble mutual fund markets with a share of GDP lower than 5% (Brazil and South Africa both have mutual fund markets occupying more than 20% of their GDPs). Without robust financial intermediaries, there is little financial hope for the financial goal of the BRICS.

For no good reason could economic alliance be the binding force that holds the five counties together; that is, not an economic one.

The New Game

Through the recent 2017 summit, India and China have given the summit new meanings.

The summit will now play a more political than economic role, however. While China will try use it to bring together its economic allies, India will use it as leverage to resolve regional political conflicts. Two relative events that happened during the summit deserve close attention: the summit’s new stance on terrorism and the China’s “BRICS Plus” plan.

The Xiamen Declaration that was put forward by leaders after the summit has some peculiarities. The declaration, for the first time in the summit, specifies Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) as terrorist groups. These two groups are known for supporting Pakistan’s claim over Kashmir against India, and the Pakistani government is speculated to have been secretly supporting them. China and Russia have a permanent veto in the U.N. Security Council to block sanctions on these groups in order to stand in line with Pakistan. Just in early August, China blocked a U.N. resolution to place a terror tag on Masood Azhar, chief of the JeM. This sudden change of attitude, then, is no coincidence. To make sense of China’s compromise, the military standoff mentioned in the beginning of the article should be considered, for it is hard not to draw connection between the two events. If China did indeed make the concession for India’s attendance at the summit (it would not look good if India did not show up), India has made a political victory. Terrorism has been a source of both instability and economic costs for India . With China finally partially dropping support for Pakistan, India can finally expect a boost in investor and domestic confidence that it has been longing for.

On the other hand, China has a more global plan for the BRICS. Since April, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi has been emphasizing China’s “BRICS Plus” plan, a policy to expand involvement of non-BRICS countries. During the 2017 summit, China invited five non-BRICS countries to Xiamen. Although there were past instances of of host nations inviting neighboring countries, it was more of a decorum, like inviting neighborhood children to the party. However, China placed Egypt, Kenya and Mexico on its guest list. “Our practice [of “BRICS Plus”] is little bit different, we are not just inviting countries in our neighborhood, but also countries from all around the world that are interested in BRICS mechanism,” foreign minister Wang said, responding to the press. This “BRICS Plus” policy will likely become a political parallel of China’s OBOR initiative. The former would provide the latter political mediation in South Asia by integrating more participants from all parts of the world and creating more economic bonds. On the other hand, China’s global economic plans will be able to dilute the regional political tensions that the BRICS currently face. However, Indian is fears of losing political leverage, it vehemently opposed the “BRICS Plus” during the summit, foreclosing the plan’s future direction for now. There is now a new question for the BRICS’ political role in international affairs: to stay regional or to go global? The answer lies in China and India’s future actions and aspirations.

Featured Image Source: Xinhua, CCTV

Be First to Comment