In recent years, Berkeley students have been able to count among their numerous traditions a new and exciting community event: anticipating, protesting, and somehow finding a way to survive tuition hikes. Forget the bonfire and night rallies, the University of California is playing a new game, although it’s decidedly more blue and deals almost exclusively with gold (but not in the good way).

As easy as it is to boil down the school’s budget pitfalls to a fence or a few RSF classes, like most problems in politics, the discrepancies are deeper, older and more complex than most would like to admit. We are no longer talking about a few thousand dollars or even millions; this decadal problem deals in the billions range.

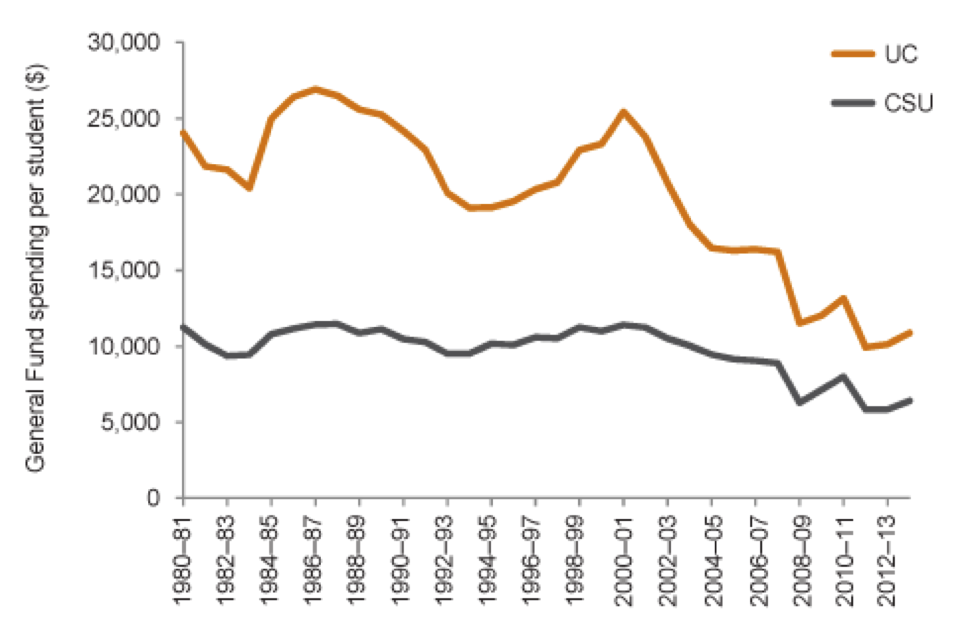

Talk to any Cal alum from the 50s to the 80s and they’ll immediately harken back to the good old days of $50 tuition. Since the 1990s, however, the state of California has slashed its funding of UC from $18,820 per student to $7,780. This slash, like most ideas in politics, was part rational response and part failed arithmetic by the state. The UC system has been funded, in large part, by state tax dollars derived almost exclusively from property taxes (which does not account for research grants or private donations). However, in 1978, California passed Proposition 13, a now ridiculed but once necessary piece of tax legislation which reworked the state tax policy. Prop 13 found its inception in legitimate concerns of California taxpayers, who, prior to 1978, paid some of the highest property taxes in the nation. These high taxes, along with the wonderfully named “Stagflation” of the 70s, meant many Californians were at risk of losing their homes. Wages just couldn’t keep up with rising costs, nor could they compensate for inflation; and who says history won’t repeat itself? Pioneered by conservative brain trusts Paul Gann and Howard Jarvis, the California Republican Party successfully created a policy that was approved by 64% of voters. Proposition 17 capped income to levels relative to the era one purchased their homes. In other words, the value of a home the year it was bought determines the tax. Additionally, once assessed, the tax rate is prohibited from increasing at anything more than 2% per year. If you wondered how so many old hippies could smoke quarter pounds by the day AND afford their Grizzly Peak home, you weren’t imagining it: as far as their property value is concerned, they still live in the 70s.

Prop 13 has failed to adapt past the 1980s. California has the 18th lowest property tax level, which in recent years had not provided enough revenue to fund the state’s large university system. For America’s most populous state, funding a world-renowned university system with no less than nine campuses-not even counting state universities-can get expensive. Yet, the state has both slashed its funding to the UC system while the system itself has grown in size. Look no further than last year’s state budget proposal, which mandated an additional 5,000 students admitted to UC while appropriating only half the money needed to satisfy the new expenses. The fact of the matter is, neither state revenue nor state appropriations have kept up with the University’s growth.

While Proposition 13 helped to ease pressure on small businesses and California homeowners, it also acts as a massive tax cut to some of the largest businesses in California. Disneyland, for example, has not had its expansive 85-acre park in Orange County revalued since 1975, meaning Orange County alone is missing more than $4 million in tax revenue by taxing the land according to decades-old land valuations. Likewise, large businesses who want to avoid purchasing land-which would trigger updated land values and this higher taxes-simply transfer parcels of land back and forth in order to avoid legitimate sales, exploiting one of the 13s numerous loopholes. Prop 13, originally a tool to protect the everyday Californian has unwittingly tethered revenue to a legislative stake. Prop 13 was meant to protect grandma and the ranch, not theme parks and oil fields.

Compounding upon the fiscal fiasco was the economic crash of 2008, as well as long list of poorly timed expenses, which have brought financial hardship to the entire UC system, with Berkeley being hit especially hard. All the while though, UC expanded. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, “Between 2007–08 and 2012–13, state appropriations to UC and CSU fell by $2.0 billion (from $6.3 billion to $4.3 billion in 2013–14 dollars) or more than 30 percent, even as enrollment has increased.” Spending millions on a new stadium and having to perform mandatory retrofitting on a number of other campus buildings didn’t help either.

As costs increased and bills became due, the UC Regents began to backfill the school’s empty coffers by-like a bad first date-passing the check onto students. “Tuition” is now the largest single source of operating funds for the University. Gone are the days of $500 “educational expenses,” the term used for well over 100 years, a reflection of the now-exacerbated costs of higher education. This year’s 6% increase in tuition is nothing new, and for most students, nothing unexpected.

There is, however, a budding hope; amongst both students and politicians pressure to reform 13 is growing. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, over 700 of the state’s elected officials and more than half the state’s voters agree that 13 needs to change. Students at UCLA as well as the greater University of California Students Association (UCSA) have begun their own lobbying group to put pressure on UC President Napolitano, Governor Brown and the California State Legislature to modify Proposition 13 to increase funding. The organization, Fund The UC, has groups on all nine campuses. This is a good start, as groups like Fund the UC targeting lawmakers reluctant to allocate money to the UC system and changing some of the sections of prop 13 as an effort to look for real systemic change as opposed to short term patch ups. Additionally, the ASUC is putting pressure on the state government with its own student lobby conference in late March, encouraging a diverse conglomerate of students to make the trek up to Sacramento and lobby their state representatives about issues that affect the diverse UC student body. Recently, both State Senators Nancy Skinner and Holly Mitchell have backed student led propositions to reform the commercial and industrial loopholes of Prop 13. While there are signs of progress, and the backing for Proposition 13 reform may be numerically strong, getting it past the multiple business entities who lobby in favor of the status quo will be no small task.

Each year, with nervous anticipation college students wonder how they’ll balance that finance tab on CalCentral and if, next time they log on, it will even be the same number. If anything can be done in the short term, it can be to educate ourselves as students. We must realize that this issue is not normal and not something intrinsic to the history of the University of California. Most importantly, we must realize the magnitude and scope of our predicament. It’s not about a few overpaid administrators or a secret hatch being built into an office, it’s a systematic starving of a once well-fed University.

Featured Image Source: Tonya Nguyen, Berkeley Political Review

Be First to Comment