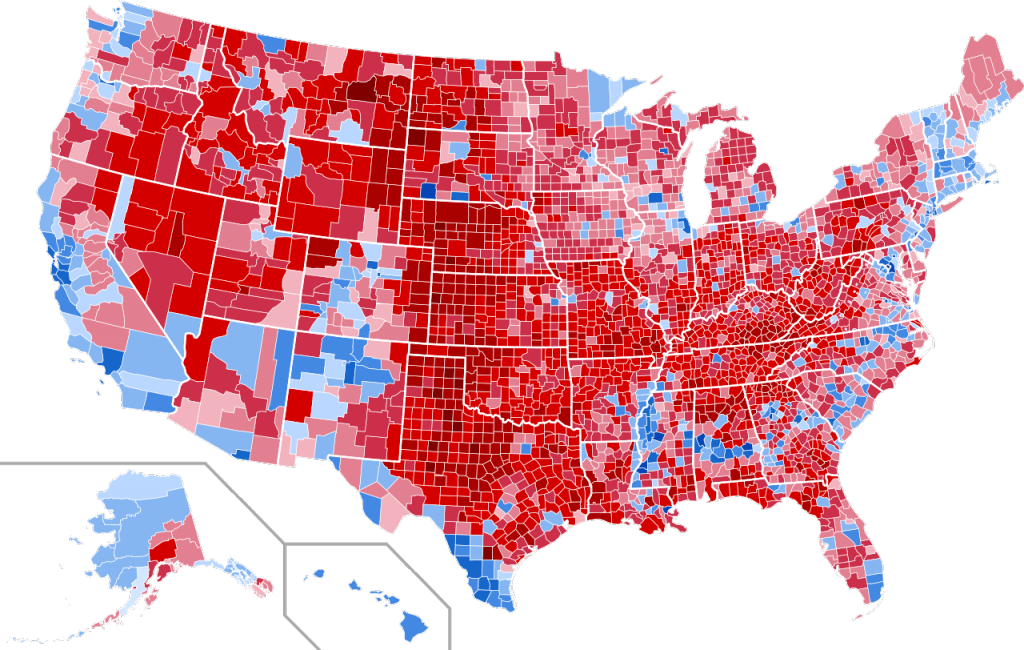

In America, we are made to believe that politics should be discussed in terms of states. Blue states and red states dominate our electoral maps, our Congress is filled with state representatives, and state elections are second only to national elections in terms of relevance to the average American. But states and state borders are generally arbitrary divisions of land, with no apparent rhyme or reason to their size or placement. Why are Texas and Rhode Island, the former being over 200 times larger than the latter, afforded the same representation in the Senate? Why are some states, like Colorado and Wyoming, rectangular, while others, like West Virginia and Tennessee, have their borders defined by landmarks? And why have urban megalopolises like Los Angeles and the Bay Area been randomly lumped together with rural expanses such as the Central Valley in states like California, made to act as a singular political unit? Ultimately, one begins to wonder – why do we even have states in the first place, and why are they so central in our discussions of politics?

Of course, states were natural divisions in the early years of America, as the thirteen colonies banded together against Great Britain as “united states” rather than a contiguous nation. As the United States grew, new territorial claims were slowly organized into manageable chunks, which were admitted as new states. However, the methodology for determining the borders of these states varied depending on the location, knowledge of the region, and political climate. Inaccurate surveys led to conflicting borders, states such as Maine were created to maintain the balance of free and slave states, and a brief war was even fought between Michigan and Ohio over possession of the Toledo Strip, an area of economic significance. But as America spread across the map, states proved to be useful ways to consolidate communities into political units. Settlers in regions such as Texas sought admission to the United States as new states in order to preserve their self-governance while ensuring protection from Mexico and assumption of their debts. But now that our national borders have been set, and now that centuries have passed since the age of colonies, it is prudent to reexamine our state system to determine whether its benefits truly outweigh its costs.

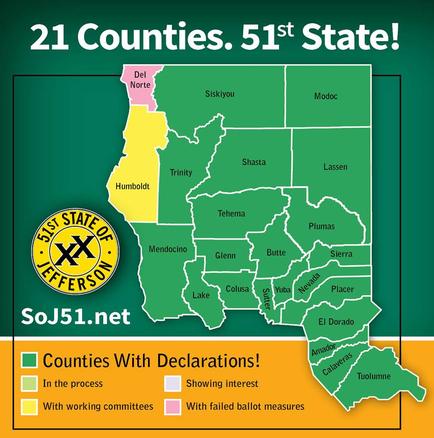

Discussing politics in terms of states has proven to be a reductionist way of considering our complex political atmosphere. Take, for example, California. Our state is an established Democratic stronghold, and a solidly “blue” state – Hillary Clinton received nearly twice as many votes as Donald Trump here, and the Democratic Party has a supermajority in both the state Assembly and Senate. But to dismiss California as a uniformly blue state would be to ignore the sizable conservative and Republican movements that exist outside of the major cities. Northern California, for example, is in reality conservative but drowned out by the rest of the state – leading 21 counties in the region to declare their desire to split from California and form the State of Jefferson. Nonetheless, California is portrayed in political media as the progressive antipode to the Trump White House, ignoring and erasing the efforts of the state’s conservatives.

Additionally, despite the rhetoric surrounding “state’s rights”, state legislatures provide an additional barrier in our democracy between the people and their governments. In American democracy, one has two direct methods of bringing about political change – voting and becoming a politician. Activism and protest, and likewise lobbying and funding, are also valid methods of political action, of course, but they ultimately are done to impact the decisions of voters and politicians. But on the state level – much like on the federal level – singular votes have vanishingly small impacts on election results. And in most states, especially the more populous ones, being elected to state office is extremely difficult for the average person. Even successful protest movements are generally unfeasible for any single person to start. In short, any single person’s impact on even state politics is negligible at best, and thus they are fundamentally separated from a government which supposedly represents them better than the federal government. The structure of the state system simply prevents members of the population from reliably effecting change. However, the same is generally not the case for local governments. On the local level, singular voters or small groups of people can reliably impact election results. Additionally, being elected to local office is far more achievable for the average person than doing the same on the state level. And the functions of the state governments could reliably be absorbed by the federal and local governments. Nevertheless, this middle level of governance persists, preventing the people from having greater control over their politics.

Although people may not be able to reliably effect political change singlehandedly, groups have more power. However, the state system also allows demographic inequities in our voting system to remain unchecked. One such inequity – the divide between urban and rural voters – is addressed by the Electoral College, which in theory prevents voters in metropolitan areas, who may normally have a popular majority, from being the sole drivers of national policy. And while many have lamented the perceived unfairness of this system, in actuality the Electoral College was proven to be more relevant than ever in the 2016 election when it exposed the Democratic abandonment of the white working class which led to the unexpected popularity of Donald Trump as an anti-establishment candidate in the first place. However, the Electoral College is an inefficient way to address issues of urban-rural demographics. Take, for example, the overrepresentation of voters in Wyoming as compared to voters in California. Does this mean that Wyoming ruralites should have greater influence than rural voters in California? Clearly, the Electoral College is not an efficient method of preserving equity between urban and rural voices. Additionally, the Electoral College only addresses one inequity of demographics when in reality countless others exist. However, any attempt to address these inequities which is based on the state system will be limited by the fundamental randomness of state borders – and so at best any such solution will be an approximation of a better, more efficient system. The arbitrary divisions states impose on American politics ultimately prevent more equitable and democratic systems from taking hold.

In all fairness, state governments are useful in applying large-scale policies that would usually be the purview of the federal government on a more local level. States are a very successful system when it comes to political experimentation – take the topical example of legalizing recreational marijuana. Colorado, by being among the first states to legalize pot, allowed other states to see how such a system could be put into practice, and helped the movement gain traction in nearby states. Other issues, such as legalizing gay marriage, demonstrate how successful political experimentation on the state level can lead to national political change. Equally important is the role of states in shielding their citizens from the federal government. This feature has been magnified in the early days of the Trump administration – progressive states such as Hawaii have challenged White House policies in court, while other states like California have pursued infrastructure projects and single-payer healthcare bills while being disavowed by the federal government.

Nonetheless, the state system is not the best method for bringing politics closer to the people. States are a poor approximation for localized governance – an unnecessary middle level of government between the federal and local levels. Ultimately, for nearly all problems of governance not involving collective action, dispute resolution, protection of human rights, or geopolitics, local and community governments are both sufficient and preferable to state-level legislation.

Indeed, many of the best features of the state system could be accentuated by eliminating state governments and replacing them with highly localized community governments. Local governments are infinitely more flexible and responsive to the people they govern than state governments, especially in large states like California. Currently, the only drawback of local government is the lack of power it holds over policy decisions. But when the state system is eliminated, local governments could assume a wide range of powers which allow the citizens they represent to truly have a choice in how they are governed. Progressive cities like Berkeley could experiment with far-left policies without fear of rebuke from the state or federal governments; strongly Republican areas could implement tax cuts and social policies that normally would be neutered on the higher levels; communities and cities could be allowed to fail, such that the best policies were exposed through a sort of political natural selection; and the desires for political experimentation and against tyranny of the majority could be brought to fruition more efficiently and equitably.

Of course, America would quickly fall apart as a Union without any higher level of government. A federal government has always been necessary and desirable. Nonetheless, to keep the focus on the local level of governance, the federal government should be limited to governing only what is absolutely necessary. The focus should not be on trying to control every aspect of the nation, but rather to see how much can be ignored and left to the jurisdiction of local communities without bringing about the nation’s collapse. However, there are some clear problems which should be the concern of the federal government – most obviously, geopolitics and dispute resolution between communities. Additionally, the federal government should at least ensure the negative rights of its citizens. (Negative rights are those which cannot be given by a government, only taken away, such as freedom of speech.) And left to their own devices, community governments will not efficiently manage collective action problems or tragedies of the commons, meaning solutions to these should be sought through the federal government as well.

But there is a hidden beauty to a local-government model when coupled with absolute freedom of movement. These two principles, brought together, would create a free market of governance throughout the nation. This enables individuals to decide how their government is run to an even greater extent – they can choose to either effect change through a democracy strengthened by its proximity to the people, or move to a different community with a government more in line with their beliefs. Of course, freedom of movement would have to be actively defended rather than passively ensured by the federal government. All individuals, be they poor or rich, young or old, must be able to start life anew in a different community without incurring great cost, lest the free market of governance be a privilege afforded only to those capable of easily uprooting themselves and moving elsewhere. But if government is as local as possible, and if freedom of movement is guaranteed for all, successful models of governance will emerge and be rewarded by larger tax bases, while unsuccessful models of governance will die out and be replaced by better ones as their population dwindles. Niche systems of government will also be able to succeed, as those who desire them will be able to seek them out or establish them in failing areas if they do not already exist.

It goes without saying that this would be a radical shift in how the country is governed, and may not be a realistic model to implement fully. Perhaps this cure to the state system would end up being worse than the original ailment. The transitory period alone would be a massive imbroglio, as local governments rush to take advantage of their newfound powers and the infrastructure required to guarantee freedom of movement is put into place. However, it is important to recognize the symptoms that this model attempts to remedy. The political gridlock we are experiencing on the federal level could be alleviated if people felt that they were adequately represented on the state and local levels, as this would reduce the severity of federal decisions. Democracy, in general, is restored when people can make an impact on their governments, and allowing for increased freedom of movement would ensure that those in failing communities can be guaranteed life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness elsewhere. And all of the benefits of eliminating the state system are only accentuated by the cost savings of one less level of bureaucracy. States may have dominated discussions of America for the last few centuries, but that does not mean our country cannot succeed without them.

Featured Image Source: Wikipedia

2 Comments