Written November 21, 2016.

As Governor Jerry Brown trekked on a dry, brown meadow nearly 7,000 feet above sea level, something was wrong. The date, April 1st, 2015, seemed appropriate: it was almost like a joke gone wrong; where there had once been a copious amount of snow covering the ground, there was not one ounce of moisture. In fact, for the first time since the annual snowpack surveys started in 1942, there was no snow to be measured at all. “We’re standing on dry grass, and we should be standing in five feet in snow. We’re in a historic drought, and that demands unprecedented action,” Brown declared.

And with unprecedented action is exactly how Brown responded. Later that day, Brown issued Executive Order B-29-15, which aimed to achieve a 25% reduction in urban water use. It was an aggressive, bold step towards mitigating the effects of the drought, but it had its shortcomings. Many argued that the agricultural industry was given a free pass and could be doing much more to conserve water. Farmers were not affected by the cuts; the mandate focused on domestic water use, not agricultural water use. Alastair Iles, a professor at UC Berkeley who specializes in environmental law and policy, remarks, “Many were very surprised that Governor Brown exempted the agricultural industry from the mandatory cuts…. Even though they consume 70-80% of the water, they don’t produce the same proportion of economic benefits for the state.” In fact, agriculture only generates 2% of California’s total gross domestic product.

Despite the agriculture loophole, there was a significant impact from the executive order, which placed the burden on ordinary citizens to save water. Californians cumulatively cut water use by 23.9% compared to 2013 levels. Communities around the state were forced to reduce water usage between 8 to 36 percent, threatened with the consequence of state fines if they failed to comply. In order to meet the goals, unique solutions were crafted to reduce water use. Watering schedules were implemented, with residents only allowed to water their lawns on certain days and only during specific hours. Subsidies were offered to get rid of lawns altogether and to replace them with drought-tolerant plants. Restaurants were legally prohibited from offering water; instead, customers had to ask for water. As prices rose for excessive water use, residents were encouraged to save water by buying more efficient appliances, with rebates provided in many cities.

The restrictions significantly helped water conservation efforts, which is why many were confused when only a year after its implementation, the State Water Resources Board decided to end mandatory restrictions and to give local municipalities discretion over conservation efforts. Many experts, including Professor Iles, believed that the state was forced to retract statewide regulations because of legal challenges; Riverside sued the state, arguing that the cuts were too severe, and in a separate case, an appeals court overruled tiered water rates in Orange County, which was a key tool used to discourage excessive water use in two-thirds of the state.

Devolving power back to the local water districts, Professor Iles argues, will only lead to increased water consumption, because in many agricultural zones, the industry wields immense control over the districts. As a result, these water districts may choose to loosen water restrictions in order to benefit farms. Urban areas haven’t fared much better. Some kept water restrictions stringent; the Santa Clara Water Valley District, which originally had a mandatory cut of 30%, now has a goal of reducing 20% of water use. Others, such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and the Coachella Valley Water District, have slashed mandatory cuts to 0%. Water providers emphasize that they set their targets at zero only because they feel that the area is well-prepared to handle long term water shortages. Tim Quinn, executive director of the Association of California Water Agencies, stated that, “Calculating a zero… means you’re drought-prepared because of the action you and your community has taken. That’s a good thing.” Across the state, results have been mixed. From June to September, although Californians are still decreasing water use, conservation rates have continued to drop. Because of the localized control, some areas have fared much worse than others: Malibu saved 20.4% of its water in August 2015, but in August 2016, the rate dipped to 7.9%. Similarly, in the aforementioned Coachella Valley, the reduction in September 2016 was a measly 4.3%. The average person in Malibu and Coachella now uses over 300 gallons of water per day. In comparison, the average person uses between 80 to 100 gallons.

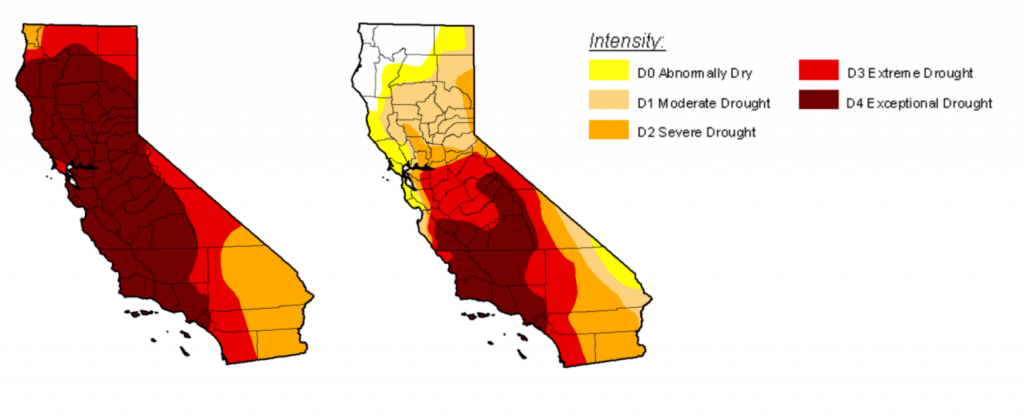

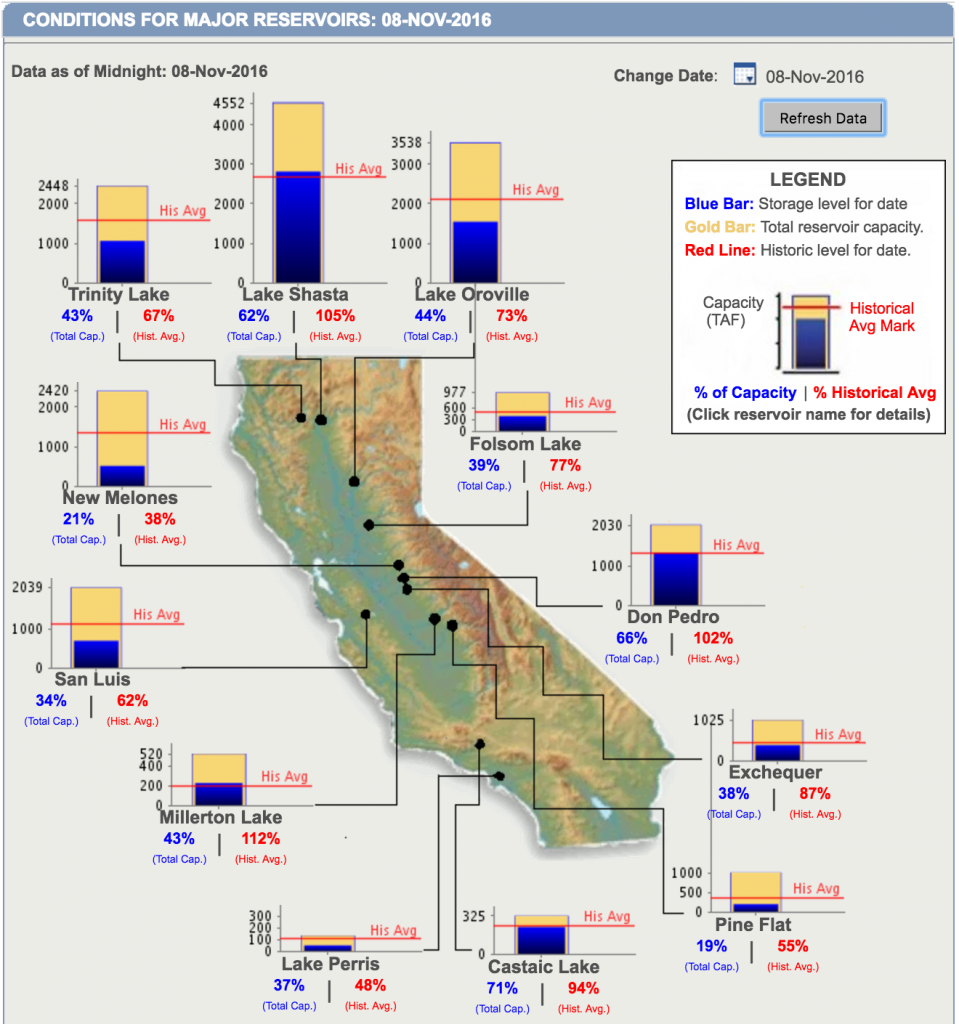

But is all this saving necessary? Critics of strict water regulations argue that the drought is virtually over. Professor Iles does believe that the claims in 2014 that California would run out of water in a year were exaggerated; however, he warns that California is still not out of the woods, commenting, “The snowfall might not be as good this winter. If so, we will be back in deeper drought. So much depends on the level of snow and the melt at the end of winter.” A particularly wet October has helped fill reservoirs, particularly in the northern part of the state. In addition, drought levels are significantly better today than they were in 2014. That being said, 62% of the state is still in a severe state of drought, and nine out of twelve of the state’s main reservoirs are below average historical water levels. Furthermore, the three reservoirs that are above historical averages are only barely so. Even more sobering, a study from the Department of Water Resources projected that the Sierra Nevada snowpack will “experience a 25 to 40 percent reduction from its historic average by 2050.” This could be devastating for the state, as California gets 30% of its water from the snowpack. Such a large loss coupled with an increasing population could lead to disastrous consequences if long-term plans are not made.

One proposed solution is increasing the use of groundwater. A recent study has estimated that the Central Valley aquifers may hold three to four times more freshwater than previously thought. Robert Jackson, co-author of the study and an earth scientist at Stanford University, said “The good news is that water is more abundant than we expected.” There is a catch, however: 35% of the water could be already contaminated by oil and gas development, and most of the water is too deep to feasibly extract. Excessive groundwater extraction also has devastating consequences. The water table has sunk 50 feet below normal levels over the last few years, which has caused the land to subside at a rate of 2 inches a month in extreme cases. The deeper the water table sinks, the more expensive water becomes to extract. Even when the water table is restored to normal levels, permanent damage has already been done; aquifers are able to store less water overall due to soil compaction when too much water has been drained.

So how can California effectively deal with the drought? Professor Iles points to his native country, Australia, for inspiration. From 1997–2010, Australia experienced the worst drought in its history. Australia cut average water consumption from 65 gallons per person per day to only 39 gallons, a 60% reduction over the course of 10 years. In comparison, the average Southern Californian uses 104 gallons per day, already 60% higher than Australians before they started emphasizing conservation. Some tactics are similar to ones used in California: rebates on water-efficient appliances like washing machines, which some local California counties still offer; and training garden center employees to help residents install drought-resistant plants, comparable to California’s rebates for homeowners willing to replace lawns with drought-resistant plants. However, Australia had even more extreme programs, such as distributing free water-saving equipment, an aggressive advertising campaign that made water conservation popular for all types of people and industries, and even giving out water bills that compared customer’s’ water use to their neighbors. In addition to the stricter regulations, Professor Iles believes that part of the reason Australia has had more success in tackling the drought than California is the difference in cultural attitudes. “[The regulations] were not so popular of course, but the level of awareness of the drought and its harms on the Australian countryside was very high so people became more willing to accept these limits,” Professor Iles noted. “In California, I suspect that the majority of people do not really grasp that there is a drought underway.” Solving California’s water shortage won’t be simple, but one thing is clear: California must attack the drought from all sides—farmers, residents, and the entire water supply system itself—if the state wants to gain meaningful progress.

Featured Image Source: Jae C. Hong

Be First to Comment