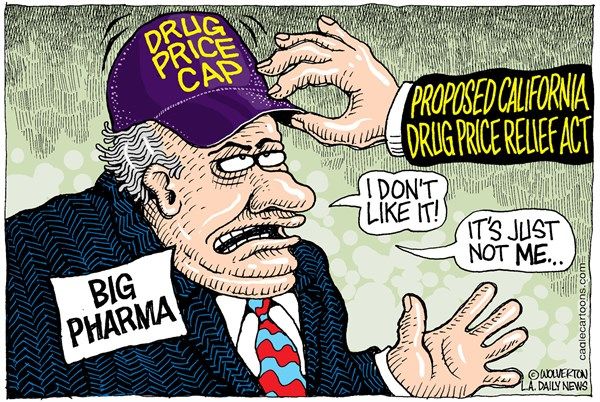

Government regulation is at it again. This time, it’s going after Big Pharma. California is the latest state to propose a ballot measure that, if passed, would set a price ceiling on prescription drugs paid for by state agencies.

The California Drug Price Relief Initiative, proposed by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, a Los Angeles-based patient advocacy group, will appear on the November 2016 ballot and already faces a major uphill battle. The measure has attracted national attention, which is especially fortuitous given that many young people, especially those familiar with VICE News and Twitter, have become familiar with the exploits of the pharmaceutical industry through Turing Pharmaceutical boss Martin Shkreli, aka ‘Pharma Bro’ and his now-infamous markup of the AIDS treatment drug Daraprim.

Aside from Pharmo Bro, there are immense, multinational pharmaceutical firms similarly marking up the prices of prescription drugs but with virtually no media coverage. And often, consumers are finding that the same over-the-counter prescription drug that they paid one price for going for a higher price the next day.

The initiative tackles the complex, multifaceted, and financially indecipherable mess that is prescription drug pricing. The Drug Price Relief Initiative proposes pegging the price that California state medical programs can pay for prescription drugs to the price set for said drugs by the United States Department of Veteran Affairs, the primary authority on the pricing of prescription drugs at the federal level. An expedient explanation of the measure is to describe it as a law that could effectively increase the California government’s subsidy over prescription drug prices.

But to accept the above assessment is to willingly extend the national healthcare debate into medicine pricing, thereby adding another dimension to a conflict that, at least in the meantime, has no foreseeable end in sight.

Proponents of the initiative are faithful that government can once again be the solution to the abuses perpetrated by the pharmaceutical industry. By claiming that the profits of pharmaceutical sector outnumber those of the investment banking sector and citing the use of profits to compensate high-level executives, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation presents a narrative of throngs of frustrated and increasingly compromised consumers pitted against the forces of pharmaceutical greed.

These findings, though debatable, however, are not entirely unfounded. It is true that the private sector is heavily invested in the fight over the bill, including some of the largest brand names in the pharmaceutical industry, including Pfizer, Inc. and Johnson & Johnson, and that their profits are massive—Pfizer alone netted a profit of $13.8 billion in 2015.

But producing profits is not, nor can it be considered as, a crime for private sector businesses. Yet, perhaps because the production of prescription drugs impacts human lives in a more direct and potent way, there is greater scrutiny on the producers of potentially life-saving medicine to be less concerned with profits than with health needs of consumers who need their products. Therein lies the heart of the conflict, because proponents of the initiative would argue that the root of the problem is pharmaceutical companies treating medicine and prescription drugs as a product to be sold at prices

that don’t help consumers.

As compelling a cause it may be, it’s also an incredibly complex one to take up. There are a myriad of questions and concerns that advocates of drug price stabilization must consider before formalizing a plan of action. However, California’s Drug Price initiative may not be the right response. It’s an idealistic measure, sure, but there is too much of it under question for it to serve as a valid first example for future measures of its kind. For one, its financial implications are still unclear, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

In the 50-day period that is required of the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to review and prepare a financial summary of the impacts of initiatives, the LAO was “unable to come up with a reasonable estimate of the measure’s potential fiscal impact on state costs for prescribed drugs.” California voters may now be wary going into the polls in November, knowing that a price tag is not attached to a measure where there should be one.

Taxpayers ought to know the price they have to pay—quite literally—to implement such a bold and far-reaching law. The assumption, which goes without saying, is that Californians may face a tax increase, the magnitude of which is yet unknown. Which begs the question: who benefits from the drug price relief?

Some may answer that the entire population of Californians who buy prescription drugs do.

Not quite so.

Rather, it’s critical to read the text of the initiative, in which it is stated that the price ceiling applies to “all programs where the State of California or any state administrative agency or other state entity is the ultimate payer for the drug.” Take that a step further and we can conclude that people covered by state-subsidized health care programs are the primary beneficiaries of this law.

According to an interview by the San Jose Mercury News, Michael Weinstein of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation quantified the beneficiaries to be the 2.2 million Californians covered by Medi-Cal’s outpatient program, as well as nearly 110,000 prison inmates and another 2.5 million state employees and public school teachers covered by CalPERS and CalSTRS, respectively.

Viewed from another angle, this bill does not apply to the 14 million Californians covered through private insurers, leading to a possible disagreement among voters about who would pay and who would reap the benefits.

The success of this bill in November hinges on the willingness of California voters, many of whom are not covered by state-subsidized health care programs and therefore not eligible for the price ceiling, to accept the possibility of higher taxes in order to allow for fellow voters, not themselves, to benefit from a large-scale drug price subsidy.

Nowhere is the fight over this bill more bitter and more telling than in the realm of campaign finance. The fight over California’s drug price initiative is already considered one of the most expensive of the 2015-2016 election year. But it is no way competitive—opposition funding outranks proponent funding nearly 10 to 1; nearly $53 million have already been raised to defeat the initiative, and much of it comes from the largest and most profitable pharmaceutical firms in the United States.

Meanwhile, fundraising in favor of the measure stands at $5 million and does not have nearly the same funding from the private sector as its opposition. Perhaps that is favorable for those who support the initiative, in a way. By deterring, maybe even rejecting, donations from private sector corporations, the sponsors of the bill refuse to tie themselves to interests that could one day cash in on their donations and could thereby assume a form of moral and ideological purity that can prove to be political capital by appealing to supportive voters.

But the pharmaceutical industry could either be the bill’s biggest supporter, or its worst enemy. In the case of the California drug price initiative, it’s the latter. Asking the private sector to share a burden of the cost may seem like a reasonable request from the point of view of the people supporting the bill, but in reality, is not that simple. For an industry that rakes in multi-billions of dollars in revenue each year, any request to foot a bill is the equivalent of interrupting momentum.

The pharmaceutical industry justifies their opposition to the initiative on the grounds that pegging the price would deter medical innovation and limit the choices of prescription drugs for consumers. Whether these justifications are strong enough to compel voters is debatable. Rather, in this case, the money might be the key factor. For that, there is precedent; for each ballot measure in the 2014 election season, the side that raised more money won. Proposition 45, which was defeated, had the highest opposition versus proponent fundraising difference of $50,018,714, and that figure that is only slightly larger than the $48 million differential of the drug price relief initiative, whose fundraising differential is likely to grow as the election approaches.

Disregarding all the complexity, it’s easy to become embroiled in a debate over the ethical dimensions of the Drug Price Relief Initiative. Progressives—and even some conservatives—may contend that stabilizing the price of prescriptions drugs would protect consumers who are asked to pay more than they can afford to acquire potentially life-saving drugs. That might be true, but it is also worth noting that one weak bill which yields unintended results and public backlash can easily cripple a cause and frighten lawmakers enough to prevent them from enacting similar measures.

This bill is arguably the first of its kind, but if it fails, how will that reflect on the fight for drug price stability? The battle may be good, but is California’s Drug Price Relief bill the right one to set the precedent for the rest of the country? If advocates can answer this question in spite of all of the criticism and opposition the Drug Price Relief Initiative faces, then perhaps there is a chance of victory in November.

Featured image source: L.A. Daily News / Wolverton

Be First to Comment