When Jennifer Machmer was commanding a platoon, she was raped by a soldier serving under her. Unable to bear the strain of the assault trauma on her marriage, Machmer turned to the chaplain of her unit for emotional comfort. While she attempted to confide in him, the chaplain took advantage of her vulnerability and sexually assaulted her again. Machmer said nothing. She attempted to move past these two incidences, until she was raped a third time by a sergeant in 2003. The final rape was the only one that she reported. Jennifer’s story is not an uncommon one. According to a 1995 study conducted by the Department of Defense, about 78% of women and 38% of men experience sexual harassment during their service, and 6% of women and 1% of men have been victims of completed or attempted sexual assault. These numbers are not perfect, given the difficulty in collecting such data, but they are the best estimates that the U.S. government has. Sexual assault may be common in the military, but reporting it is not. In 2014, only 25% of sexual assault victims formally reported the incident to their superior. Few soldiers feel comfortable reporting sexual assault as a result of major cultural and structural issues that persist within the military.

There are elements of military culture that make it socially difficult for victims of sexual assault to report. One of the biggest issues is the chain of command. According to a 2003 report from the American Journal of Internal Medicine, “one fourth of victims indicated they did not file a report because the rapist was the ranking officer. One third did not report rape because the rapist was a friend of the ranking officer.” If the person you are supposed to report to committed the crime against you, it defeats the purpose of reporting—they clearly are not going to take action against themselves. There is no other external method of reporting rape in the military, meaning that people have to go through the commanding officer or not report at all. When rapes are committed by these individuals, there is very little chance that action will be taken, which makes victims much less likely to report.

Another cultural deterrent against reporting is the fear of personal or professional retribution. 62% of victims who reported their rape faced retribution after reporting. Jessica Hinves was among this group. After she was raped, she became a social outcast. She felt like “a cancer” and was considered to be “a liability.” Her commanding officer said that he could not guarantee her safety. This sort of reaction is not uncommon in these situations. Victims of sexual assault are often accused of lying about what happened to them and of hurting the cohesion of the unit. This victim-blaming mindset often results in professional retribution. Jessica Hives was eventually forcibly discharged with a diagnosis of PTSD. There are countless other men and women who have faced both social and professional retaliation for reporting a crime that was committed against them. It is not uncommon for victims of military rape to be forcibly discharged under the label of PTSD without any further explanation. Though rape can cause enough stress to give a person post-traumatic stress, this diagnosis has become a common trick to remove victims from the military, whether or not they want to leave. The culture of the military is one that tries to erase all symptoms of rape rather than to address it directly.

One fifth of military sexual violence victims do not report because the military environment has taught them to view rape as an expected part of military service.This kind of rape culture often exists in environments where hyper-masculinity is encouraged and often leads to an increase in sexual violence. Essentially, the U.S. military has taken the concept of “boys will be boys” to a whole new level. Obviously, aggression is a necessary part of military culture, given the nature of the work the military does, but when this aggression and need to dominate starts to adversely affect the way soldiers treat their comrades, some sort of change needs to be made. Reducing hypermasculinity and the idea of over the top violence may solve the problem of sexual assault in the military. By emphasizing the idea of controlled force and making it clear that violence is a tool of war and not a way of life, the military may be able to take strides toward fixing this problem.

However, many of the cultural issues in the military are complex and can be very difficult to solve. Structural issues are often more straightforward to identify and change. Instituting structural changes to the military can make it much easier for victims to report. For example, a 2003 report stated that one third of soldiers did not report rape because they do not know how to. By simply informing soldiers of the process of reporting and making that process more accessible, more would be able to take action against their rapists. Over the years, the military has been implementing measures to make it easier for victims to file these reports, and the number of soldiers who fail to report due to an unawareness of how has been on the decline.

The other major structural issue that stops people from reporting is the general lack of accountability for military rape. Only 10 percent of people who are reported are ever brought to trial for rape. This means that 90% of people who are accused of rape never even see a day in court—this means that the military systematically invalidated 90% of military rape victims. Even when a person is brought to trial and convicted of rape, they rarely receive more than a slap on the wrist for a crime that would put a civilian behind bars for years. It is not uncommon for a convicted rapist to face mild punishments like suspension, demotion, or a scolding letter in their file. This lax attitude toward punishing rapists discourages people from reporting because they do not believe action will be taken against their assailant. This system ends up creating the worst of both worlds by encouraging rape, while discouraging reporting.

People like Congresswoman Gillibrand have tried to increase accountability to encourage people to report more often. In 2014, she introduced a measure known as the Chain of Command bill, which would have directed rape cases to an independent military prosecutor rather than the commanding officer. Gillibrand argued that reporting to the commanding officer is illogical because they know both the victim and the rapist, meaning that are likely to have a conflict in interest. She managed to build a bipartisan coalition for this bill, including senators Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, and Barbara Boxer. Despite bipartisan support, the measure still failed to pass. Senators including Lindsey Graham and Mark Kirk felt that the bill would be ineffectual and could be bad for the military chain of command. The Pentagon was not in favor of the measure because they argued that they should control their internal affairs, not an outside agency. Until the Pentagon either accepts the idea of external reform or comes up with effective measures for change, accountability may be difficult to achieve.

While horizon for reform seems bleak, there is still some hope. In recent years, the Pentagon has taken action to try to increase the rate of reporting. According to a report from Frontline, “for the past few years, the Pentagon has launched an extensive, public effort to combat sexual assault. It has set up a special office for victims’ advocates, commissioned reports to study the problem and stepped up training. The efforts have encouraged more victims to speak out.” This shows that an honest effort is being made to combat this issue and so far, it seems to be working. In 2014, the percent of people who reported went up by 50%. In 2012, only 1 in 10 victims reported their rape, but now it is up to 1 in 4. Though we still have a long ways to go before fixing this problem, it is clear that the first steps have been taken.

Military rape is a major issue in this nation. Many aspects of the culture and structure of the military make it very difficult for victims to speak out and report the person who abused them. Fortunately, the Pentagon seems to be committed to combating this issue and has been trying to make our soldiers safe. Eventually, we may live in a world where military rape is an atrocity of the past rather than a current event.

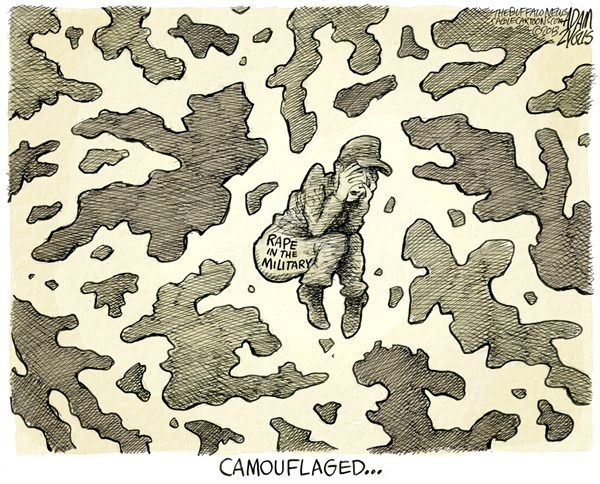

Featured image source: Cagle.com

Be First to Comment